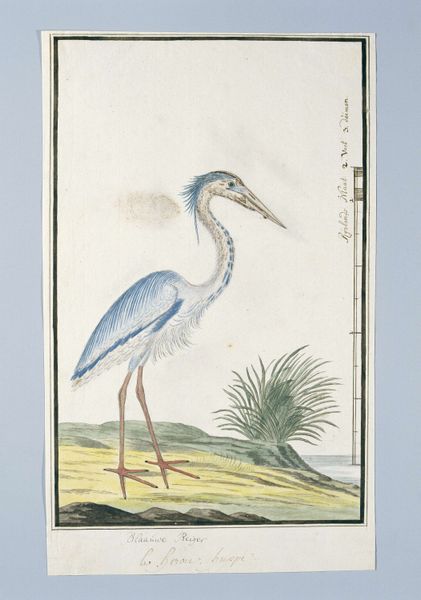

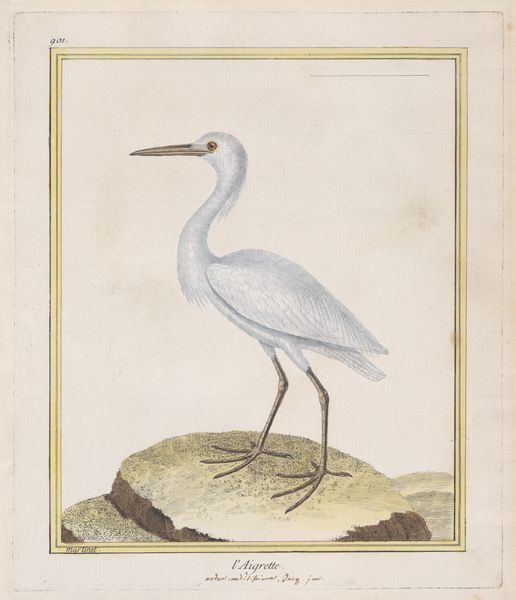

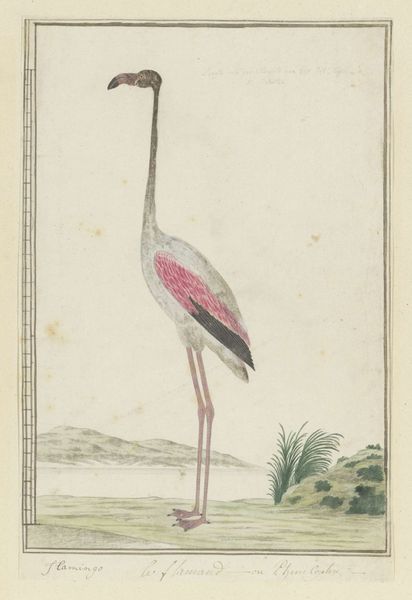

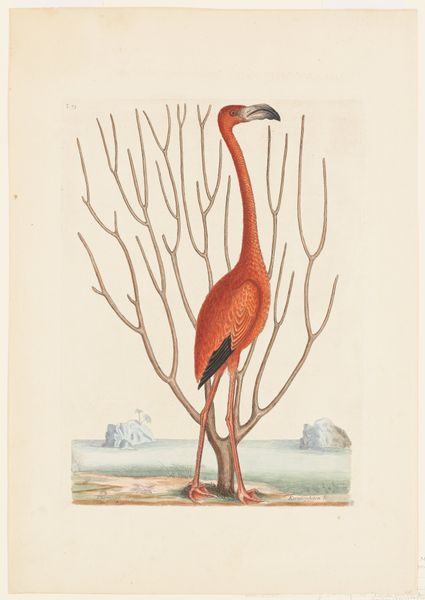

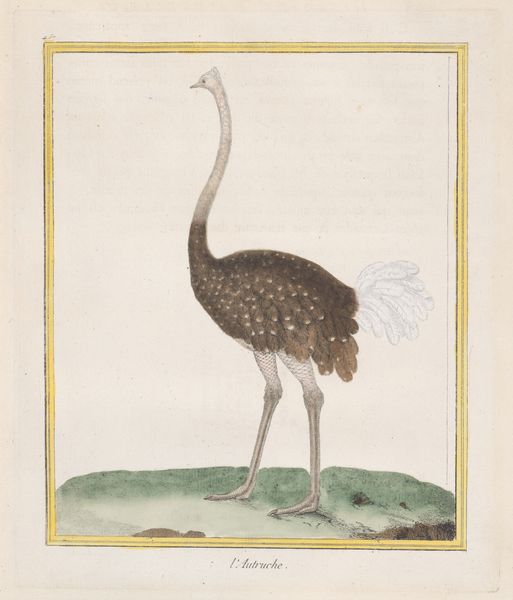

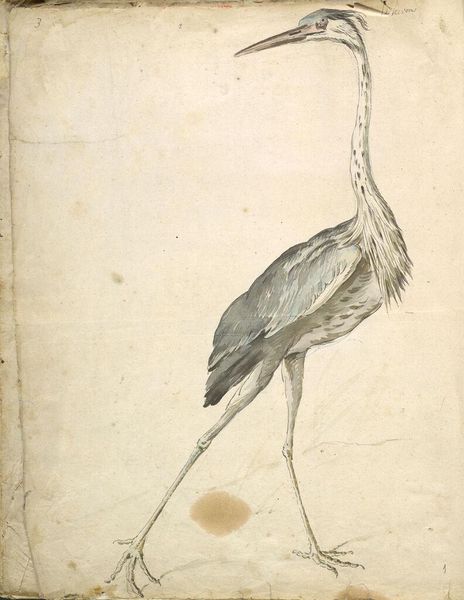

drawing, watercolor

#

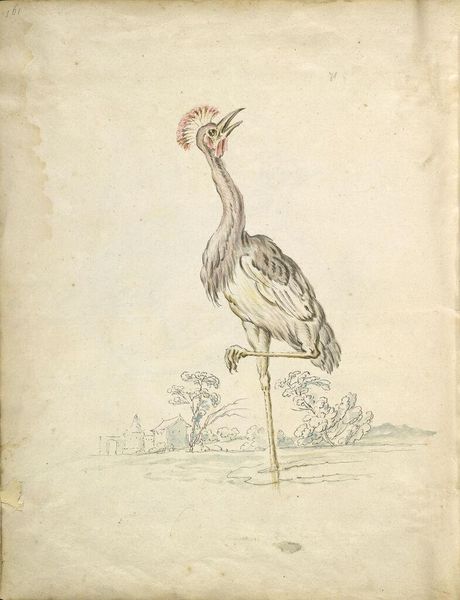

drawing

#

animal

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

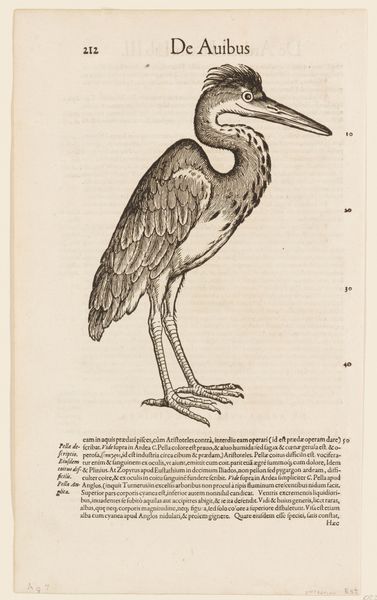

line

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 403 mm, width 252 mm, height 360 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Robert Jacob Gordon's "Threskiornis aethiopicus (African sacred ibis)," likely from 1778, a delicate watercolor and ink drawing. It’s so lifelike, but the coloring is muted. It almost feels like looking at a scientific illustration from a time when exploring nature was also about staking colonial claims. What's your interpretation? Curator: It's a brilliant observation! I see this image, and others like it from the period, as inextricably linked to the project of colonialism. Consider the act of drawing and naming a species, literally capturing and classifying it. How does that mirror the larger imperial project of claiming territory and subjugating populations? Editor: That's a really interesting point. It's not just a neutral observation, but an active participation in a system. The artist's perspective is always present, then? Curator: Absolutely. Gordon was a military man in the Dutch East India Company. This drawing, though seemingly objective, reinforces European dominance through a "scientific" gaze. The "natural" world became another territory to be mapped and controlled. Editor: So, even in what seems like a simple nature drawing, we can see the complexities of power and control at play? Curator: Precisely. What we see on the surface–a bird, a landscape–masks a deeper narrative of colonialism and its impact. It prompts us to question whose perspectives are centered and whose are marginalized. Editor: That definitely changes how I see it now. I will now always have more questions. Thanks. Curator: Indeed, asking those questions is the first step in challenging the status quo. Recognizing art as a form of social commentary can truly transform our view of history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.