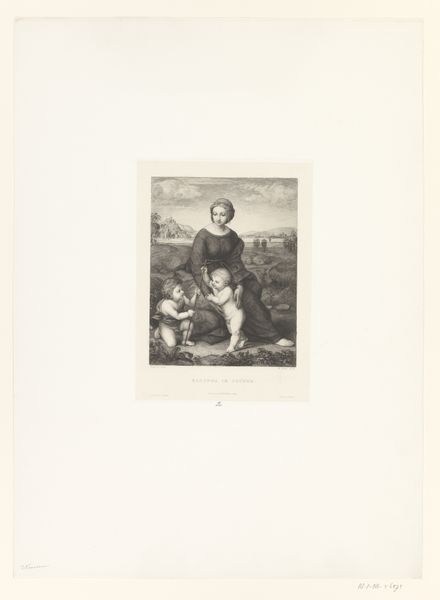

Dimensions: height 209 mm, width 157 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

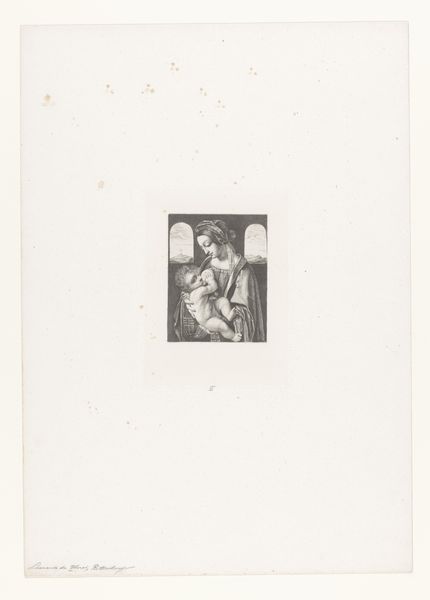

Curator: This print, dating sometime between 1857 and 1914, is titled "Vrouw met kind op schoot," depicting a woman holding a child. We attribute the work to Nikolay Semyonovich Mosolov. What are your first thoughts? Editor: My immediate reaction is tenderness. The image emanates a gentle intimacy; the figures seem to share a private world. I wonder about the power dynamics at play. Is this about idealizing motherhood, or does it speak to the socio-economic vulnerabilities inherent in those relationships? Curator: The composition does resonate with classic Madonna and Child imagery, which traditionally emphasizes a sacred bond and often masks power imbalances. The use of etching and pencil introduces a raw, almost unfinished quality to the portrait, perhaps inadvertently acknowledging the daily realities and labor inherent in motherhood, but largely glossed over by iconic representations of maternity. Editor: The details are remarkable; notice how the crown adorning the woman has very faint Christian symbols such as crosses. I wonder if those symbols allude to secular, or perhaps even pagan blessings, projected onto motherhood and familial well-being. It brings me back to pre-Christian ideals of female authority and power. Curator: I'm intrigued by the way you trace those connections. Mosolov, as an academic artist working within a romantic tradition, was deeply embedded within societal norms but he still may have drawn from classical ideals of beauty as he developed this print, even unconsciously referencing a rich tapestry of earlier visual vocabularies around mothers. I also feel like the way he captures shadow speaks to their vulnerability, which can sometimes romanticize victimhood or draw pity and donations. Editor: That interplay between tradition and the specifics of the period is fascinating. I see it as more than that; I think that she looks pained. It hints at an entire lifetime within this isolated sketch; a world of private burdens contained within domesticity. Curator: Your point reminds me that art is never neutral; even what seems like a simple domestic scene speaks volumes about the cultural values and social realities of its time. Editor: Indeed, a dialogue with the past allows us a deeper reflection on our own present. What remains, and what do we reimagine for the future?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.