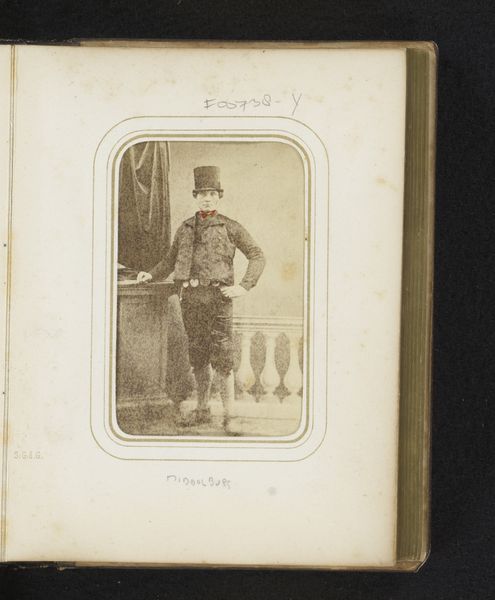

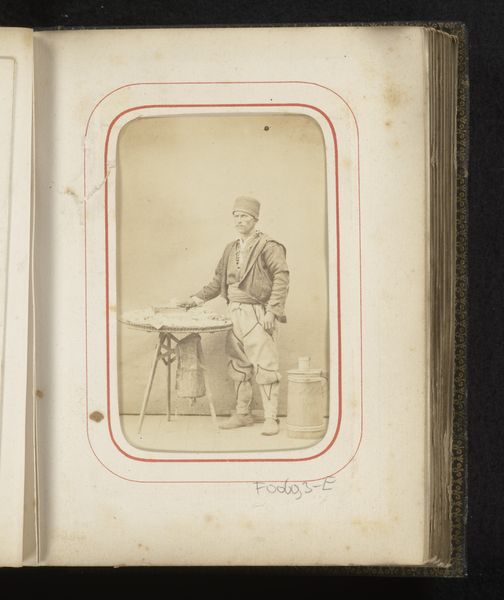

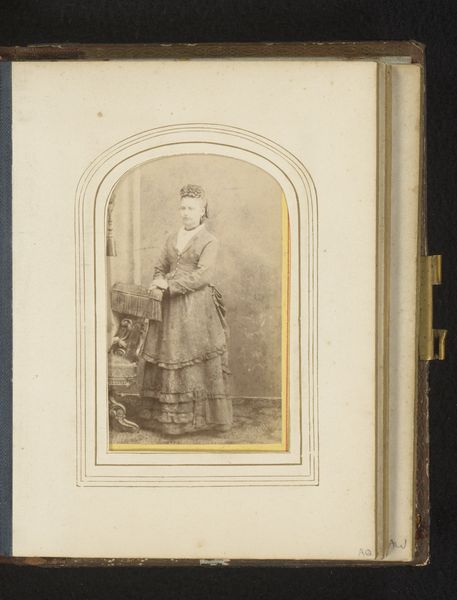

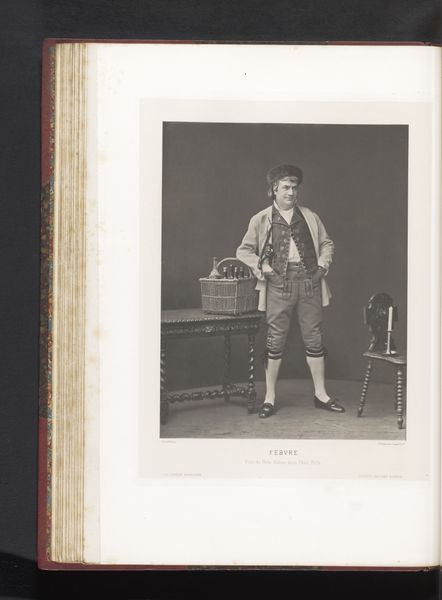

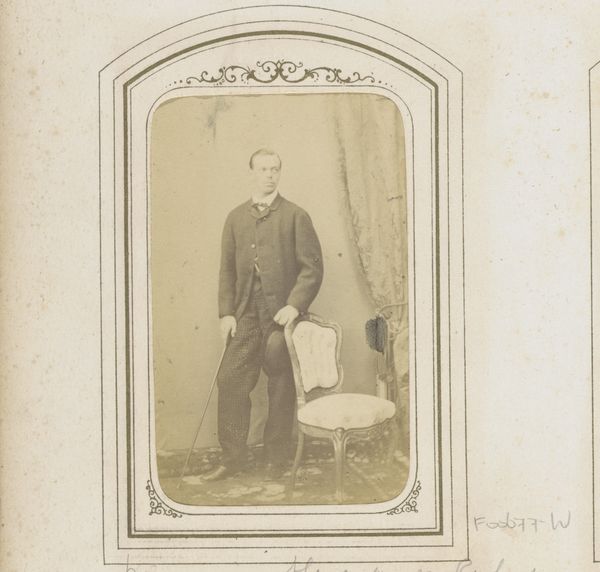

Portret van een man in klederdracht van Middelburg, Zeeland 1860 - 1890

0:00

0:00

andriesjager

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van een man in klederdracht van Middelburg, Zeeland" created sometime between 1860 and 1890 by Andries Jager. It’s a photograph depicting a man in what appears to be traditional clothing. I'm struck by how staged it feels, almost like a theatrical production. What stands out to you? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the materiality of this image. It’s a photograph, yes, but let's consider what that *means* in this period. The collodion process, likely used here, involved skilled labor, specific chemical knowledge, and expensive equipment. This wasn't a snapshot; it was a crafted object. How does that understanding change our perception of the sitter? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t considered the labor involved so directly. It makes me wonder who had access to this kind of portraiture? Curator: Exactly! Think about the social context. Photography, even in its relative infancy, was a commodity. The man is displaying the distinctive clothes of Middelburg; it looks quite elaborate, but who would have the means to both commission a photographic portrait and preserve their regional garb, perhaps even as it was becoming less common in daily life? Was it personal pride or something commissioned? Editor: So, is it less about documenting "real life" and more about presenting a constructed identity tied to material culture? Curator: Precisely! The photograph, through its very making, becomes an active participant in shaping and perhaps even preserving that identity, for the sitter, or possibly for broader civic uses. We must think, how and where was this image circulated? Who handled it? What did they learn from it? Editor: That completely shifts my understanding of the image. I was focusing on the "what," but now I see that the "how" and "why" of its creation are equally important. Curator: Indeed. The materials, the labor, the consumption – they're all integral to the artwork’s meaning, moving beyond surface representation. Editor: Thank you. I’ll definitely keep in mind how the means of production shaped its cultural importance. Curator: It transforms the portrait from a static depiction to a rich record of social practice, hopefully prompting a richer view of cultural meaning as it circulates within different populations, in the past and in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.