![Kind auf die Veranda (Sohn Titus) [Child on the Veranda, Son Titus] by Conrad Felixmüller](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2ExNTM5YzIwLWUzZmUtNDNlZS1iNDc3LTE0MmM1YTEyNjMyMi9hMTUzOWMyMC1lM2ZlLTQzZWUtYjQ3Ny0xNDJjNWExMjYzMjJfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=1920&q=75)

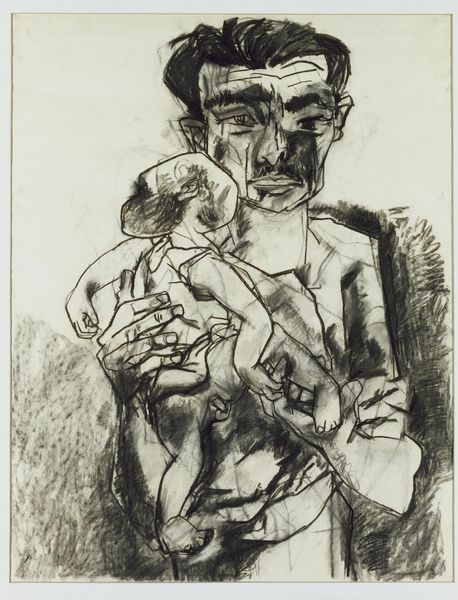

Kind auf die Veranda (Sohn Titus) [Child on the Veranda, Son Titus] 1921

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, intaglio

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

expressionism

#

cityscape

#

portrait drawing

Dimensions: plate: 12.8 × 19.69 cm (5 1/16 × 7 3/4 in.) sheet: 40.48 × 32.7 cm (15 15/16 × 12 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

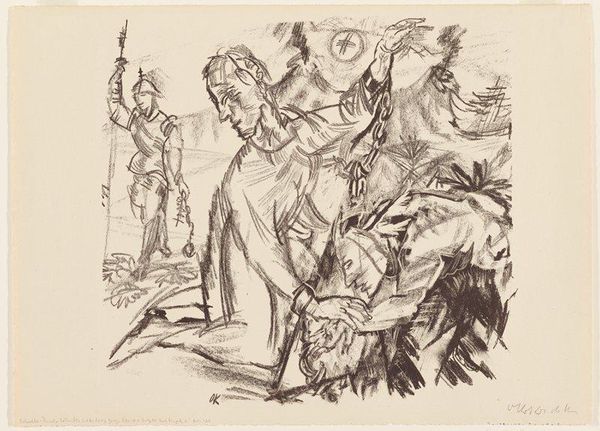

Curator: "Child on the Veranda, Son Titus," created in 1921 by Conrad Felixmüller. It’s an intaglio print, which falls under the realm of drawing due to the nature of its mark-making. Editor: It’s... unsettling. The lines are so harsh, creating an almost grotesque caricature of the child. The distorted perspective makes the outdoor space seem warped, threatening. Curator: Yes, that raw emotionality is quite characteristic of German Expressionism, the movement to which Felixmüller belonged. Expressionist artists frequently grappled with the psychological effects of urbanization and industrialization. Given that this was made in 1921, Germany was in dire economic straits. Editor: So, you're saying the artist aimed to illustrate this reality using specific expressive distortions, a certain type of abstraction... The emphasis seems to be on creating visual forms for intangible emotions rather than mimicking literal appearances. The lines themselves communicate a tension, perhaps alluding to what it would have meant to be a father, a member of the proletariat, trying to raise a child amid material suffering and political instability in the early Weimar Republic. Curator: Precisely. Felixmüller's active participation in groups that leaned into socialist political ideologies would confirm that analysis. But beyond that, there’s a fascinating intimacy here. We’re drawn into the domestic sphere, witnessing the son seemingly confined in the veranda, behind that thick wooden structure he uses as support to reach what lays beyond it. There's a tension in wanting to grow beyond that childhood context. Editor: Looking closer at the formal components: The stark contrast between the etched lines and the blank paper intensifies that sense of anxiety, right? It's as though Felixmüller is carving out not only the child's form but also his emotional state, the urban unease pressing upon him from that background of the cityscape with looming silhouettes and hurried figures in the street. It lacks comfort in terms of shape. Curator: I agree. And consider intaglio itself, the physical act of cutting into the metal plate, as a metaphor for the way that external circumstances can cut into one's life, into one's hopes for the future. It's as if the city’s struggles became inextricably linked with the destiny of this child and so many like him. Editor: That interplay of material conditions and symbolic representation is really insightful. It shows how visual choices speak beyond themselves to wider historical and political factors. It’s difficult to walk away from that etching and not think about resilience amid despair. Curator: Indeed. Felixmüller leaves us contemplating the impact of historical forces on personal narratives. The perspective shifts for the viewer too. Now, we are the parents of Titus and of other generations exposed to these realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.