painting, oil-paint

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

fruit

#

russian-avant-garde

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

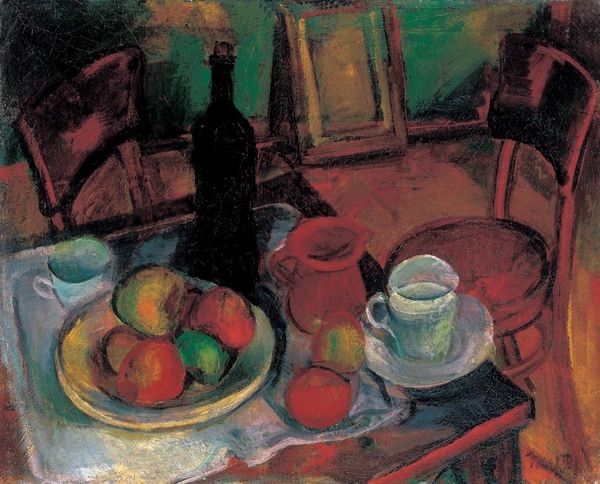

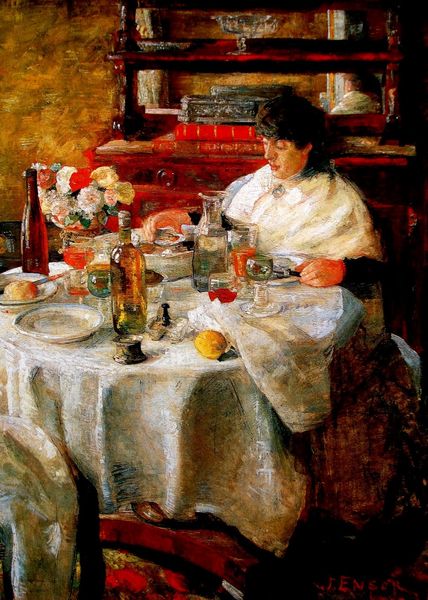

Curator: Let’s explore Konstantin Egorovich Makovsky's "Still Life in an Interior," an oil painting from around 1900. Editor: It’s quite lovely, almost overwhelmingly domestic. The deep green walls, the polished silver tea set, that plush red chair… it feels like a stage set for a late afternoon tea party. Curator: Precisely! The objects themselves, though seemingly ordinary, speak volumes about class and gender roles within Tsarist Russia. Silverware and delicate china signal wealth and the rituals of the bourgeoisie, specifically, domestic rituals maintained largely by women. Editor: Yes, the sheer accumulation of objects is significant. All these materials—the silver, the oil paint, the presumably imported fruit—had to be extracted, processed, and transported. Where were those production sites? Who labored? I wonder about the lives intertwined in the making of such opulence. Curator: Absolutely, examining the modes of production is key. Furthermore, note how the realism of the painting actually obscures those very conditions. Makovsky presents a sanitized view of upper-class life, deliberately avoiding any portrayal of the exploitation necessary to sustain it. The viewer is invited into a carefully constructed illusion. Editor: An illusion reinforced by the materiality of paint itself. Look at the texture – those thick impasto brushstrokes on the tablecloth! It almost feels edible, yet also distances us from the actual textile and its manufacturing process. The chair’s upholstery mirrors that disconnect, doesn't it? Curator: Definitely. And thinking about that textile production… the dyes alone required extensive, often dangerous, labor to produce. Even something as simple as the white tablecloth represents the culmination of multiple, interwoven power dynamics. It silently speaks to the economics of colonialism and its inherent injustices. Editor: The painting then becomes more than just a depiction of objects; it’s a material record, subtly hinting at its own construction. And not just the artist's labor, but also the labor embodied by everything inside the picture. I feel I understand how luxury functions much better now. Curator: Exactly! Makovsky inadvertently invites us to question the unseen networks supporting such curated domestic spaces. That initial impression of charming tranquility gives way to a far more critical, and necessary, line of inquiry.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.