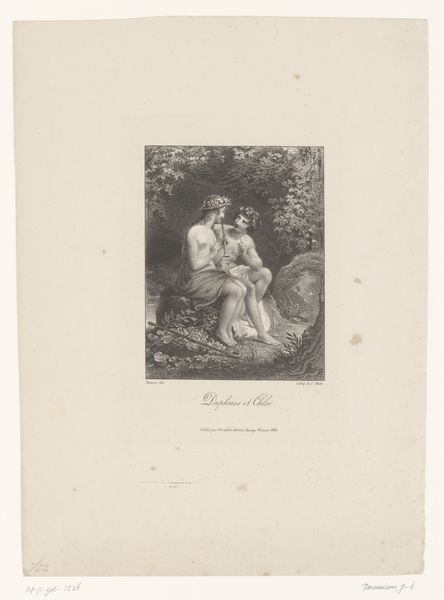

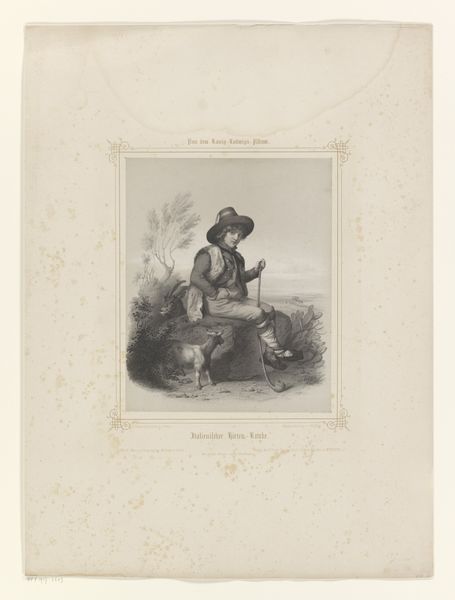

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

archive photography

#

romanticism

#

mountain

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 447 mm, width 307 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

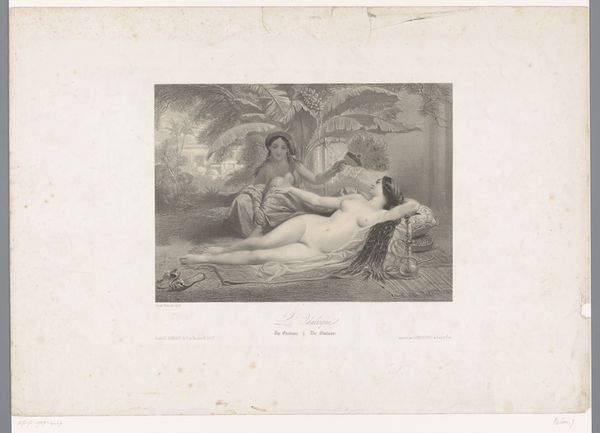

Curator: Émilien Desmaisons' "Herderin met geit opgeschrikt door wolven," dating from between 1838 and 1842, presents a dramatic landscape with a shepherdess at its center. At first glance, the subdued tones of this engraving conjure a quiet pastoral scene shattered by impending danger. Editor: You're right about that shattering feeling. The body language of the figures tells a lot: the frantic energy really surges through me, like a memory—though, of course, of something I’ve never actually experienced. But, I mean, she's clutching that goat as if her life depends on it, staring into an unseen terror! Curator: Absolutely, and it is that sense of imminence that encapsulates much of what Romanticism was exploring then. Let's talk about how this print engages with materiality. As an engraving, each line is etched deliberately. You can see the artist took great care to vary line weights and densities, to create both the sense of depth within the mountainous setting, but also, to accentuate our character's palpable fear. Editor: I think it really spotlights a particular socioeconomic divide. Desmaisons, whose engravings were popular enough to be at the Rijksmuseum, would have, with relative certainty, been completely distanced from the circumstances of that poor, probably starving woman. Consider how those landscapes actually represent a specific mode of working in the 1840s, that required particular technologies and distribution networks. Curator: And it's intriguing, this representation of the “pastoral ideal" is framed, quite literally here, with shadows and looming threats of nature, right? Not exactly selling this way of life. It reminds me how our own fears of loss, of vulnerability, are as old as hills, if not as these engraves, perhaps! Editor: Right, because who is to say how much his art was, was genuinely interested in understanding these women? He’s packaging something consumable. These images helped to solidify both a specific version of this figure, this rural labourer, whilst furthering his own position in this rapidly developing economy and material mode. Curator: It definitely gives you something to chew on, and speaks volumes about storytelling, survival, and, dare I say it, even… goats? Editor: Ha! Yes, even goats. A print like this throws into relief the uneasy relationship between art, labor, and consumption. The art object’s material, its production process—these aspects aren't just aesthetic considerations, they also offer powerful social commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.