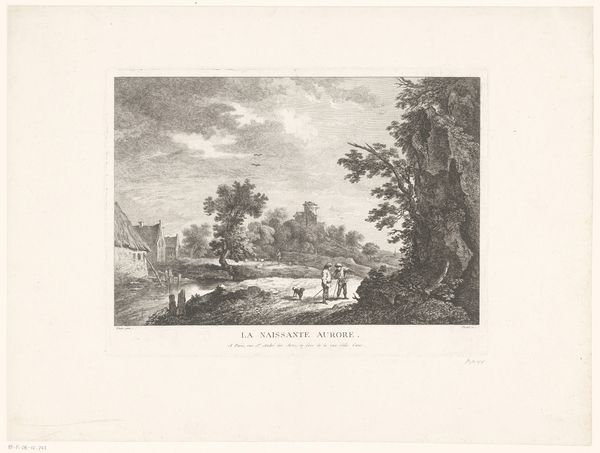

etching, engraving

#

baroque

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

river

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 278 mm, width 320 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jacques Aliamet’s "View of a Village by Moonlight," an etching from 1757 currently held at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you first about this piece? Editor: It’s immediately atmospheric, isn’t it? The tones of gray evoke that liminal space between day and night. The composition seems to emphasize the relationship between the workers in the foreground, nature, and the settlement behind. Curator: Absolutely. It’s interesting to consider how Aliamet uses the etching medium to portray not just the landscape, but also the social realities of the time. This work exemplifies a shift towards genre painting. Look closely. Notice the people engaged in everyday labour near the water. How are gender dynamics reflected? Who are these laborers in relation to their environment? Editor: And the means by which Aliamet achieved these nuanced tonal shifts is noteworthy. The way he works the metal plate – you can almost feel the different pressures he applied to the burin. He isn't just depicting a scene, but demonstrating his command over materials and technique, which makes one think about artistic labor in itself. Curator: It's compelling to examine how Aliamet appropriates existing visual vocabularies to establish certain themes and how the artist may engage with broader ideas regarding the idealization of rural life at the dawn of industrialization. Consider what stories about labor and land ownership the work subtly implies. Editor: Right. Consider the distribution and value attached to copper as raw materials in printmaking, the market for prints in 18th-century Europe, the labor divisions required to produce and sell etchings to emerging urban audiences. Aliamet is not just depicting a view but also embedding material processes of consumption and dissemination within it. Curator: Examining such a pastoral image from an intersectional lens sheds new light on whose perspectives and experiences are often overlooked. Are we, as viewers, positioned as romantic observers, or as implicated members of a more complex system? Editor: This etching speaks to so many layers of reality. Production, labor, atmosphere. It pulls us into considering a slice of 18th-century life, not only in what is shows, but what was necessary for its creation. Curator: Exactly. It offers a contemplative and critical point from which to question art, gender and power. Editor: It has also altered my initial perception, to now understand what Aliamet sought to make visible via craft and process.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.