Copyright: Public domain

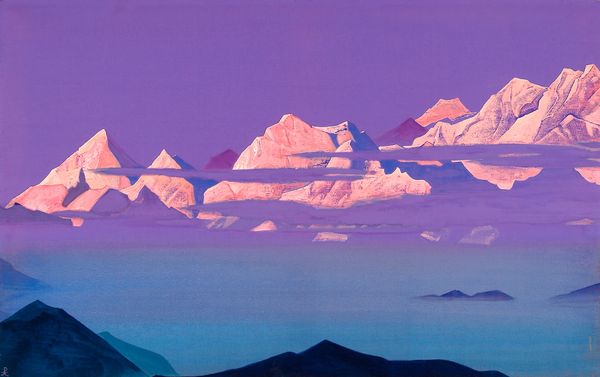

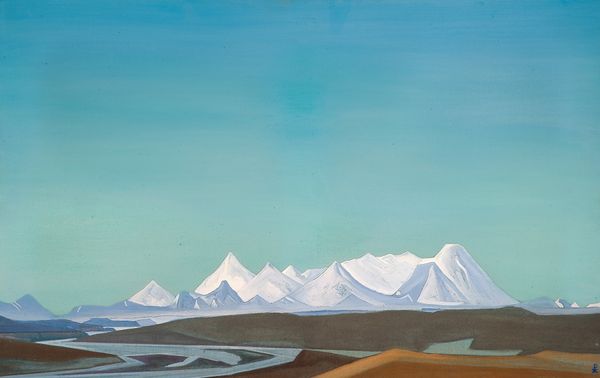

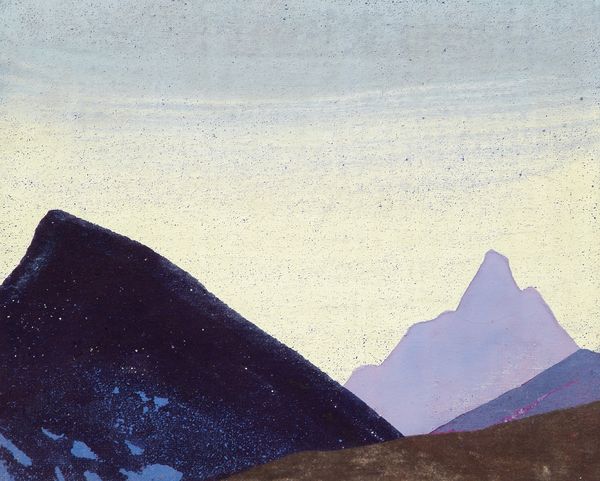

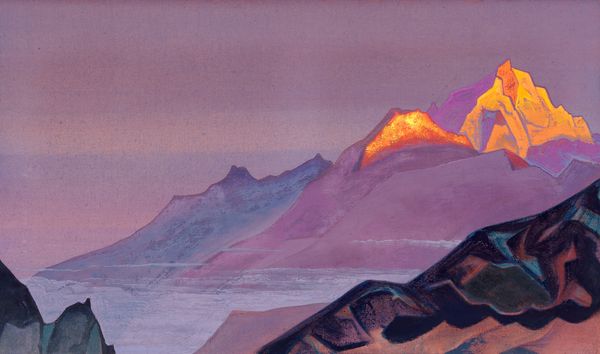

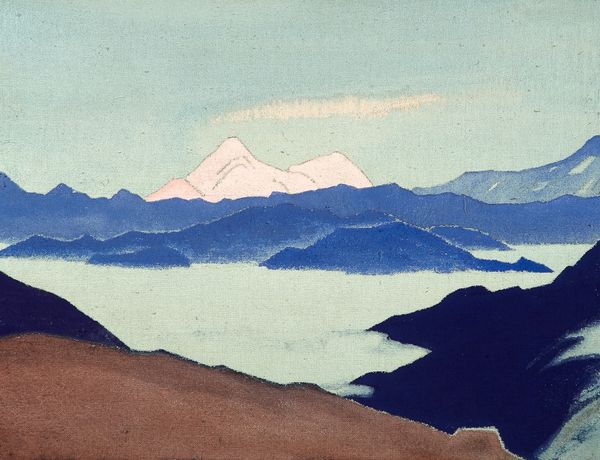

Curator: Editor: So, here we have Nicholas Roerich’s “Tibetian Lakes” from 1933, done in tempera, supposedly en plein air. It has this wonderful, almost dreamlike stillness. I’m really struck by how the paint application, though simple, creates such a powerful sense of place. What do you make of it? Curator: From a materialist perspective, Roerich’s choice of tempera is key. Tempera allows for layering, creating those subtly shifting planes of color, but it’s also a relatively fast-drying medium. That speaks to the conditions of painting outdoors in a place like Tibet—speed and efficiency would have been essential for on-site work. What does this suggest to you? Editor: Well, maybe that Roerich was less interested in capturing the exact detail, and more focused on quickly conveying the overall feeling and the grand scale of the landscape using the tools available. Curator: Exactly. And think about the socio-political context: Roerich was not just an artist, but also an explorer, deeply interested in the spiritual traditions of the region. This landscape wasn’t just a scenic view, but part of a larger project of cultural engagement and, arguably, appropriation. How do you think the use of specific pigments might connect to the location portrayed? Editor: Maybe he used locally sourced pigments when possible, tying the artwork back to the physical place even further, though that might not have always been feasible... that could be a very interesting way to ground it in its origins. Curator: Precisely! By considering these aspects, we move beyond the purely aesthetic and engage with the painting's production as a form of cultural and even colonial practice. Editor: This approach to the material really opens up a new way to understand the work. I definitely wouldn't have considered the cultural impact of the tools Roerich had at his disposal before this conversation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.