#

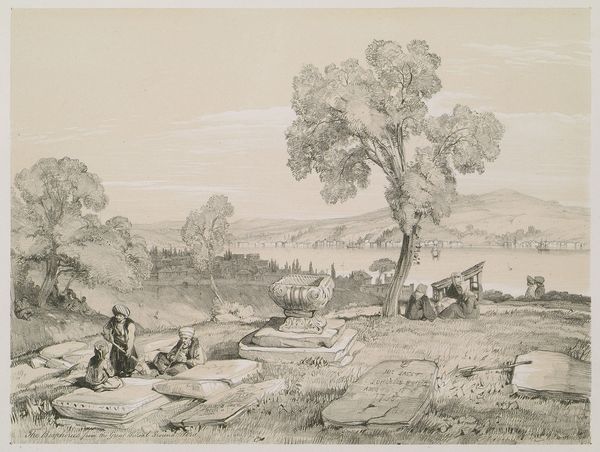

landscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

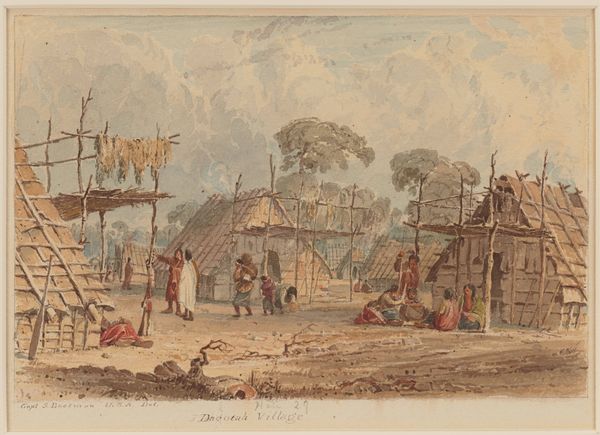

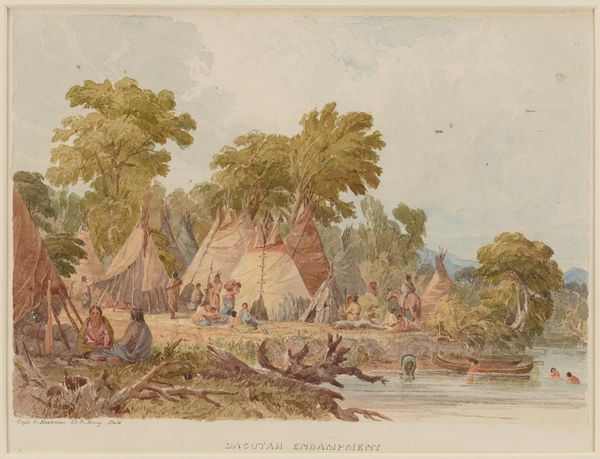

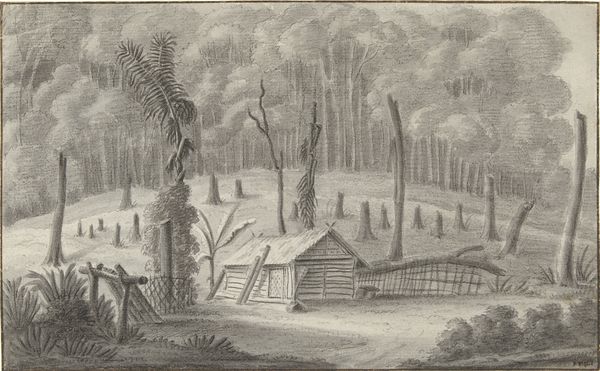

indigenous-americas

Dimensions: 6 × 8 3/4 in. (15.2 × 22.2 cm) (image)9 11/16 × 12 7/8 in. (24.6 × 32.7 cm) (sheet)17 9/16 × 21 1/2 × 1 1/8 in. (44.6 × 54.6 × 2.9 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We’re looking at Seth Eastman's "Indian Sugar Camp," created sometime between 1849 and 1855. It's a watercolor that shows, well, a sugar camp! It's so detailed and gives you this sense of a specific moment in time, like we're observing a scene unfold. I'm curious, what do you see when you look at this piece? Curator: Eastman’s work presents us with a complicated historical picture. Here, we have a genre scene, seemingly documenting the everyday life of Indigenous peoples making maple sugar. However, it’s crucial to remember Eastman was a military man, an officer. How do you think that positioning affected the creation – and the reception – of this artwork? Editor: That's a good question! Did his position mean it wasn't a neutral representation? Maybe it was biased towards how the U.S. government wanted Native Americans to be seen? Curator: Precisely. This image enters a larger discourse surrounding westward expansion and government policies toward Indigenous populations. Eastman’s position afforded him access, but it also framed his view. Consider the romanticized aesthetic – does it emphasize cultural difference, perhaps subtly justifying displacement? Is he attempting to create sympathy, or exoticizing a culture? Editor: So, it's less about pure representation and more about the social and political context shaping what he chose to show and how he presented it? Curator: Exactly. It urges us to consider who is telling the story, why they're telling it, and what power dynamics are at play in the act of representation itself. The “truth” of this image is found in unpacking those complex layers. Editor: Wow, I didn't think about how much context is packed into this idyllic-seeming landscape. It makes me think differently about art from this period. Curator: It’s a vital reminder that art doesn't exist in a vacuum. It’s always a product of its time, embedded in a web of social and political forces. Examining these forces helps us understand its true complexities.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Seth Eastman may have observed this scene on Nicollet Island, in present-day Minneapolis, which was covered in maple trees and home to several sugar camps. He depicts the hard work required to transform maple sap into sugar: chopping, pouring, hauling, stirring. There was also tasting -- including by a naked baby! A detail at left shows sap dripping into a container, the first step before it heads to the kettles for boiling into syrup. This is evidently the first time this activity was recorded by a non-Native person. This watercolor, one of 35 works on paper by Eastman in Mia’s collection, was the basis for an illustration in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s massive "Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States" (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1851-57).

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.