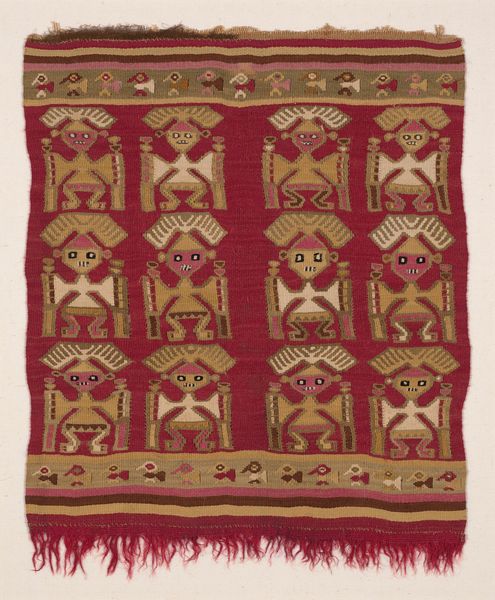

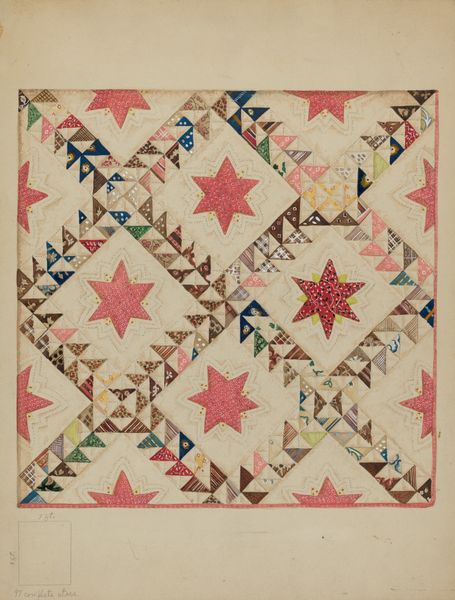

weaving, textile, cotton

#

pattern heavy

#

weaving

#

textile

#

geometric pattern

#

abstract pattern

#

organic pattern

#

geometric

#

repetition of pattern

#

vertical pattern

#

pattern repetition

#

cotton

#

layered pattern

#

funky pattern

#

combined pattern

#

indigenous-americas

Dimensions: 23 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. (60.33 x 59.69 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have the "Cofradía Tzute for Santos," made around 1940. It's a vibrant textile artwork currently held here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My first impression is joy. The piece really vibrates with energy, that red contrasting with the pale stripes, those quirky little bird and geometric motifs scattered all over. Curator: Precisely. This Tzute, a woven cloth, most likely of cotton, embodies a confluence of cultural and social factors. It was crafted within the context of the Cofradía, a religious brotherhood common in some Indigenous communities of the Americas. These cloths were often used in ceremonies and to adorn Santos, the revered saints. Editor: Right, understanding this cloth requires a dive into its specific context within that community's rituals. The Cofradías became these important hubs during periods of colonial and post-colonial upheaval where religious syncretism emerged from this dynamic—where Indigenous spiritual beliefs often intertwined with imposed Catholic traditions. So the materials, the colors, and the patterns likely held symbolic meanings tied to both. Curator: The materiality itself tells a story about the labour involved. Think about the processing of cotton, the dyeing processes employing local pigments, the skilled weaving—it represents the collective effort and artistic labour invested in this single ritual item. Editor: Exactly. And the design echoes that cultural fusion you mentioned. While we can see Indigenous weavers drawing on the backstrap loom techniques that were a historic through line of Mesoamerican societies. The specific motifs of birds could hold significance rooted in Mayan cosmology, referencing different aspects of the natural world or even social status within the community. Curator: Consider how these geometric motifs also contribute. There's a conscious design sensibility at play. It makes me think about labor, production, and how communities of makers develop patterns with complex encoded messaging over extended time. It really blurs lines between high art and craft. Editor: I think the textile challenges that neat distinction precisely. Its functionality doesn't diminish its artistic power, but actually amplifies it. And if we examine these kinds of sacred, handmade textiles through a wider decolonial lens, we see this is how a community resists erasure. Curator: It’s that beautiful entanglement of ritual practice, symbolic language, and material production. Thank you for shedding some light into the piece and unpacking it more thoroughly with me. Editor: Thanks, this was illuminating. When looking at these kind of historical pieces through our combined materialist and activist lenses, hopefully we create some space for thoughtful discussions to unfold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.