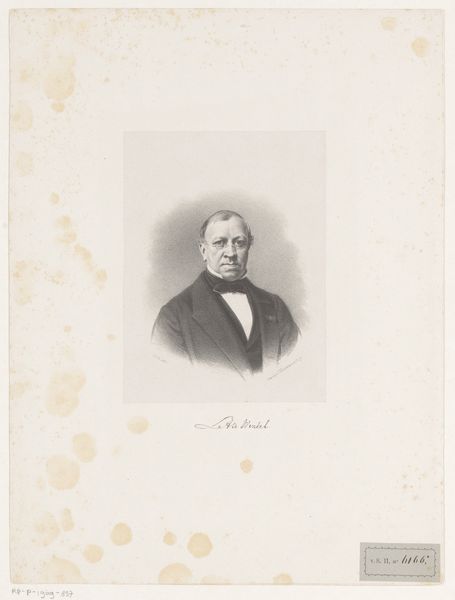

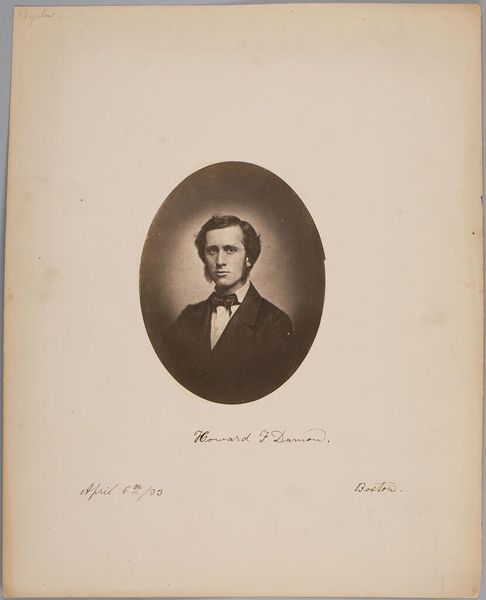

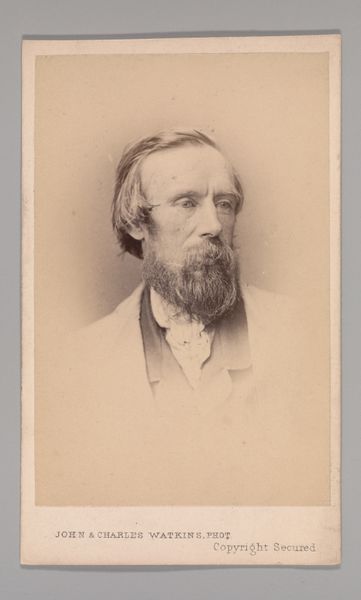

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Alphonse Amédée Baril, as the maker, provides us with the portrait, in gelatin silver print, of Mr. Sangnier, dated sometime between 1855 and 1885. Editor: Oh, a classic portrait! My first impression? Dignified. Stern, but dignified. The tones are warm, almost sepia, which gives it that timeless, serious feel. Curator: The gelatin silver process, becoming prominent around this period, involved coating a paper base with light-sensitive silver halides, fixed with chemicals. It provided sharper details and mass reproduction, influencing photojournalism and personal documentation. Editor: It's amazing how the tech shapes the art, isn't it? You get that incredible detail you were talking about; look at his beard! But there's still a softness that the artist captured—like Mr. Sangnier is staring right through the camera, maybe even into your soul. Curator: These portraits reflect the democratization of image-making and dissemination as technology advances. Analyzing mass image creation unveils a critical analysis of identity, authority, and the culture of collecting images. How accessible are portrait commissions or family mementos now compared to previous portrait traditions in oil or painted media? Editor: Right, like suddenly *everyone* can participate, not just the aristocrats getting their oil paintings done. There's a social shift built into that image, that sense of wider representation that’s captured by it, which is interesting, too, as it looks so austere and elite. You know, there is an everyman element with this gelatin silver print compared to what came before. Curator: His suit, a tailored, structured ensemble of wool—what stories could these objects and garments communicate from this timeframe and context? And also to later observers, like you and I today? Editor: Funny how a stern gaze and a good suit transcends time, really. There is a lingering resonance to these kinds of images. Curator: Precisely. It demonstrates, for me, a convergence of photographic technology and class self-representation in 19th-century bourgeois society. Editor: Well, looking at this has definitely given me a renewed appreciation for how photography democratized art. Cheers to that!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.