sculpture, wood

#

architectural modelling rendering

#

building design

#

architectural diagram

#

architectural plan

#

sculpture

#

architect

#

architectural render

#

architecture model

#

wood

#

architectural proposal

#

architectural

#

prototype of a building

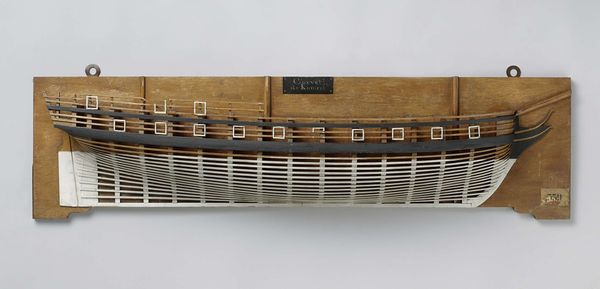

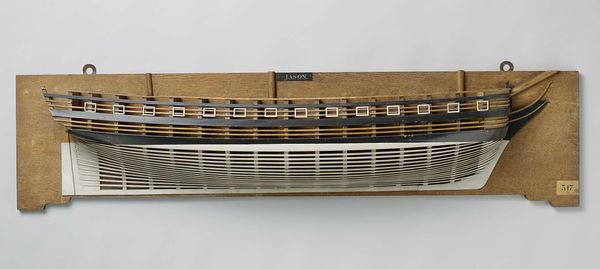

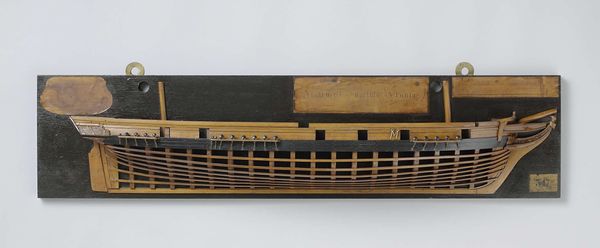

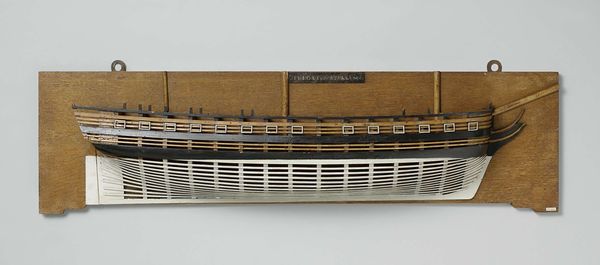

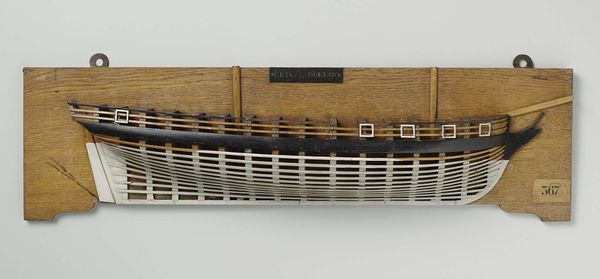

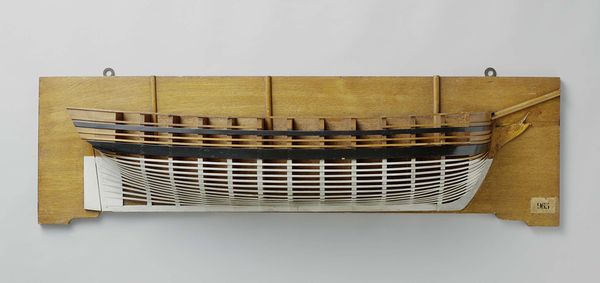

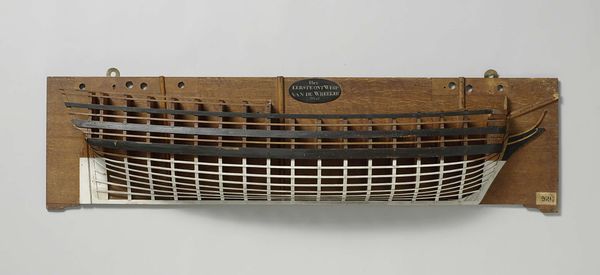

Dimensions: height 31.3 cm, width 116.7 cm, depth 14.6 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have the "Half Model of an 18-Gun Sloop of War," circa 1806. The piece is an anonymous wooden sculpture. What are your first thoughts? Editor: I'm struck by how delicate it is, almost fragile, yet it's representing something so powerful and, frankly, destructive. The exposed internal framework contrasts sharply with the solid, dark hull. Curator: Precisely. The "Half Model" offers insight into the ship-building processes of the time. Before standardized designs, shipwrights would carve these half-models to visualize and refine a ship's form before full construction. Each layer reveals the skill and artistry involved. Editor: So, it's a marriage of function and display, bridging the gap between utilitarian craft and formal representation. Consider how such models would have been viewed: both as blueprints and as symbols of naval power. Curator: Yes, this form of modeling served as a means to communicate ideas. Moreover, it helped to legitimize shipbuilding as an enterprise contributing to broader social and economic objectives during periods of conflict, a sentiment clearly conveyed in the precise detailing, like that band of window openings. Editor: It speaks to the visual language of power – and what I think is interesting is that this ‘language’ extended into various sectors. Not just navy, but its ability to enhance British trade routes globally; the legacy of which resonates even now. The construction also echoes colonial ambitions, I find. Curator: That's astute. And, given its date, the "Half Model" reflects Britain's naval dominance during the Napoleonic Wars. The sleek lines promised speed and maneuverability, features critical for asserting maritime control and projecting force across vast oceans. Editor: This really complicates the perception and creation of beauty when tied to exploitation. Still, the detail—the maker's hand evident—gives it an undeniable intimacy that I feel despite that discomfort. Curator: Absolutely. A reminder that even instruments of conflict are conceived and realized through meticulous labor, craftsmanship, and societal purpose. Editor: A compelling example of the many facets we assign objects with history. Thank you for these rich contextual points to appreciate them. Curator: Likewise. This certainly opens our eyes beyond simple appearances.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.