Copyright: Public Domain

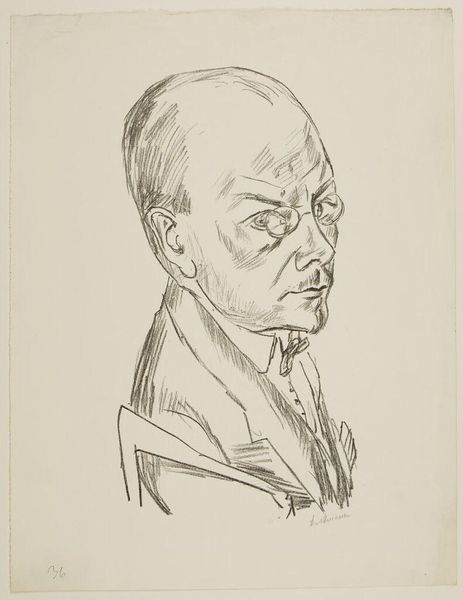

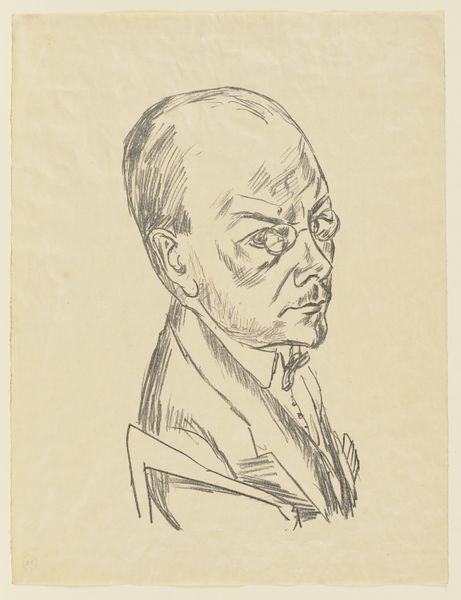

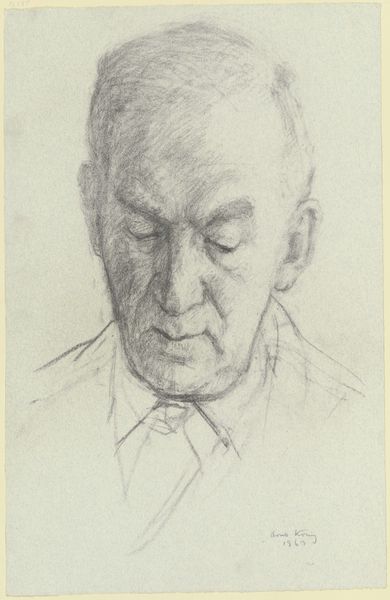

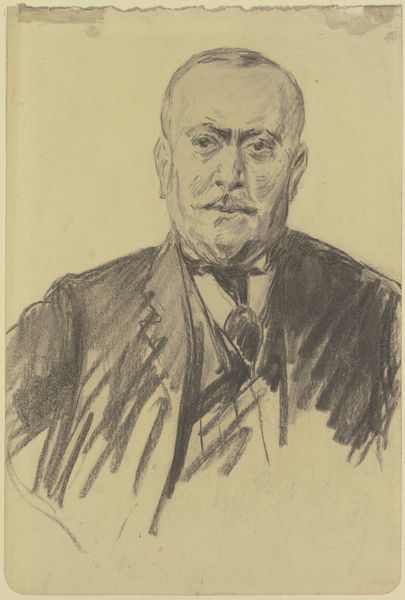

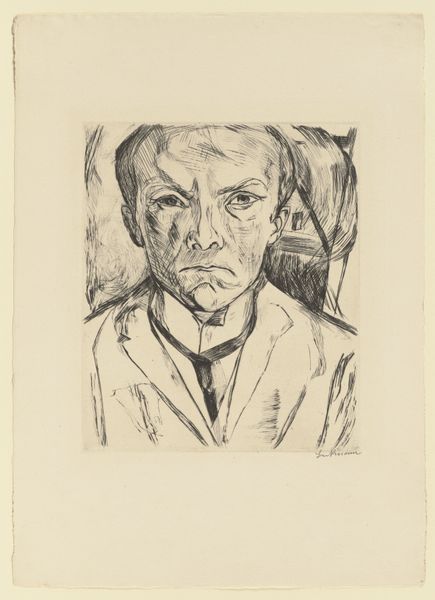

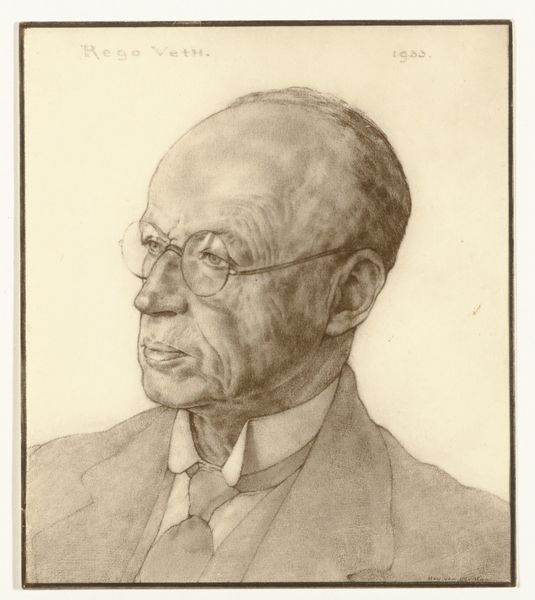

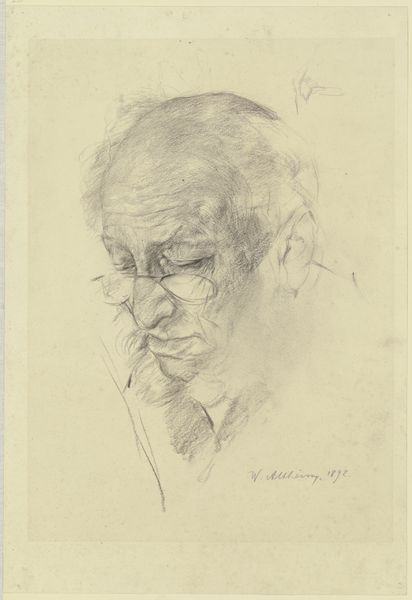

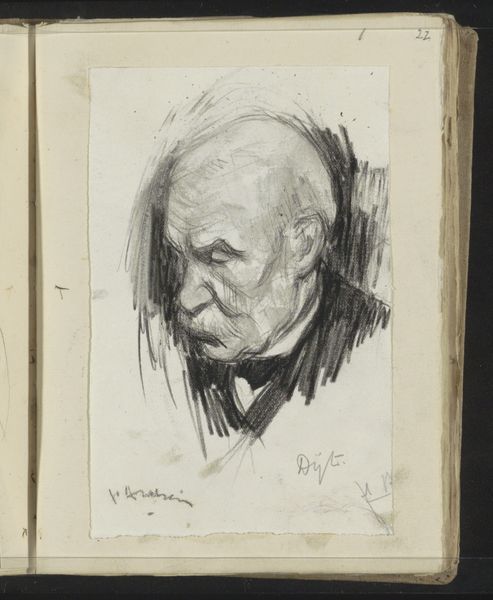

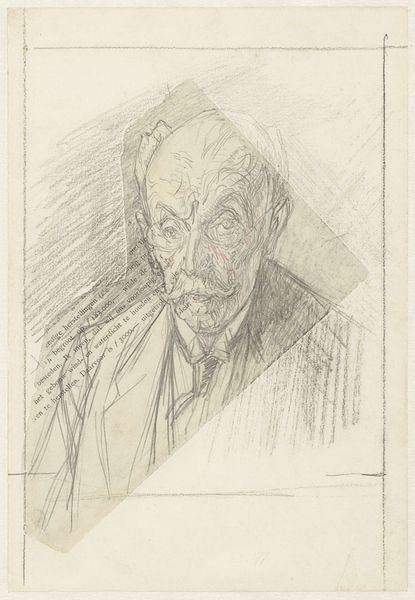

Curator: Max Beckmann rendered this pencil drawing, "Bildnis Georg Swarzenski," in 1950. It's currently housed here at the Städel Museum. Editor: It has the appearance of something quite rapid, an efficient study in tones using just pencil on blue toned paper, as if executed in a moment stolen from more demanding work. The face has such immediacy. Curator: Georg Swarzenski, whom Beckmann depicted here, held the position of director at the Städel Museum during an extremely pivotal period, specifically during the Nazi era and directly following it. We might consider how this sketch negotiates issues of cultural authority and even the recuperation of German identity. Editor: Interesting you should mention that, I immediately consider the materiality; the specific choice of materials is revealing: simple graphite on toned paper. This evokes a sense of modesty in materials that would have certainly have been chosen as part of a careful budget at that time. The work appears as a type of record-keeping, almost journalistic, as he navigates a new relationship of cultural governance within his artistic process. Curator: Absolutely. One could argue Beckmann’s choice in medium directly opposes grander, more pompous styles favored by the Third Reich, quietly defying ideological impositions through aesthetic choices. The stark simplicity lends to it a subversive edge within that socio-political climate. Editor: I notice the paper's light-blue tone as functioning to unite all, literally working with what’s to hand while maintaining careful observations throughout the making, and considering the production—or how this work circulates amongst different socioeconomic classes. Curator: In looking at Georg Swarzenski’s slightly downcast eyes, perhaps mirroring the state of the post-war cultural landscape, we witness how deeply implicated individual identity becomes in the project of national rebuilding and remembering. It serves as a very human-scaled reckoning. Editor: Right, but to add to this I feel that Beckmann’s gestural and yet economic pencil work shows an efficiency for making, and the way that the work shows his hand reveals that there’s labour and work embedded and on display. Curator: This all prompts us to reassess traditional hierarchies that separate the conceptual and the manual. Editor: The artist’s own identity and intention of this work still manages to become embedded. Overall, Beckmann gives us not just a depiction but an entry point into a deeper discourse.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

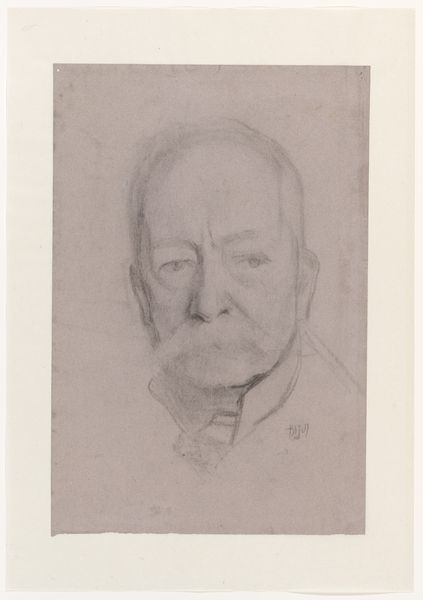

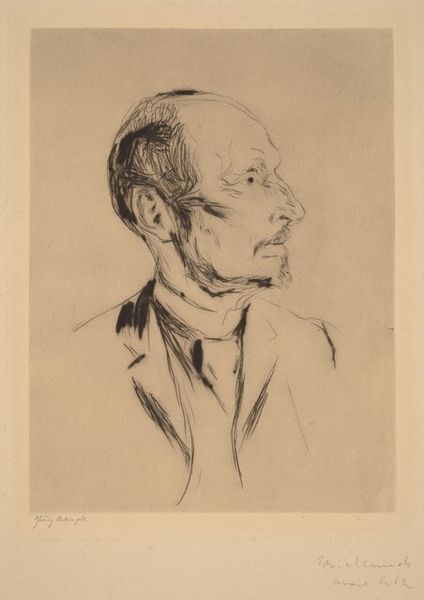

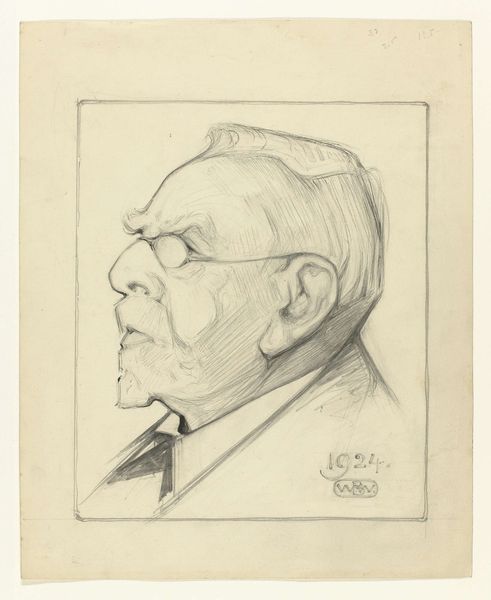

This portrait of his old friend Georg Swarzenski (1876‒1957), drawn by Beckmann on December 15, 1950, a few days before his sudden death, shows closeness and respect.[1] Swarzenski, who hasd been a Fellow for Research in Sculpture and Art of the Middle Ages at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston since 1939, came to 69th Street in Beckmann’s New York studio. He later told his son Hanns Swarzenski about the intense atmosphere and the enormous tension that emanated from the artist.[2]Looking at the viewer directly, the elderly’s earnest gaze attracts all the attention while the depicted seems to withdraw behind strong spectacles at the same time. In comparison to the lithograph produced almost thirty years prior, an impatiently searching gaze has given way to an expression of knowledge and composure. The quality of the drawing reflects the silent agreement between artist and visitor: a wordless, but emotionally charged exchange of common memories and experiences.The portrait is intended as a surprise for the 75th birthday of the art historian.[3] The idea probably came from Oswald Goetz (1899‒1960), Georg Swarzenski’s assistant from Frankfurt, who now works as a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago. In Frankfurt am Main, Swarzenski was appointed director of the Städel Art Institute in 1906. Under his direction, the Städtische Galerie was founded in 1907 and the Liebieghaus sculpture collection in 1909. Until the First World War he first acquired important Impressionists, including Vincent van Gogh’s famous “Portrait of Dr Gachet” in 1912. From Beckmann, who came to Frankfurt in 1915, he first bought the “The Deposition of the Cross”. Together they experienced the artist’s success in the 1920s, but also the growing defamation by the National Socialists coming into power. In 1933 Beckmann was removed from his teaching post at the Kunstgewerbeschule, now the Städelschule, and Georg Swarzenski, General Director of the Frankfurt Museums since 1928, was also removed from all municipal offices. Until the end of 1937, he remained director of the private institution, the Städel Art Institute, and emigrated to the United States as late as 1938.[4]“At first you’re amazed,” the tourist Swarzenski had reported after a trip to America in 1926, “when you suddenly meet a colleague or artist from Europe who follows the same paths, yet soon you take it for granted. You are introduced to people of the same attitude and convictions, who live and work there, and you finally discover that the spiritual forces are the same everywhere.”[5] Swarzenski and Beckmann were only to meet again in America, in the potentiated spiritual climate that was shaped by many European exiles and emigrants now living in the USA.[1] Letter by Georg Swarzenski to Lilly von Schnitzler dated 18.2.1951, Max Beckmann Archive, in: Lenz 2010, pp. 174‒176.[2] Bielefeld 1977, cat. 220; cf. a. the recalled model meeting of W. R. Valentiner, “Max Beckmann”, in: Erffa/Göpel 1962, pp. 83‒90, here p. 89.[3] Reproduced as frontispiece in the Festschrift Beiträge für Georg Swarzenski zum 11. Januar 1951. Essays in Honor of Georg Swarzenski, Berlin and Chicago 1951.[4] On Max Beckmann’s time in Frankfurt, see Frankfurt 1983.[5] Swarzenski 1927, p. 16. One copy of the publication published as a reprint was in Beckmann’s library.[6] Los Angeles 1997.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.