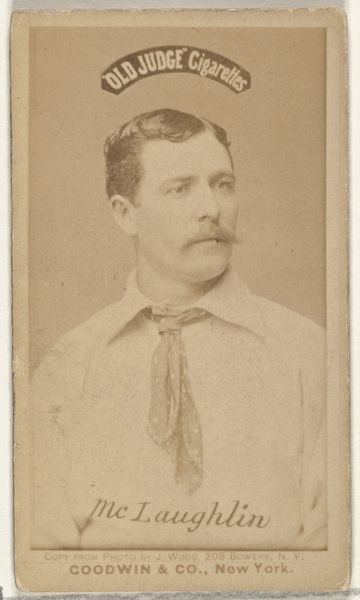

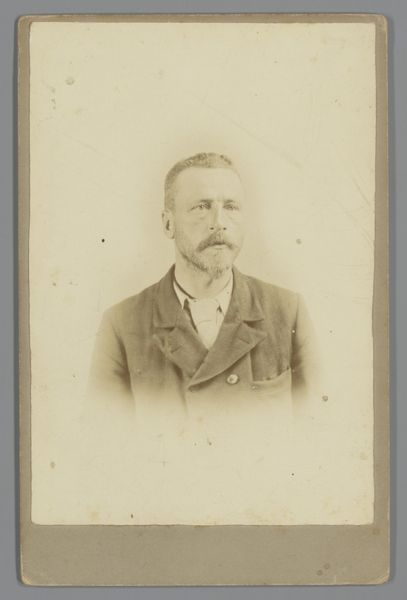

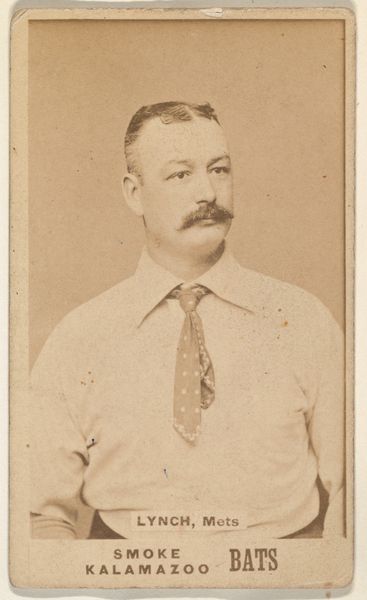

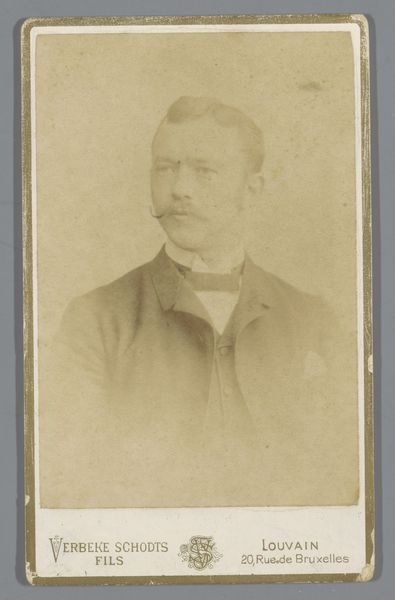

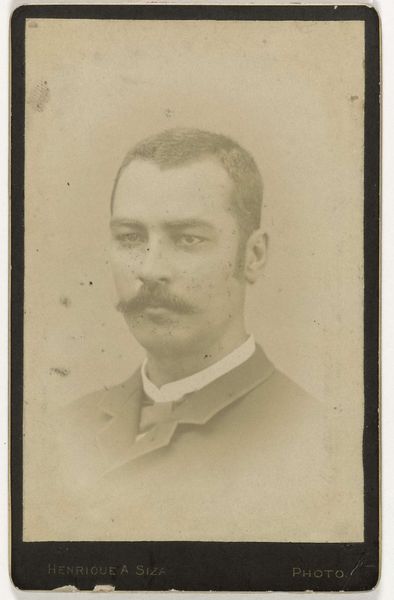

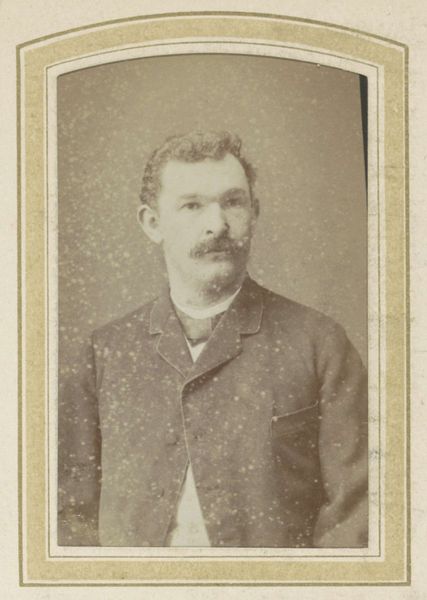

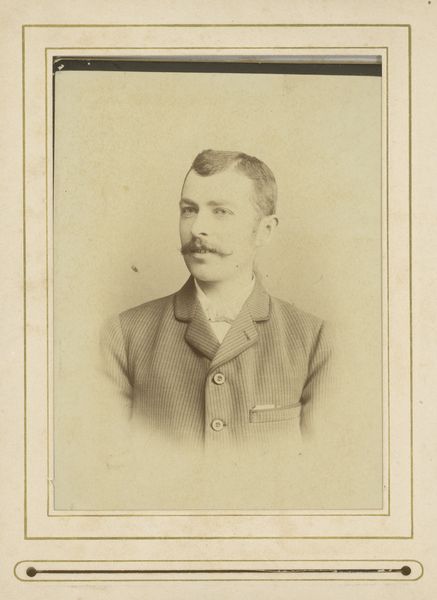

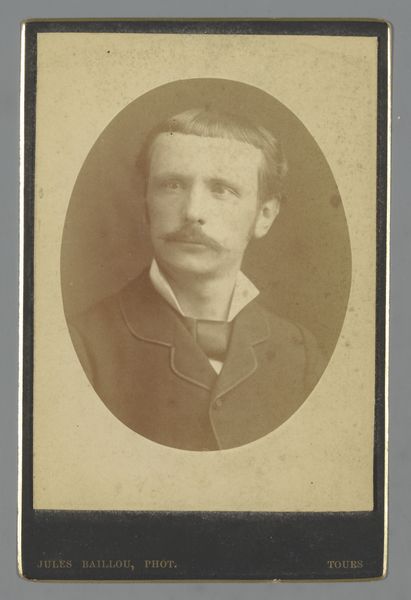

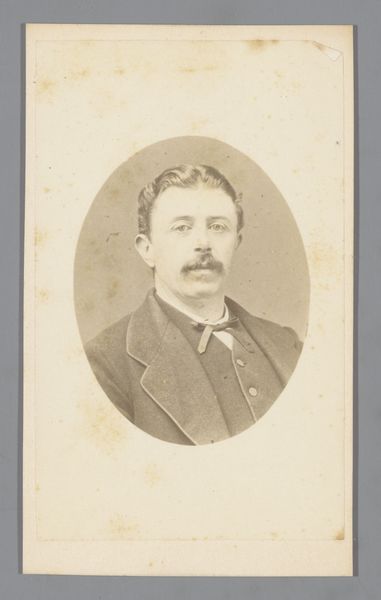

Mangin. Edmond, Émile. 33 ans, né le 19/3/61 à Senon (Meuse). Cimentier. Anarchiste. 8/7/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

men

#

academic-art

#

poster

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Mangin. Edmond, Émile. 33 ans, né le 19/3/61 à Senon (Meuse). Cimentier. Anarchiste. 8/7/94," a gelatin-silver print from 1894 attributed to Alphonse Bertillon and held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s incredibly haunting, this straightforward mugshot. There’s a weight in his gaze, a weariness. I can’t help but wonder what brought him to this point. Curator: Bertillon, of course, was instrumental in developing anthropometry—a system used for criminal identification. This photograph is a potent example of how science and law enforcement intersected in late 19th-century France, solidifying societal biases. Editor: Absolutely. The stark presentation – the flat lighting, the frontal pose – strips Edmond of any individual narrative, reducing him to a set of measurable traits categorized for bureaucratic control. Even the inscription naming his profession is weaponized. Curator: The inscription is particularly telling. The inclusion of “Anarchiste” marks him not just as a criminal, but as a political threat during a period of significant social and political unrest. His working-class identity as a "Cimentier" further complicates the narrative when understood alongside the socio-economic tensions in French society. Editor: It speaks volumes about who had power and who didn’t. And it makes me consider how such images helped construct public perception of anarchist figures, cementing fear and prejudice in popular imagination. Were these 'scientific' endeavors objective, or did they contribute to a dangerous social othering? Curator: The latter, most certainly. Photography, then considered objective, reinforced those classifications and allowed these ideas to spread with unprecedented speed and apparent veracity, effectively justifying political repression under the guise of scientific truth. Editor: It's chilling to consider the implications, especially when we consider analogous phenomena in our own contemporary moment. An image like this makes clear the ever-present need to examine power, surveillance, and the stories that images can unintentionally tell—or deliberately hide. Curator: Precisely. Examining these historical records through an intersectional lens provides critical insight into how identity, class, and political affiliations are constantly negotiated, shaped, and regulated by social and institutional power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.