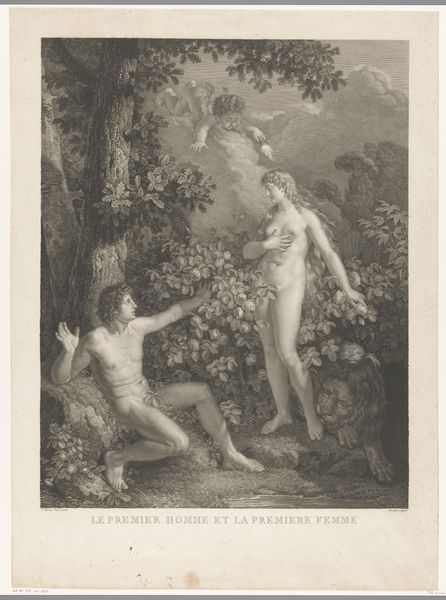

Dimensions: Sheet: 13 1/16 × 10 9/16 in. (33.2 × 26.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

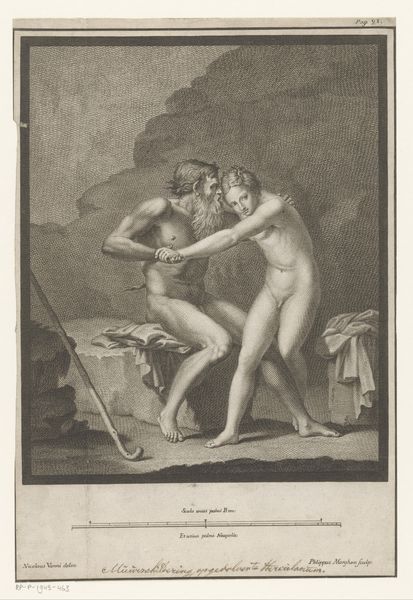

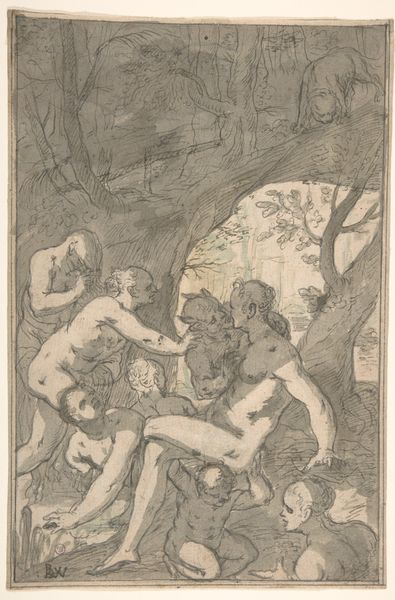

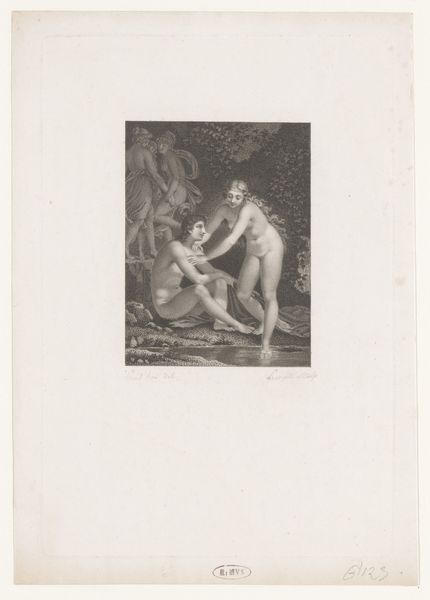

Curator: Here we have "Amymone (?) with a Lecherous Satyr," a watercolor over graphite on paper attributed to William Hamilton, dating from around 1770 to 1780. Editor: Well, that's a title and a half! My first impression is...uncomfortable. The poor woman looks trapped. The muted palette just adds to the oppressive mood, like a humid dream turning sour. Curator: "Uncomfortable" is an apt description. William Hamilton and his contemporaries were fascinated with classical mythology and often explored scenes of violence, seduction, and abduction in their work, frequently sidestepping into some kind of titillation. Representations of women were often caught between allegorical virtue and vulnerable physicality for the male gaze. Editor: It's more than just vulnerability, though. Look at how her pose— ostensibly reaching for the tree for support—actually imprisons her against it. And that satyr's…well, he's not exactly subtle, is he? It feels less like playful myth and more like a stark power dynamic. Curator: Indeed. Satyrs, historically, have represented unbridled, often unwelcome, masculine desire. This drawing likely plays into prevailing notions of female purity being threatened by male lust. Consider the popularity of similar narratives during the period, feeding into a discourse of morality that often policed female bodies. Editor: It is so interesting. And there is something almost naive about its style—a sort of dreamlike remove that belies its grim subject matter. I suppose it reflects the hypocrisies of that moral discourse that you are mentioning... almost as if it is hiding its real meaning behind this pleasant Rococo scenery and erotic mythology. Curator: Absolutely. That tension between outward elegance and underlying darkness is characteristic of the Rococo period, reflecting complex social and cultural currents. Hamilton’s "Amymone" is but one such artifact illustrating our tendency to find erotic power imbalances throughout history, even today. Editor: Gives you a lot to think about when you see art as an object in history... It's not enough to simply admire what is there— you must understand what is absent too. Thank you. Curator: And thank you. Recognizing historical patterns reminds us that the work is always ongoing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.