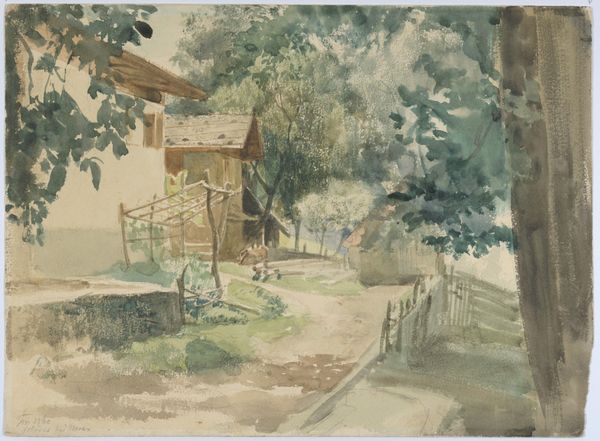

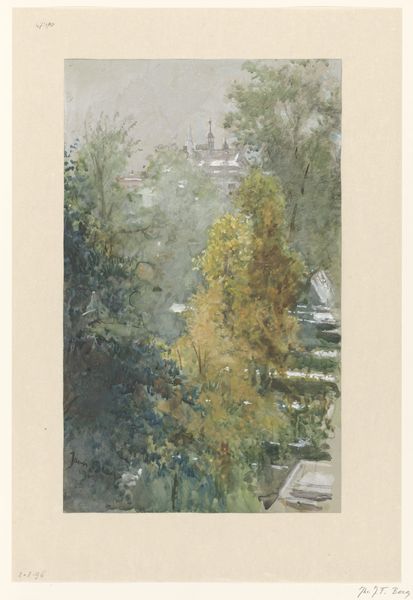

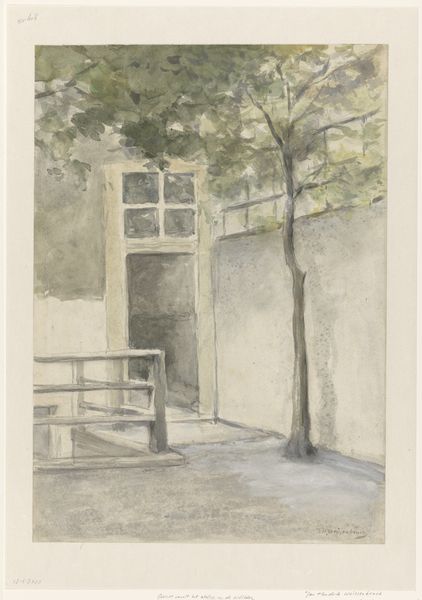

plein-air, watercolor

#

water colours

#

dutch-golden-age

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

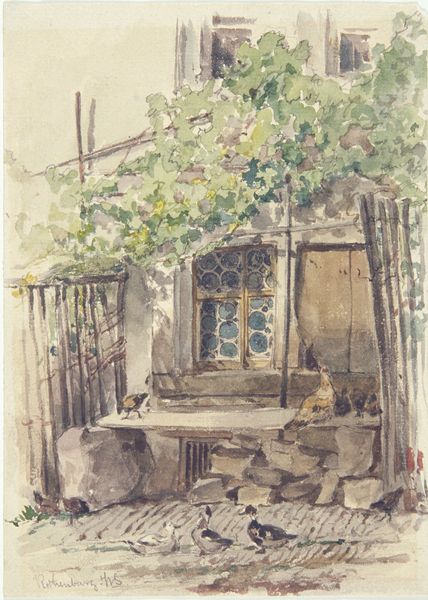

watercolor

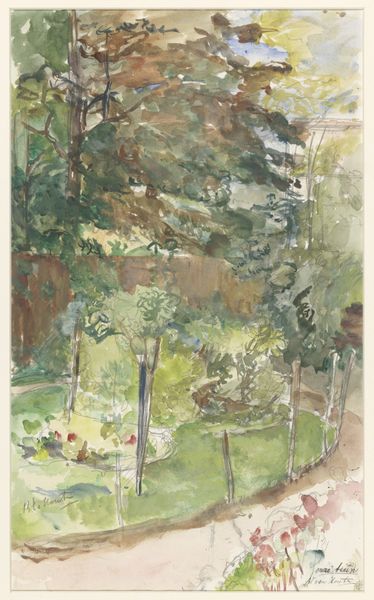

Dimensions: height 321 mm, width 219 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Johan Hendrik Weissenbruch created "Zonnig hofje," a watercolor painting rendered in his loose, impressionistic style, sometime between 1834 and 1903. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. What springs to mind for you as you observe it? Editor: Initially, it whispers of hushed mornings, a backyard awakening under a veiled sky. It is incredibly intimate in scale, and rendered with a restricted palette. I get a sense of modesty, as if documenting labour done in the domestic sphere was as simple as making a plein-air watercolour. Curator: You're picking up on something quite vital! Weissenbruch, devoted to working en plein air, felt a spiritual kinship with nature. Light and atmosphere were paramount. You almost sense him attempting to trap and transpose the impermanent into something we might experience forever. Do you imagine the place pictured might have an autobiographical resonance for him? Editor: It might, yes, though the visible brushwork reveals that labor as an intentional material reality; a place imagined. Weissenbruch clearly chose watercolor for its immediacy. The portability allowed him to capture the transient effects of light in situ and at a modest cost, and at pace. The paper itself, then, becomes not merely support, but substrate; integral to the experience itself. I wonder what the relative costs would have been to produce this compared to a canvas. Curator: That is quite perceptive. Thinking of labor, you might appreciate that Weissenbruch did come from humble roots. His devotion to landscape painting stemmed partly from a rejection of academic history painting that he believed too removed from lived experience. Editor: This certainly does challenge the historical preference toward depicting grand, theatrical subject matter by other members of the Dutch Golden Age. What are we to make of a sunlit courtyard captured by his very hand? It emphasizes the unvarnished and essential over some illusion of spectacle or heroism. Was this also intended for the domestic sphere? Curator: Precisely. It reflects a shift toward appreciating beauty in the everyday. Weissenbruch isn't after superficial charm; there's honesty in how he handles the architectural forms, especially the shadows that seem to breathe! It feels like an exploration of simple moments rather than an effort to portray any grand narrative. Editor: Indeed, and looking at the layers upon layers of paint, I find an interesting tension here. It is at once frugal in colour and material, and elaborate in application and gesture. It begs the question about whether his plein air works were spontaneous impressions of nature or protracted material interventions. Curator: Maybe it’s both—he did refer to watercolor as his "first love", which suggests the relationship was deeply felt! This makes me reconsider its supposed simplicity and his working process as more intense and intuitive than a more straightforward painterly undertaking. Editor: I agree completely. Looking more closely at the quality and type of paper and archival methods could lend interesting insights to better understanding his method in relation to the costs of the labour involved in making art. Thank you for your generous perspective today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.