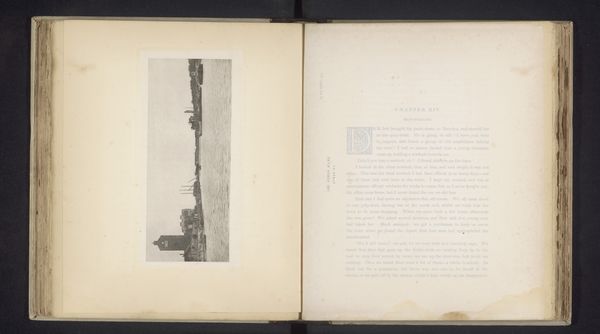

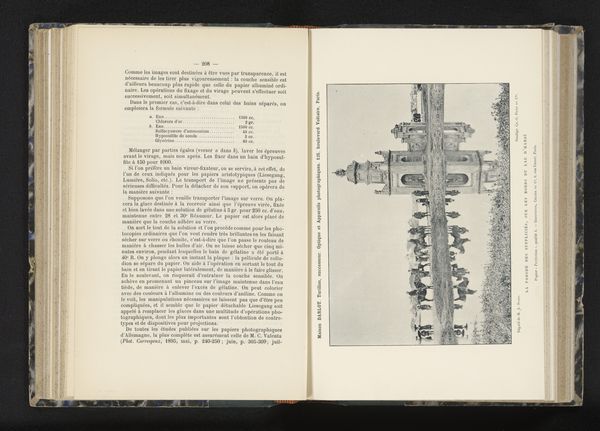

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

#

building

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have an albumen print entitled "Modern Bombay." Though its author is currently listed as anonymous, the piece dates to sometime before 1893 and forms part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: There's a somber beauty to this early photograph. The skyline stretches far, hinting at a bustling port city. Even in monochrome, the buildings project a sense of grandeur that is weighed down by the density of it all. It’s serene yet feels burdened somehow. Curator: "Orientalism" immediately springs to mind as a representational context here, an aesthetic and ideological frame firmly in place by the late nineteenth century. Images like these became crucial tools for constructing perceptions of colonized lands. How might this cityscape reflect power dynamics at play? Editor: It is a document embedded in power dynamics, that’s undeniable. I see how the photograph freezes a specific narrative, one where progress is showcased through imposing colonial architecture and infrastructure, probably financed at the expense of Indian communities. Where are the ordinary lives, the markets, the diverse neighborhoods—filtered out to craft a specific imperial fantasy. Curator: Precisely! This photograph becomes an artifact ripe for our interrogation. As an albumen print, part of photographic albums from the era, its value was multiplied and amplified as these objects moved through the colonial system. It catered to European audiences' thirst for visualizing the so-called exotic East. Editor: Exactly. We must resist accepting its perspective uncritically. The print may depict Bombay as a modern metropolis but what stories does it obscure through framing and selection. What price did those pictured in it pay for "progress"? We have to look at the photographic gaze critically and acknowledge the role of this seemingly innocuous image in shaping an empire. Curator: It prompts me to reconsider the politics of image-making itself—who controlled the lens, what were their intentions, and whose stories are privileged over others? I wonder if it moved through travel societies, scientific circles, world fair exhibits? Editor: The challenge, then, becomes deconstructing the aesthetic surface to reveal those layers. Who did the piece actually serve and to what ends, both then and now, and how do we, as an audience, subvert colonial nostalgia? I see it as a document requiring deconstruction rather than as a celebration of progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.