graphic-art, lithograph, print

#

graphic-art

#

aged paper

#

lithograph

# print

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

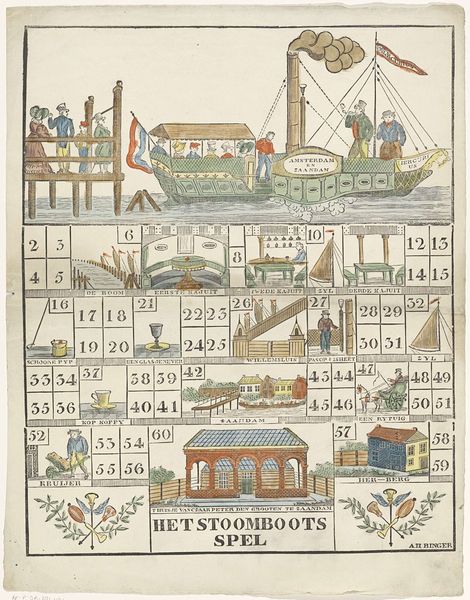

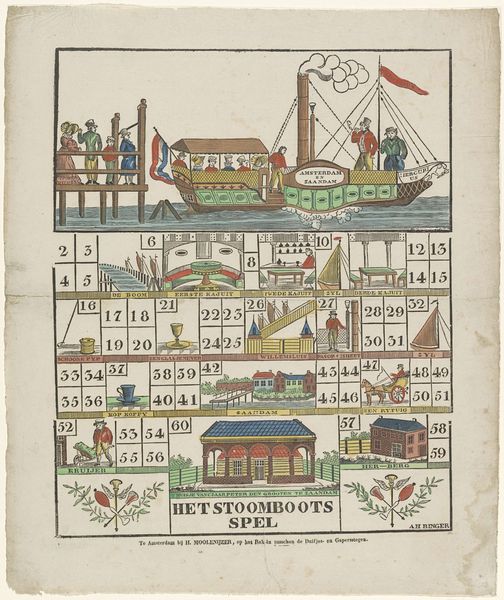

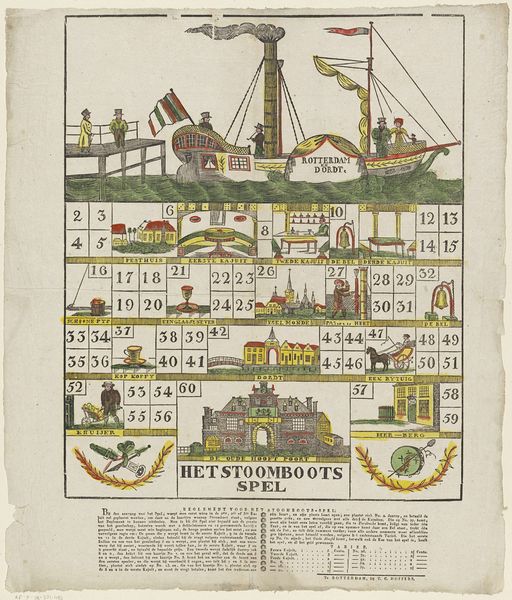

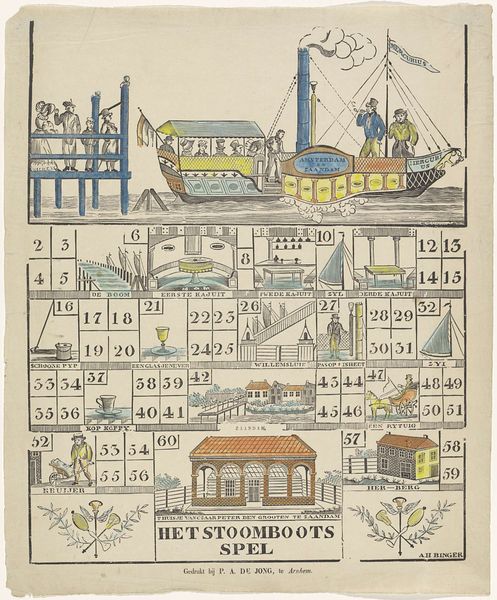

Dimensions: height 500 mm, width 391 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

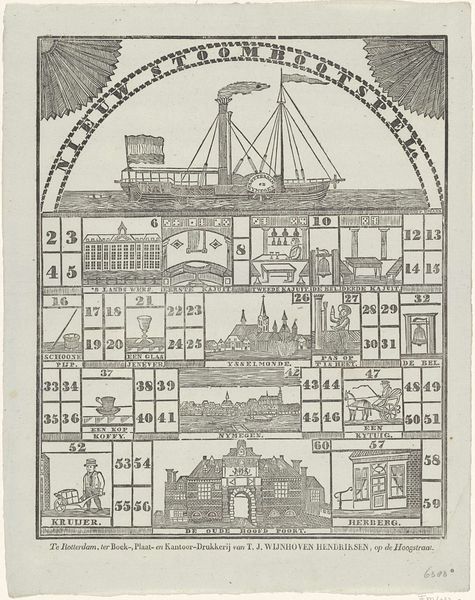

Curator: This whimsical lithograph, "Het Stoomboots / spel," or "The Steamboat Game," dates to around 1850 and is attributed to Aron Hijman Binger. Editor: My first thought is "playful." The soft colours, the way the scene is broken up into these little vignettes... it's like looking at a children's book illustration. Curator: It is quite charming, isn't it? What we're seeing is essentially a board game depicted within the lithograph itself. Each numbered square represents a stage or event in a steamboat journey, offering a glimpse into the culture of leisure and travel in the mid-19th century Netherlands. Editor: Ah, I see now. Looking closer, the scenes—cabins, glimpses of the shore, passengers disembarking—speak to the emerging middle class and their access to these new forms of transport. But the material itself, the lithograph, that's important. It suggests mass production, a wider availability of imagery to people. Curator: Precisely. Lithography allowed for relatively inexpensive reproductions, spreading ideas and representations of modernity, like the steamboat itself, to a broader audience. And notice how the "Amsterdam Zaandam" is painted on the boat itself, which might be referencing to the boat lines and how important they were to Amsterdam and Zaandam trade and communication. Editor: And what's the steamboat made of? The steam billowing out of its pipe suggests industrial might, while the decorative touches hint at a burgeoning consumer culture, doesn’t it? Who were the consumers for this image? I wonder how the experience of "playing" this game shaped their understanding of industry and progress? Was it intended as an educational tool? Curator: That's a key question. Whether purely for amusement or with a didactic aim, this work gives us insights into how the rapidly changing world was being perceived and negotiated by ordinary people. It’s also worth noting how visual and material culture in the nineteenth century supported, critiqued, or resisted dominant political ideologies of the time. Editor: Indeed. And thinking about materiality helps connect what might otherwise be read as quaint images to the industrial engines and social structures that powered the world they represent. I guess these small images can hold very big stories. Curator: Absolutely, it allows us to think through this playful, mass-produced artwork and imagine the society of that era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.