photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

academic-art

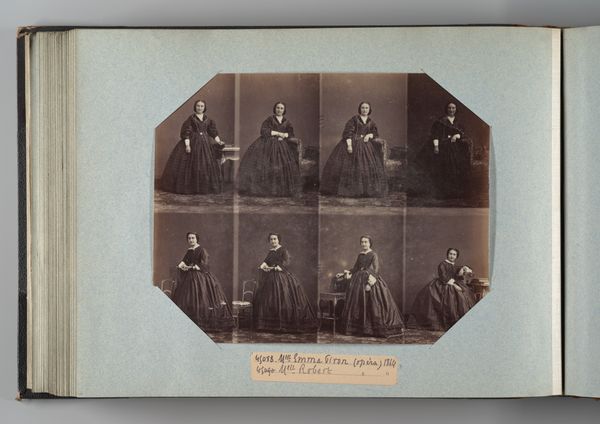

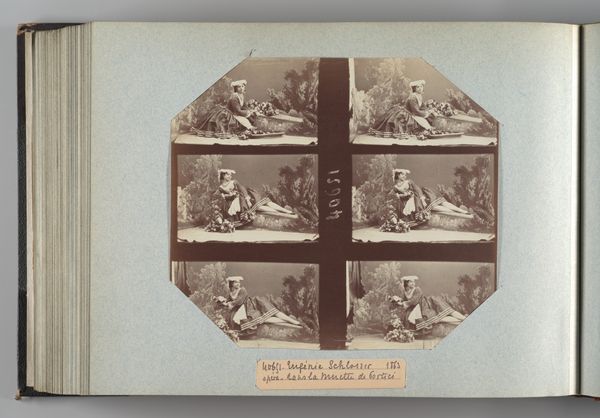

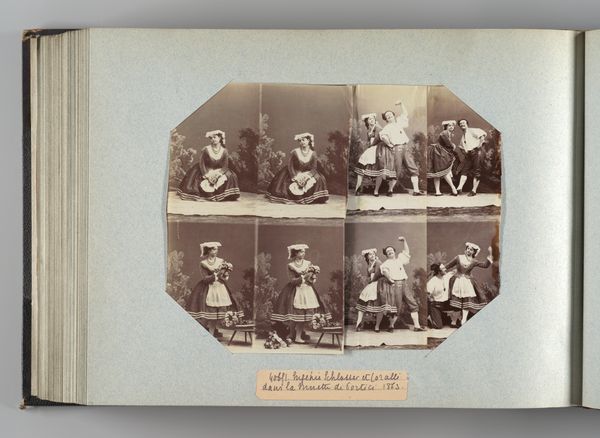

Dimensions: Image: 7 3/8 × 9 1/4 in. (18.8 × 23.5 cm) Album page: 10 3/8 × 13 3/4 in. (26.3 × 35 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri's "Eugénie Schlosser," taken in 1861. It's a photograph, presented in an octagonal format with eight distinct poses. What strikes you about it initially? Editor: My first impression is that it’s…awkwardly charming. She looks utterly pinned in by expectation, a social butterfly preserved in amber. Is this meant to showcase eight facets of her personality, or the constraints she felt compelled to strike? Curator: Precisely. Disdéri patented this method of creating multiple exposures on a single plate. It became enormously popular, particularly for portraits. It democratized image-making, and thus, in a way, power, allowing more people to participate in visual representation. Editor: "Democratized" feels too kind, don't you think? All I see is the visual grammar of status and the burden on her. Each pose looks deliberately designed, offering little that feels authentic. The composition feels very calculated. The drape of her dress. The hand placement...it’s all so stiff. Curator: Well, consider the social context. Photography was relatively new, and portraiture was traditionally the domain of the wealthy. This multi-pose approach made it more accessible. This allowed a wider audience to perform or present an ideal self to the public, which really altered how people perceived each other and celebrity. Editor: Performance, yes. But is accessibility always synonymous with liberation? The gaze feels undeniably controlled, not necessarily empowering. Even her props and flowers feel stagey, like window dressing. I wonder what she thought of it? Curator: An interesting question. It really highlights the tension between technological advancement and individual expression. These types of photographs provided some autonomy, but they were ultimately marketed for status building, memorialization, or relationship-defining milestones like engagements and marriages. Editor: So, in a sense, a powerful commentary on the early commodification of the self? Curator: Absolutely. A snapshot – no pun intended – of social pressures made visible through technological innovation. Editor: Seeing it from that angle adds a layer of melancholic beauty to the stiffness of it all. It’s like finding humanity etched within constraint.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.