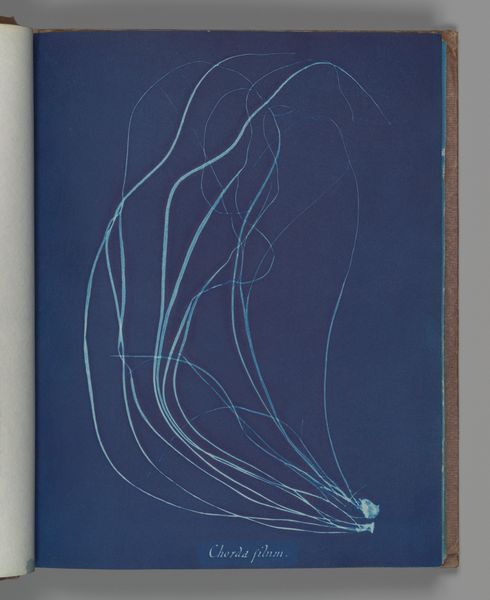

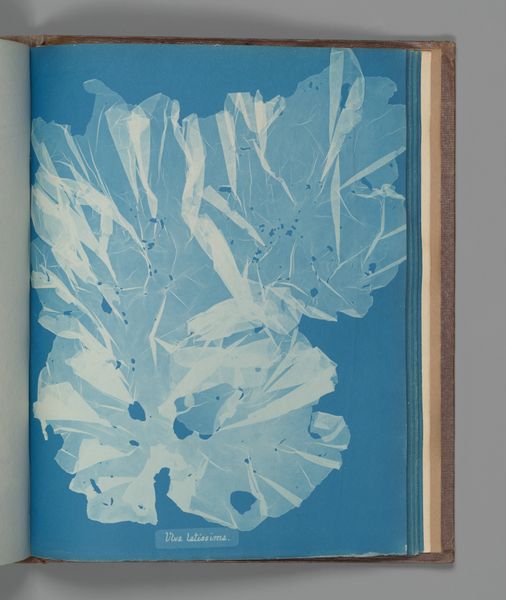

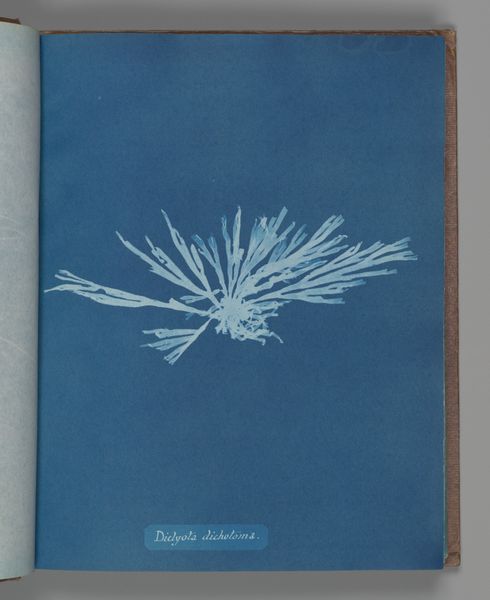

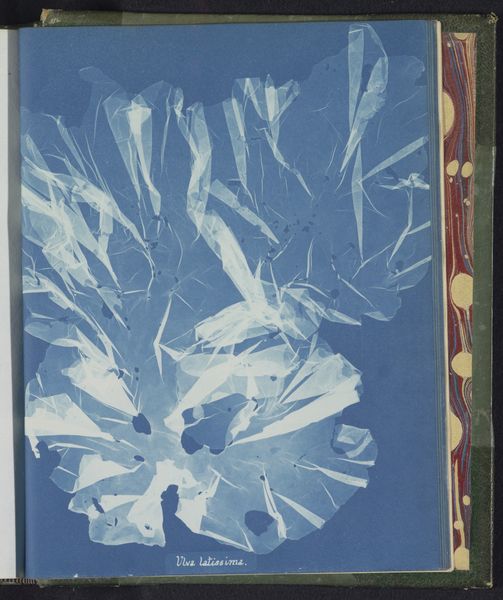

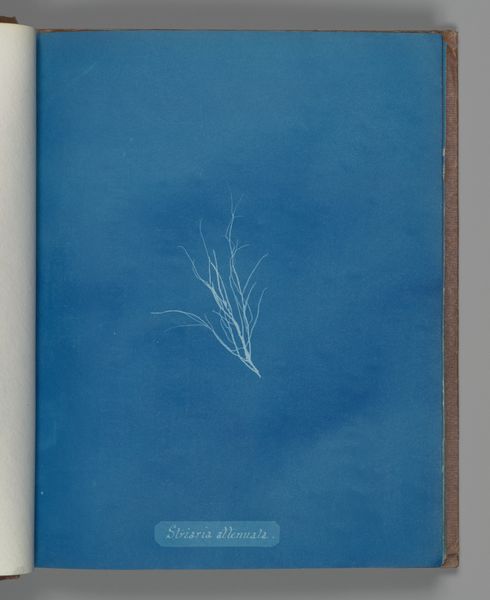

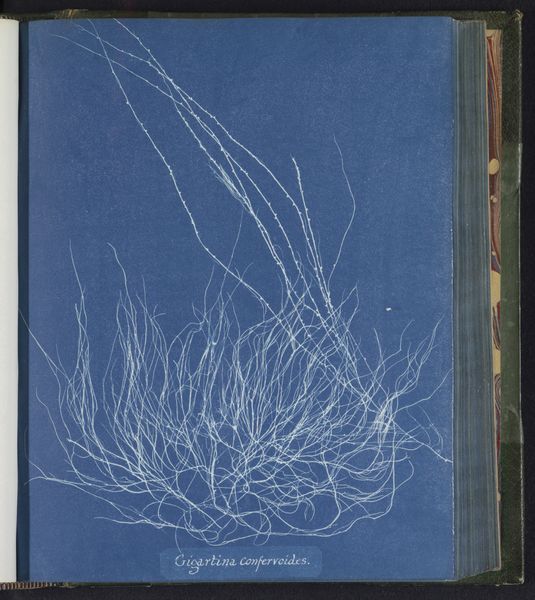

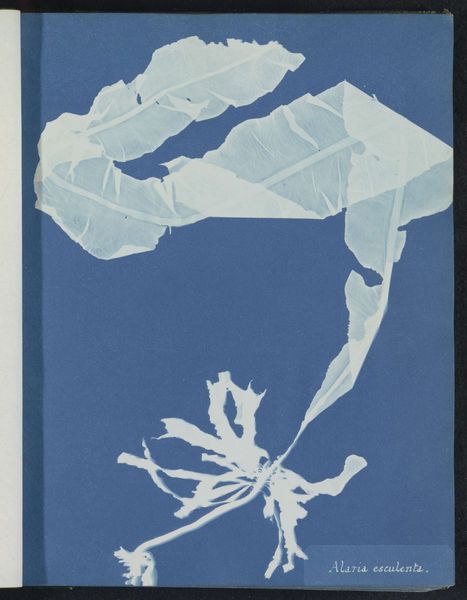

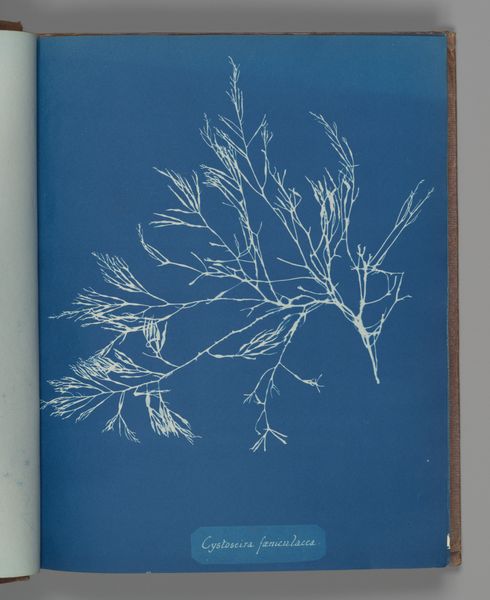

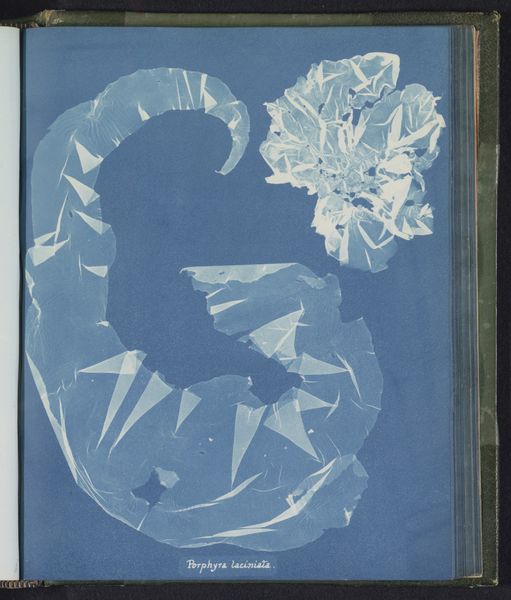

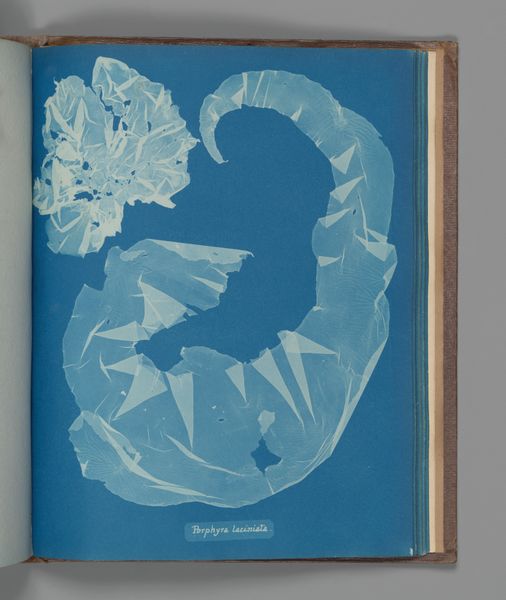

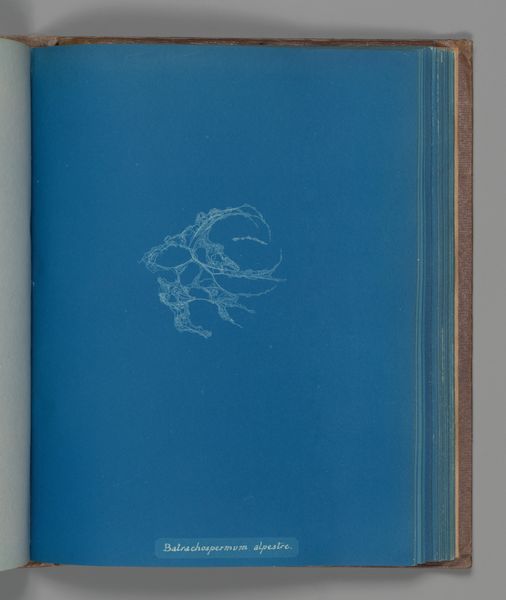

print, cyanotype, photography

# print

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

plant

Dimensions: Image: 25.3 x 20 cm (9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "Himanthalia lorea," a cyanotype made between 1851 and 1855 by Anna Atkins, residing here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s quite striking, isn’t it? Editor: Absolutely. My immediate impression is of ghostly tendrils floating against a deep, almost otherworldly blue. It's remarkably simple, but the effect is quite ethereal. Curator: And consider the process! Atkins used cyanotype, an early photographic printing process involving iron salts and sunlight. She essentially placed seaweed directly onto sensitized paper. The labor involved speaks to early scientific illustration's challenges. Editor: Yes, it blurs boundaries, doesn't it? Is this art or science? The politics of the era framed women's contributions in particular ways – Atkins being part of scientific circles yet somewhat marginalized… It forces us to consider the conditions and the networks that allowed her work to exist. Curator: Precisely. And thinking about the material—it’s not just paper, ink, and plant matter. It’s about access to specialized materials and knowledge of photographic chemistry, all circulating within particular social circles of the 19th century. Editor: It makes me reflect on museum collecting practices too. Why has this particular piece survived, when perhaps countless others haven't? And how did social perception play a role in its visibility now? Its inherent artistic qualities combined with her pioneering work are really appreciated in contemporary audiences. Curator: It speaks volumes about how we value certain kinds of knowledge and expertise. How we separate 'art' from documentation or from simple observation, perhaps? The politics of scientific visual representation at the time are fascinating to me. Editor: Agreed. The stark beauty juxtaposed with the very tangible process of creation offers much to ponder. This almost crude yet perfect, unique photogram of algae invites further study and offers new paths to explore both within and outside our usual visual frameworks. Curator: Indeed, seeing how social structures were entangled with technological advancements changes the way we see not just this picture, but so much more of what we see today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.