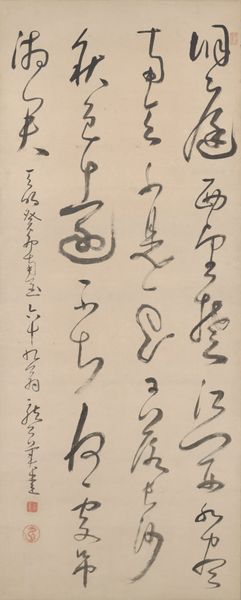

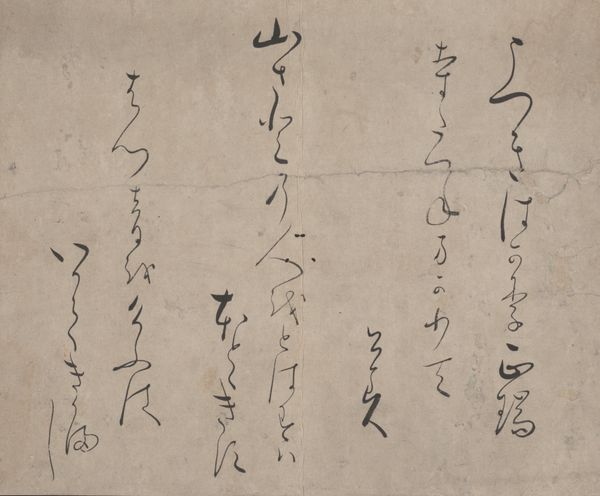

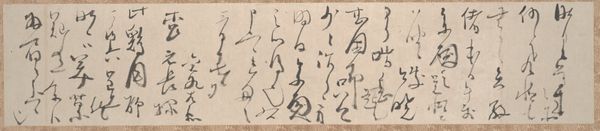

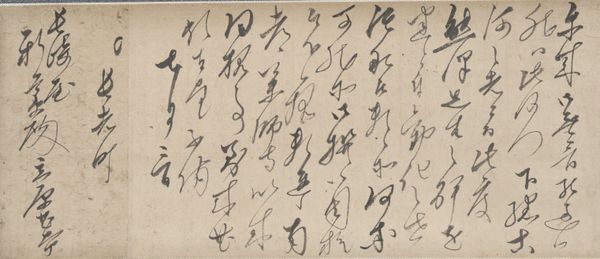

paper, ink

#

asian-art

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphic

#

abstraction

#

line

#

calligraphy

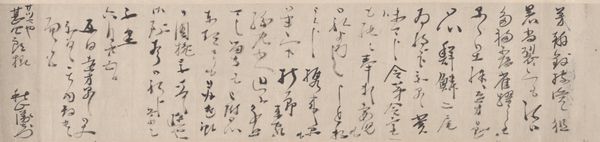

Dimensions: 11 9/16 x 365 3/4 in. (29.37 x 929.01 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

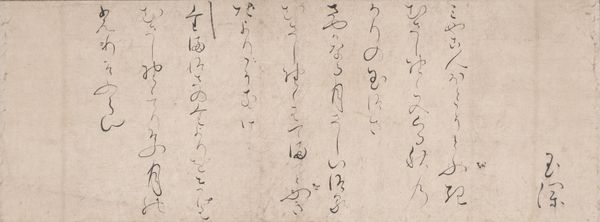

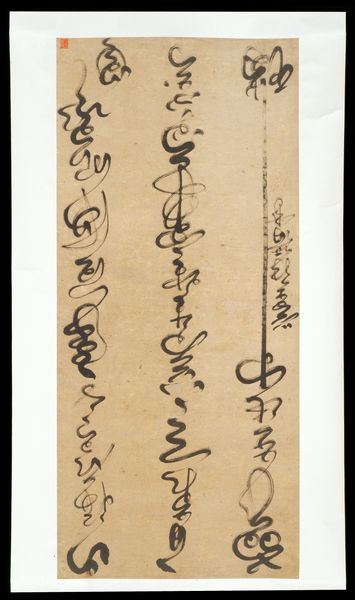

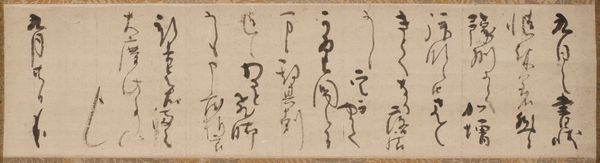

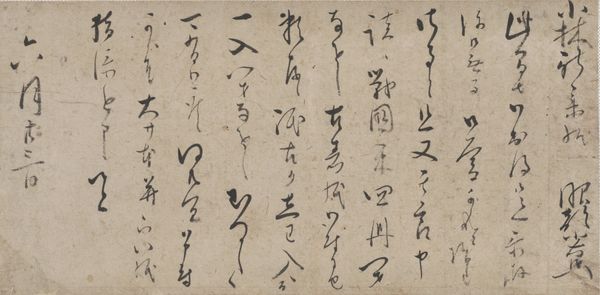

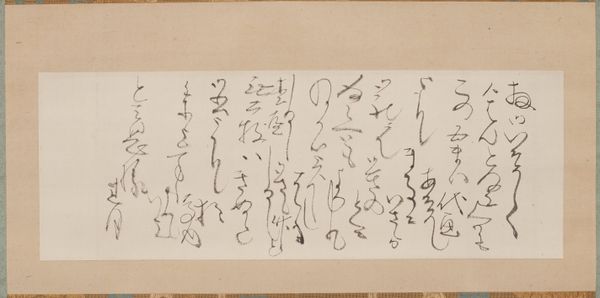

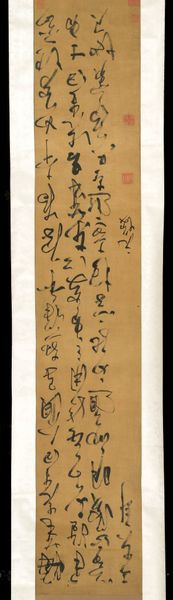

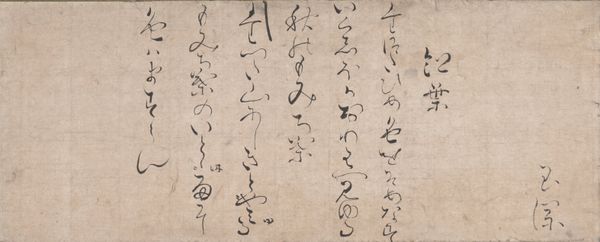

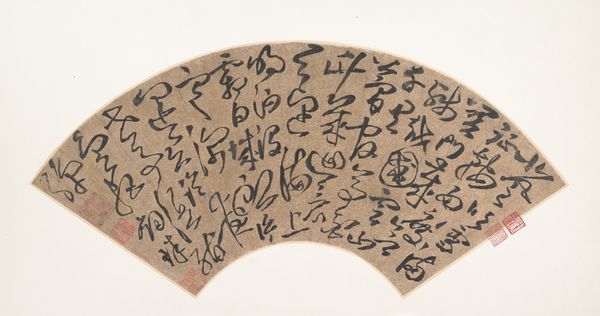

Curator: Standing before us is Chen Chun’s "Three Ancient Poems in Cursive Script," created around 1535. It’s ink on paper and showcases a striking display of calligraphic art. Editor: My initial reaction is one of energy; a chaotic yet strangely balanced energy. The marks feel immediate and improvisational. I imagine the speed and rhythm with which the artist applied the ink. Curator: Absolutely. The dynamism comes from Chen’s masterful handling of line and form. Consider the strategic use of varying line thickness—thick strokes juxtaposed with thin, fleeting gestures. We can really see an artist who is exploring the interplay between intention and accident in his aesthetic structure. Editor: I agree; but beyond aesthetic play, think about the actual labor invested here, the hours spent mastering the brush, mixing the ink, and selecting the paper, which also suggests certain resources that were readily available for the making. What was the socio-economic reality enabling these daily practices? Curator: An interesting point, given the materiality involved, yet this work really emphasizes the symbolic value of writing and erudition. It embodies literati ideals by elevating calligraphic gestures. The composition shows a sophisticated arrangement within each panel that speaks to principles of balance, rhythm, and negative space. Editor: Balance perhaps, but I see an active resistance against notions of preciousness and control. Ink splatter seems purposefully left—an index of the material reality of the writing. Consider also, how Chen may have used locally sourced materials. Curator: Still, that doesn’t detract from the elegant, refined execution we observe, particularly within each panel. The poems aren’t merely written; they are visually composed—each stroke contributes to an overall visual harmony, revealing internal semiotic logics, if we know the codes of translation. Editor: Perhaps. For me, that visual harmony underscores the social functions tied to this artifact. Calligraphy was deeply entangled with ideas of authority, with the circulation of bureaucratic and administrative power at that moment in China’s cultural production. Curator: It has certainly given us plenty to consider in terms of formal arrangement, symbolism, and also materiality. Editor: Indeed, from the artist’s tools to its connection to greater power structures, this piece is rich in possibilities.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Chen Chun, one of the most important Ming dynasty calligraphers and flower painters, was born into a modestly prosperous literati family. His first teacher was the great literatus, Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), and between 1519 and 1523 he studied at the Imperial Academy in Beijing. While initially influenced by the writing style of Wen Zhengming, Chen quickly developed a personal approach based more on the calligraphy of the ancient masters Mi Fu (1051-1107) and Yang Ningshi (873-954). His running and cursive scripts (Cao-shu) for which he is most famous display characteristic fluidity, boldness, and exuberance. The frontispiece to the handscroll is written by Chen's friend and teacher Wen Zhengming, leader of the Wu school. Wen's four-character title reads:Pai Yang (Chen Chun) the sage of cursive scriptIn these three ancient poems Chen writes with the exuberant fluidity that made him, along with Zhu Yunming (1461-1527) and Wen Zhengming, one of the most important Ming masters of Cao-shu script.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.