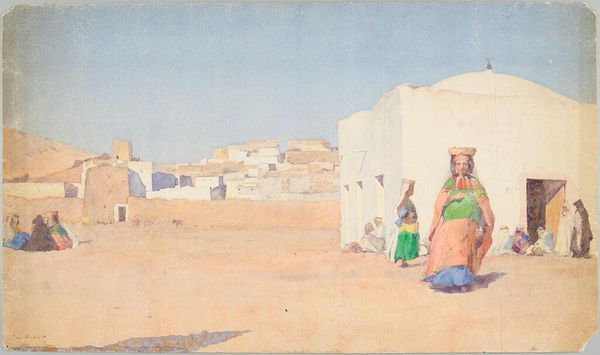

painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

landscape

#

painted

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

orientalism

#

islamic-art

#

watercolour illustration

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

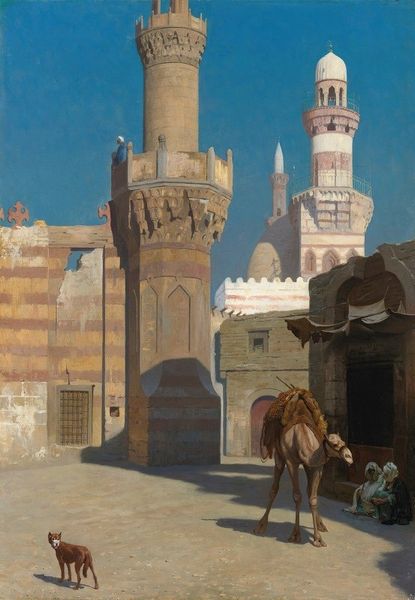

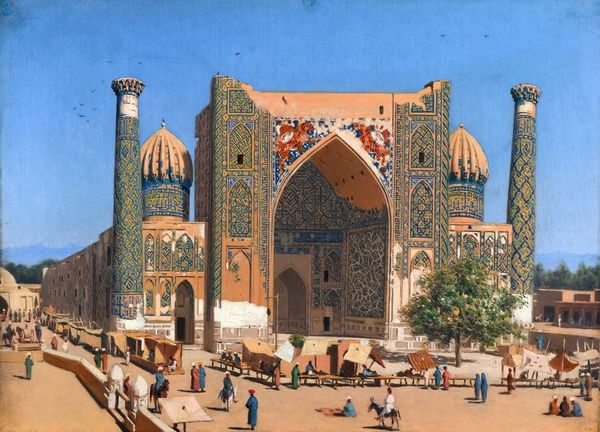

Curator: Vasily Vereshchagin's rendering of the Shah-i-Zinda Mausoleum in Samarkand, dating from 1869 to 1870, strikes me with its seemingly impossible clarity against that almost aggressively blue sky. Editor: I'm drawn to the textures. The way the watercolor and oil evoke the rough, sun-baked surfaces of the buildings and the dusty landscape—you can almost feel the grit. I'm also curious about Vereshchagin's choice to combine these two mediums. Was he perhaps experimenting with ways to depict light and atmosphere with greater nuance? Curator: I think the use of watercolor here tells a compelling story about Orientalism and the ethnographic impulse embedded in much 19th-century art. The presumed accuracy of watercolor lent itself to the depiction of "exotic" locales with an air of objective documentation for Western audiences hungry for imagery from far-off lands. Editor: Absolutely. The material choices play a part in shaping our understanding. And those choices, in turn, affect the reception of the work by different publics. Did his audiences recognize, say, the artistry of the ceramic tilework? Was it framed, instead, as merely representative of the 'East'? The unevenness of the structures suggests natural decay as much as it does hand-craftsmanship. Curator: It’s certainly something to consider. Also the institutional framework that sustained artists like Vereshchagin through patronage and exhibition opportunities helped determine what aspects of a place like Samarkand would be amplified or muted in their paintings, constructing a very specific narrative around power dynamics, and exoticism. The perspective gives prominence to the decay. Editor: Precisely. And yet, you have to admire the detail of Vereshchagin's labor in capturing each eroded surface and bit of intricate tilework. The sheer investment of time and material resources into creating this image is considerable. It shows Vereshchagin was involved in the materiality and process of documenting a place with great attention to its visual details. Curator: Indeed, so perhaps it becomes an active part of this broader discourse on representation and the mediation of cultural encounters within unequal power structures of the era. Editor: Yes. I leave with a greater appreciation of art's capacity to document places as well as the layered contexts that art and the act of making introduce to historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.