Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 5.1 × 10.9 cm (2 × 4 5/16 in.) page size: 27 × 34.8 cm (10 5/8 × 13 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

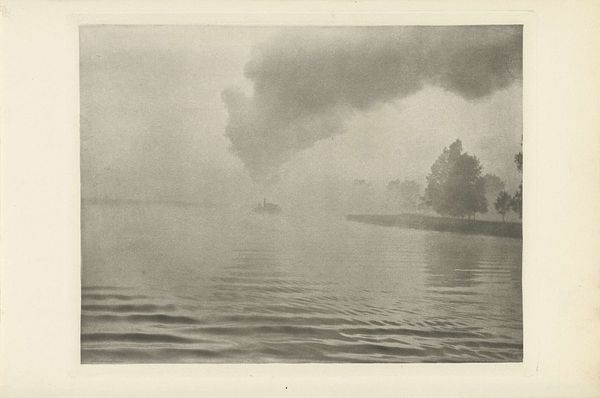

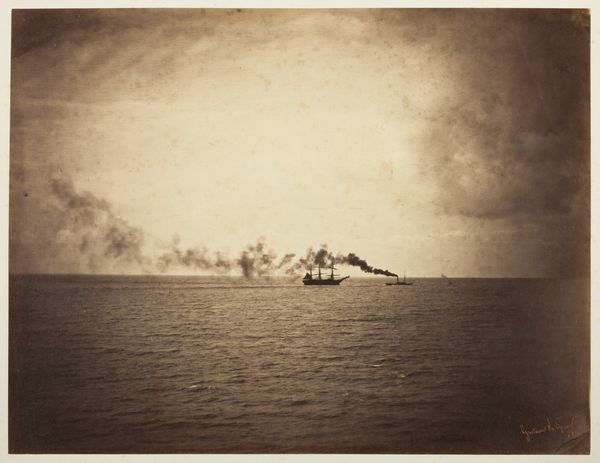

Editor: This is "Lake Lucerne," a gelatin-silver print by Alfred Stieglitz, possibly from the mid-1890s. The scene feels quite serene, despite the presence of what looks like a steamship billowing smoke in the distance. There's a real sense of stillness in the water. What draws your attention in this piece? Curator: That sense of stillness is deceptive, isn't it? What Stieglitz captures here is not just a landscape, but a moment in time where the industrial revolution, represented by that steamboat’s smoke, is actively reshaping the natural world. How do you think that tension plays out, not just visually, but considering the broader social and environmental anxieties of the late 19th century? Editor: So, it’s about more than just aesthetics; it’s a commentary on the changing landscape. The small rowboat in the foreground seems almost dwarfed by the industrial presence. Curator: Exactly. Consider the pictorialist movement Stieglitz was part of, and its complex relationship with modernity. He wasn’t simply documenting; he was actively constructing a narrative. The softness of the image, achieved through the gelatin-silver process, romanticizes the scene even as it acknowledges the encroachment of industry. Is he lamenting a loss, or perhaps hinting at a future, or even a forced co-existence? What perspective do you think Stieglitz has through the framing? Editor: I guess it's both, a bit of mourning for what's being lost, but also a recognition that this new industrial era is here to stay, that perhaps romanticizing nature and progress is a method of acceptance. Curator: And in whose name are we mourning, and whose progress are we measuring? Whose landscape is being reshaped, and who has agency in its remaking? We must never take photographs as evidence, but rather a testimony from a subjective narrator. Editor: That really changes how I see it. I initially just saw a pretty picture, but now it's a document filled with contradictions, anxieties and potential commentary about power. Curator: Precisely! It's in these nuances that we can unlock deeper understandings of not only the artwork itself, but the era that shaped its creation, and in turn how photography was already, at the time, complicit with progress narratives. Editor: This conversation made me realise that sometimes the most powerful statements are found in what seems the quietest of images. Curator: Indeed, and how the act of looking itself is never passive, but is an engagement with cultural and historical forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.