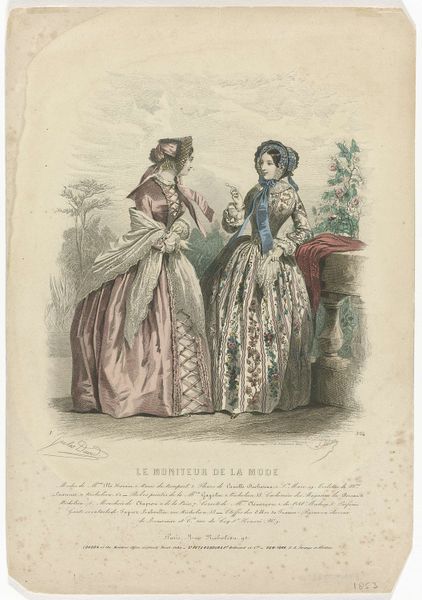

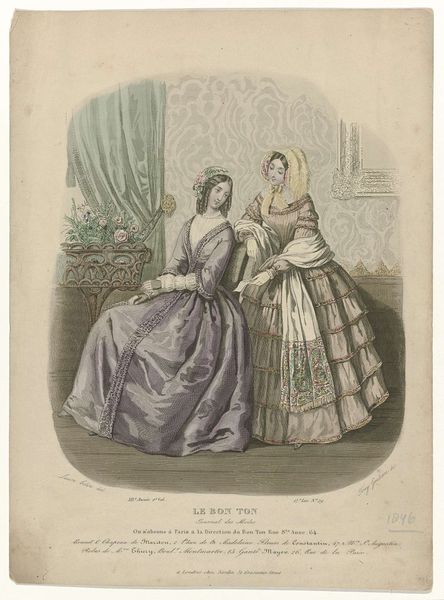

Le Bon Ton, Journal des Modes, 1861, No. 357 : Parfumerie de la Société (...) 1861

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This lithograph and watercolor print is "Le Bon Ton, Journal des Modes, 1861, No. 357," crafted by Jean Charles Pardinel in 1861. It’s more than just a pretty picture, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Initially, I'm struck by the cool color palette. The soft blues and grays lend a certain calm, almost melancholy air to the figures and the setting. The shapes, particularly the large skirts, dominate the visual field, don't they? Curator: Absolutely, and that tranquility is carefully constructed. The print comes from a journal aimed at upper-class Parisian women, dictating trends not merely in clothing but in behavior and aspirations. The subjects exemplify the ideals of femininity during the Second Empire. Motherhood as performance, a woman's position reliant on male approval, etcetera... It presents a fabricated ideal. Editor: While your points about societal constraints are valid, observe the meticulous detail in rendering the textures—the subtle sheen of the fabric, the delicate lace. It transcends simple documentation, rising into the realm of art through the skill of its execution. And the subtle washes in watercolor that tint the dresses with blues and silvers--masterful. Curator: Those very details enforce a culture of rigid expectations and reinforce hierarchies of power. To see merely beauty overlooks that the 'romantic' genre and 'decorative arts' often sanitize and beautify strict social conditions for many women. The illustration naturalizes gendered norms and roles. Editor: Perhaps, but I cannot disregard the visual language—the formal interplay of line and color, the delicate balance achieved between detail and simplicity, even in their fashionable constraints. Semiotics is important, after all. The language of adornment, dressmaking, presentation... Curator: I agree that these components warrant inspection but always in service to deconstructing hegemonic narratives. Ignoring that larger social-historical setting makes us complicit in reinforcing it. Editor: And contextual knowledge enriches but should never obscure the work’s inherent aesthetic value. One does not need a social manifesto to witness a work of art as it is displayed before you. Curator: A crucial tension, wouldn’t you agree, when examining artwork such as this—seeing it as beautiful as well as an artifact that bears social meanings? Editor: Indeed. We've perhaps unveiled the intricate dance between aesthetics and ideology embodied within Pardinel's work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.