#

charcoal drawing

#

possibly oil pastel

#

charcoal art

#

oil painting

#

acrylic on canvas

#

underpainting

#

mythology

#

human

#

painting painterly

#

portrait art

#

watercolor

#

digital portrait

Copyright: Public domain

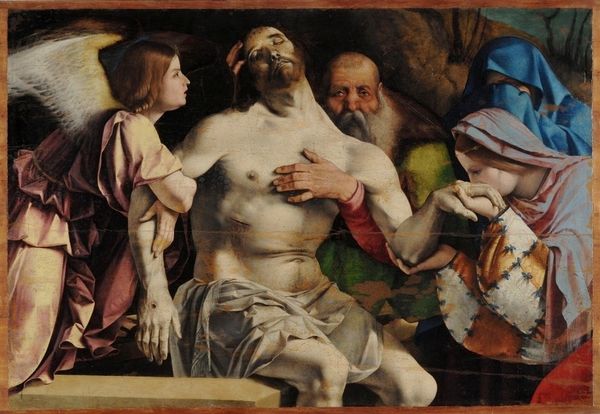

Curator: Giulio Clovio, circa 1550, gave us this deeply moving depiction of the Pietà. What's your immediate reaction to this work? Editor: A profound sense of stillness and sorrow. The muted colors and slumped figures evoke a heavy atmosphere of loss, don't they? The almost corpse-like pallor of Christ is especially affecting. Curator: Indeed. And let’s consider the historical backdrop: Clovio was working in a time of tremendous religious upheaval, the Counter-Reformation. Depictions of Christ’s suffering and the Virgin Mary’s grief served to reinforce core Catholic values in the face of Protestant challenges. How do you feel that sociopolitical pressure influenced this work, beyond the thematic subject matter? Editor: Certainly, there’s an overt promotion of the emotional core of Catholic doctrine through this scene. Yet I see something more universal at play. Consider how vulnerability is expressed: we see pain, powerlessness, shared grief. This challenges the stereotypical hyper-masculine presentations often attributed to the period and calls for a rethinking of dominant gender roles within the Passion narrative. What do you make of it? Curator: That's a fascinating interpretation. While art history situates this as part of a visual strategy promoting Catholic doctrine in the period, its wider significance stems from an appeal to universally recognizable emotions around death. Note the figures around Christ and the Virgin; are these Mary Magdalene, Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea? The artist crafts not just religious icons, but witnesses who represent humanity collectively in mourning. Editor: I concur, yet wouldn’t you agree that it’s nearly impossible to see such deeply embedded iconography independent of a feminist reading? How do the expressions of those witnessing relate to an interrogation of mourning beyond patriarchal power dynamics? I think these expressions are equally powerful because the viewer too can become implicated in these moments. Curator: An essential point. And Clovio succeeds so powerfully precisely by leaving the viewer unsettled, implicated in a social and spiritual tragedy played out on a grand, universal scale. The artist’s decision to include additional witnesses at the scene complicates an understanding of both art-making and emotional engagement in the Renaissance period. Editor: Exactly. “Pietà” offers us more than just a glimpse into sixteenth-century art, culture, or religious contexts: the artwork compels us to consider questions of human anguish from perpetually new angles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.