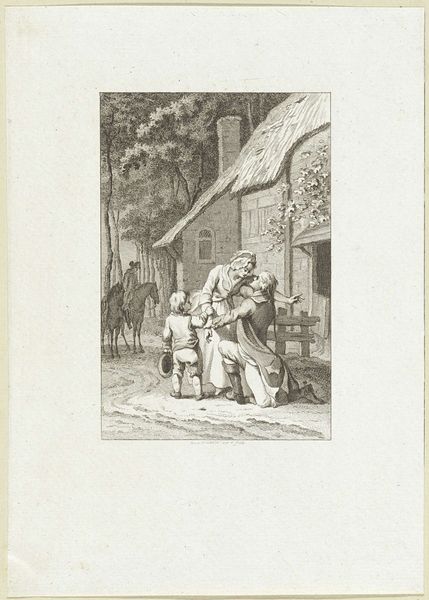

lithograph, print, etching

#

narrative-art

#

lithograph

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 211 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

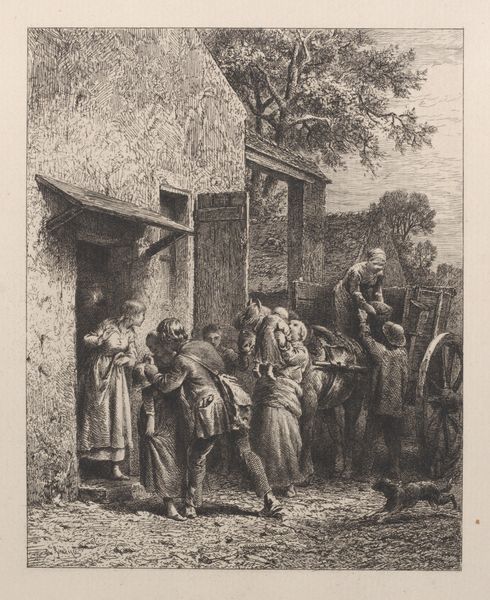

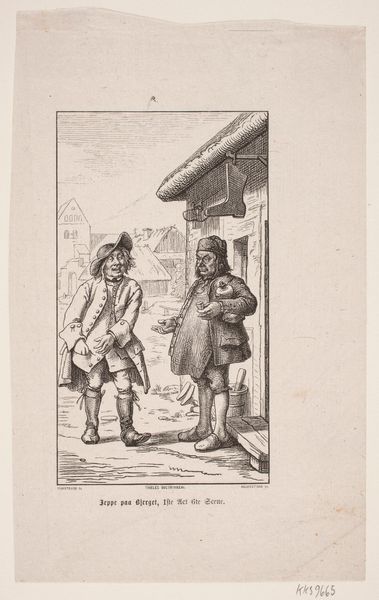

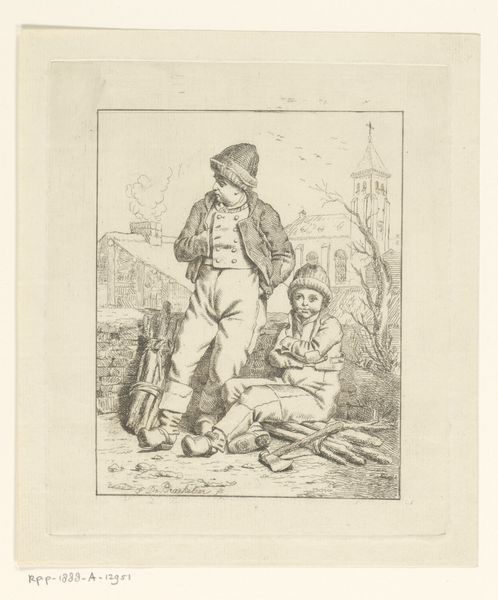

Curator: Looking at this print from 1766, "Dorpsgezicht met prentverkoper bij een man en twee kinderen," or "Village Scene with Print Seller, Man, and Two Children" by Antoine Louis Romanet, it feels incredibly ordinary. It is rendered using etching and lithograph. It is incredibly simple, yet evokes such a quiet stillness. Editor: Indeed. The emphasis seems to be less on grand spectacle and more on the daily grind and accessibility of visual culture. Curator: The artist is French. We see a print seller displaying his wares before what appears to be a small family group in front of their modest dwelling. Note the details of his garb: the jacket, hat, even his stance suggest his working-class identity. It draws my eye to the contrast between the detailed depiction of the people versus the simple shapes that compose the building. Editor: And that very "ordinary" scene is ripe with implications, isn't it? The way this itinerant seller provides these prints brings up interesting questions of artistic accessibility. Who is afforded art? Why? It isn’t necessarily intended for the elite. Curator: Precisely. This is art being brought directly to the consumer. We might ask questions about the paper used, the ease of reproduction inherent in the printmaking process and what this reveals about artistic distribution in 18th century Europe. How did people at the time experience artworks like this? Were they decorations? Social commentary? Aspirational tools? Editor: Possibly all of these! By depicting a transaction like this, Romanet highlights that relationship between production, distribution, and, finally, domestic life. Curator: Consider the materials, the very cheapness and commonality of the print. And also what is actually being traded: mass produced images and representations of nobility perhaps? Its portability facilitated its journey all the way from the artisan's workshop to this rustic home. Editor: So we begin to see these humble prints not merely as aesthetic objects but as active agents within a wider socioeconomic exchange, helping common folk connect with, and perhaps interpret, the events and images of their era. Curator: Absolutely. It challenges notions of fine art. This piece demonstrates the accessibility of artistic practices and its relevance in reflecting societal structures, bringing artistic representation into spaces beyond just galleries or museums. Editor: That’s what truly excites me—how a seemingly simple street encounter throws light on broader political and social structures—and that this dialogue begins with the humblest materials. Curator: Yes, its simple medium makes this a very profound study in the relationship between class, artistic production, and circulation within 18th century French society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.