print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 62 mm, width 104 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

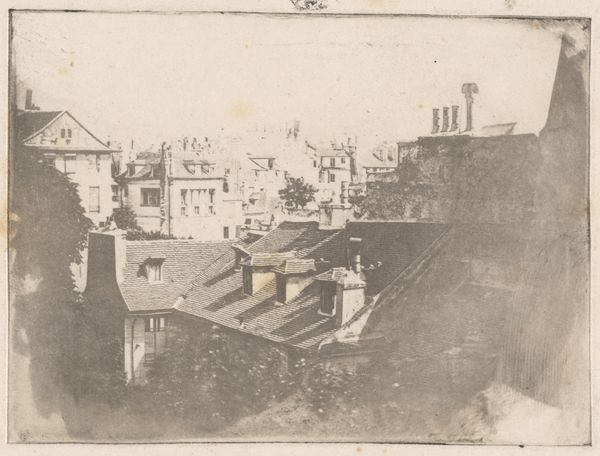

Curator: Oh, this gelatin silver print, titled "Gebouw in Bad Schwalbach, Duitsland," attributed to G. Raidt and likely taken between 1855 and 1885, presents quite a subdued scene. What's your initial take? Editor: My first impression? Ghostly. A whisper of a townscape, like a memory fading at the edges. It feels like looking at a sepia dream. Curator: I see that. The print quality certainly contributes to that. It's interesting how this seemingly objective medium of photography takes on such a subjective, ethereal quality here. Look at the building itself - it commands space in a rather austere way. Editor: Austere, yes, but also somehow inviting. Those repeated window patterns... it speaks to a collective memory, the kind that Carl Jung wrote about. An archetypal European town, solid but somehow light in being. What’s the psychological weight of repetition in architecture like this, I wonder? The windows seem almost like eyes. Curator: I hadn't considered the "eye" motif, but now you mention it, I can see the human-like architectural composition in that perspective. I suppose, traditionally, windows offered safety by granting perspective within a dwelling or architectural compound. Editor: Exactly! In that time the camera, too, was another type of "eye". How else could someone far away see a faraway scene? Beyond realism it's also about extending one's perception. Look at how small people seem by comparison with the building, perhaps suggesting they are dominated by a structure bigger than their own lives. Curator: That brings to mind the socio-economic context, though, right? The architectural scale as an explicit demonstration of economic success and status. Even in what seems like a candid snapshot. Editor: The longer I look, the less "candid" it seems. It feels deliberately composed, staged even. Maybe that is another dimension about realism—to look real enough it needs some work. This artwork embodies both something present, a building, but also some element of the ephemeral past, that once happened but is no longer. It’s an object laden with symbolism about what came before, I feel. Curator: A really intriguing way to conclude. Yes, I think this little print, unassuming as it is, manages to evoke layers of meaning about space, time, and perhaps even the very act of seeing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.