Copyright: Public domain

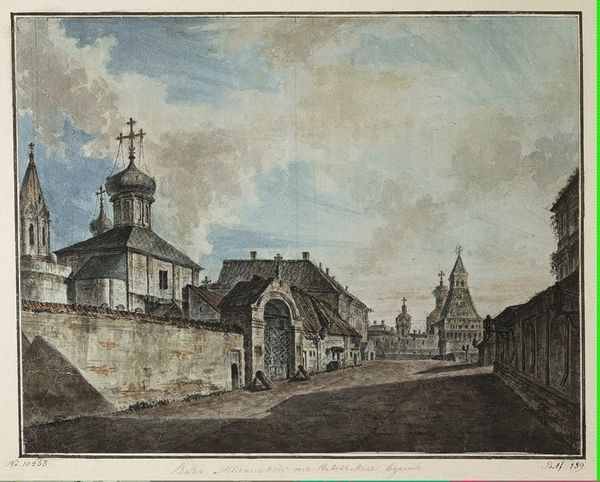

Editor: We're looking at Bernardo Bellotto's "Visitationist Church in Warsaw," painted around 1780 using oil paints. It's a remarkably detailed cityscape. What particularly strikes me is the contrast between the imposing architecture of the church and the everyday life unfolding in the square. What catches your eye in this piece? Curator: I find it fascinating how Bellotto uses the materiality of paint to not just depict, but to almost *construct* this urban space. Notice how the architectural details of the church, achieved through precise brushstrokes and careful layering of pigment, stand in stark contrast to the looser, more gestural treatment of the figures and wagons in the foreground. How does that contrast affect your understanding? Editor: I see what you mean. The church almost feels like a monument, painstakingly rendered, while the people are… well, almost secondary, like props. Does that tell us something about Bellotto's perspective? Curator: Precisely! Consider the context: Bellotto was employed by the Polish King Stanisław August Poniatowski to document Warsaw’s reconstruction. So, while seemingly a straightforward cityscape, the painting becomes a document of labor and patronage. The meticulous rendering of the church – its materials, its construction – speaks to the King's ambitious project of rebuilding Warsaw, showcasing royal power and vision. Editor: So the focus isn’t just on the aesthetic beauty, but also on the means of production and the social implications behind the rebuilding? Curator: Absolutely. Look at the subtle details – the types of wagons, the clothing of the figures. They offer clues about the economy, the social classes, and the labor involved in transforming the city. Bellotto is, in effect, painting a picture of Warsaw's material culture. How does that change how you interpret the figures? Editor: It shifts the focus from them simply existing as a generic crowd, to being part of this economic engine that's visibly rebuilding the city after hardship. It brings another layer to the reading, it feels much richer. Curator: Indeed. The artwork becomes a tableau of production. The relationship between Bellotto, the king, and the city itself all mediated through the application of the paint. Editor: That's a completely different way of considering a seemingly simple cityscape. I hadn't thought about the materiality contributing so significantly to understanding the painting's social and economic context. Curator: And hopefully you will keep questioning the "obvious" meanings moving forward. Every piece is an echo chamber of social practice, of applied effort.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.