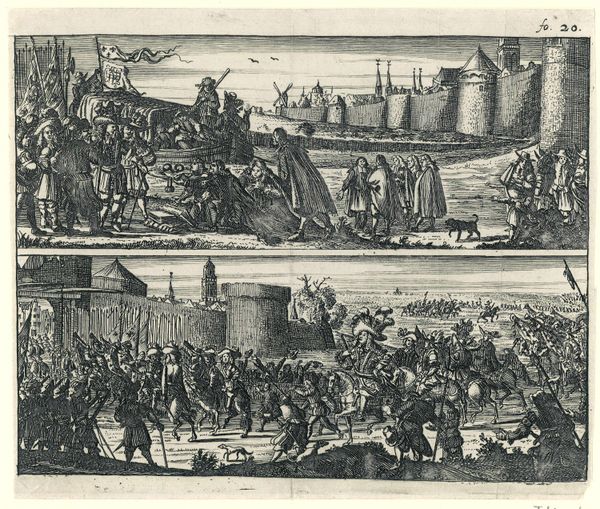

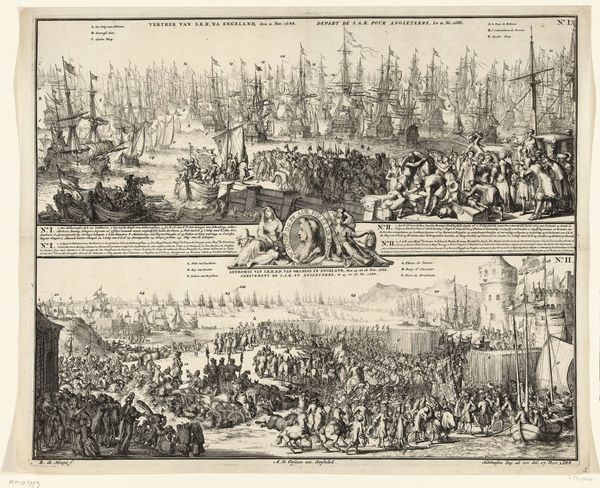

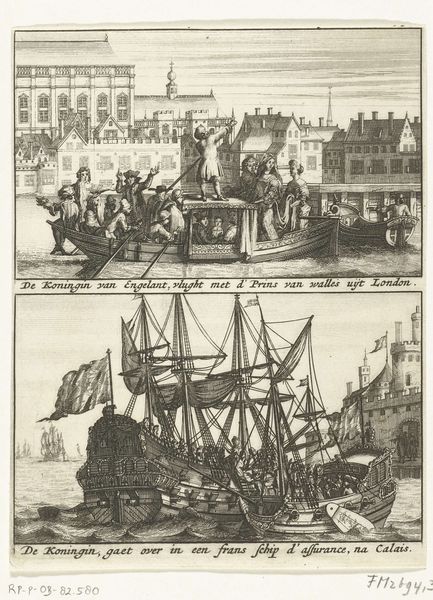

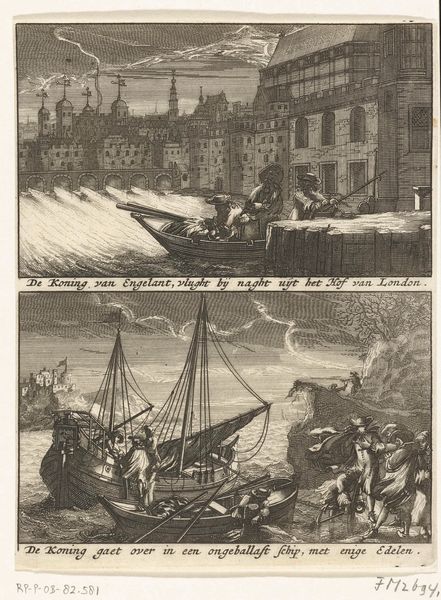

print, engraving

#

comic strip sketch

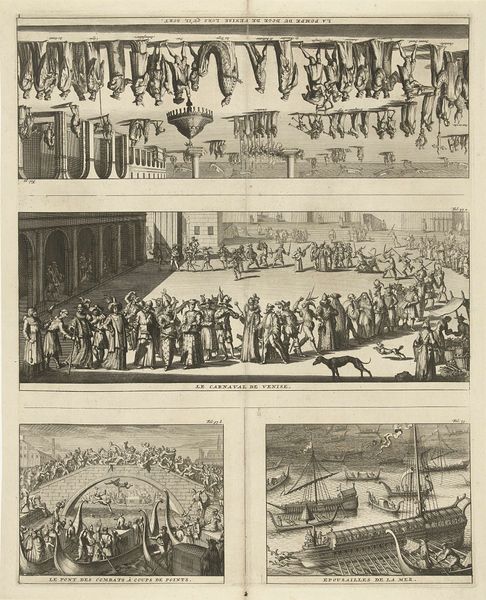

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

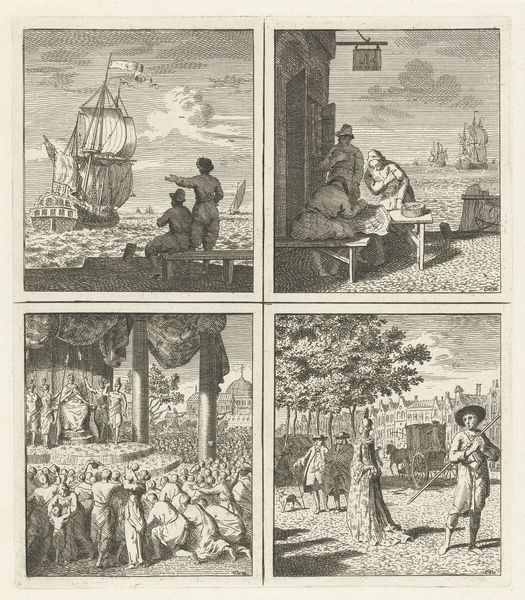

mechanical pen drawing

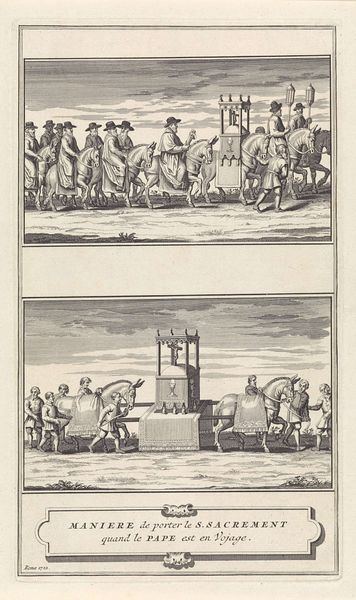

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 475 mm, width 380 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

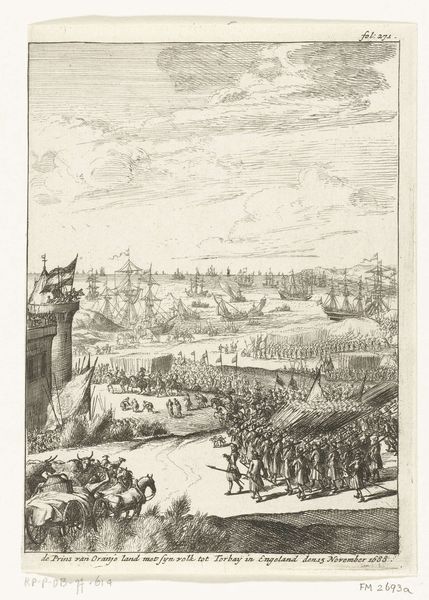

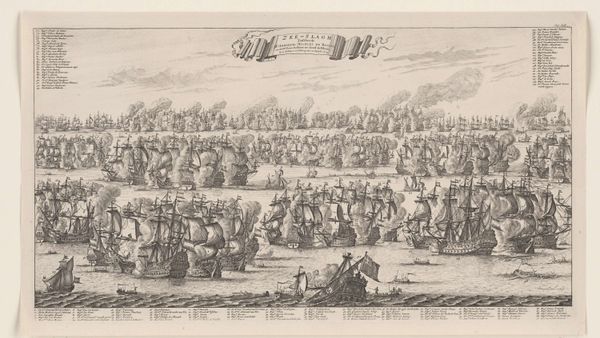

Editor: Here we have, “Zes voorstellingen van de komst van Willem III naar Engeland, 1688,” an engraving by an anonymous artist from 1688. It depicts William III’s arrival in England in six panels, almost like a comic strip. What strikes me is how staged each scene seems, almost propagandistic. What's your take? Curator: Well, you’re right to note the performative aspect. It's crucial to see this print not just as a historical record, but as a piece of political theater *in itself*. Remember, engravings like these were mass-produced and distributed widely. What purpose would this serve at that time? Editor: To, you know, get the public on board. To celebrate William's arrival, sure, but maybe also to legitimize his claim to the throne after the Glorious Revolution? Curator: Exactly! Think about the context: a bloodless coup, anxieties about succession, and deep-seated religious divisions. These images project an image of order and divinely sanctioned authority, carefully managing public perception. Note the architectural elements of cityscapes that act as a stage for his ascent of power. Consider too that there’s an intentional emphasis on processions and organised welcoming crowds, what do these elements signify in relation to power? Editor: Hmm. So, by controlling the *image* of his arrival, William's regime was solidifying its power base. Curator: Precisely! The image is as much a weapon as a document. It’s about shaping collective memory and controlling the narrative of power, especially crucial in a period of such upheaval and uncertainty. Editor: That's fascinating! I hadn't considered how deliberately these images were constructed for political ends. Curator: And understanding that active role of imagery helps us understand both the art and politics of the period. A picture can indeed be worth a thousand votes, in any era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.