Copyright: Public Domain

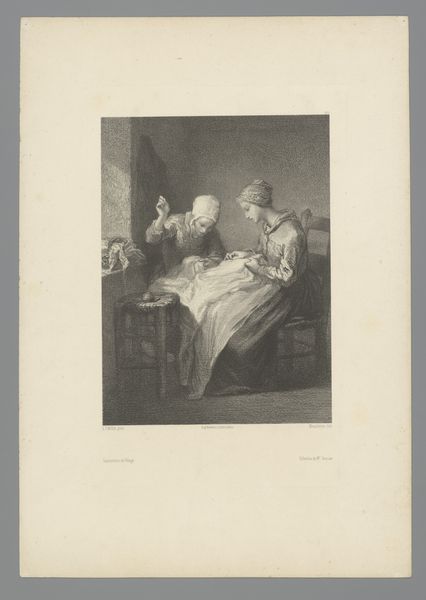

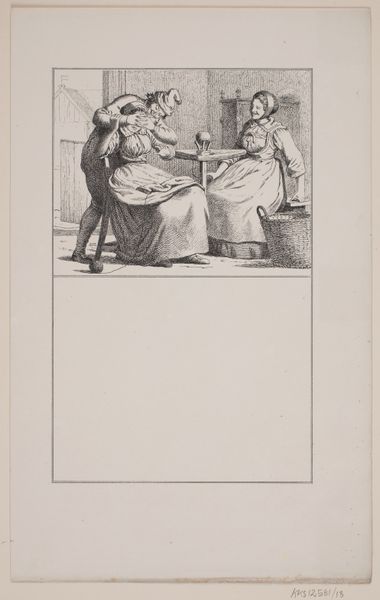

Curator: Jean-François Millet’s “The Village Dressmakers,” likely created between 1835 and 1900, offers a glimpse into the domestic sphere of labor through an engraving on paper. Editor: The somber tones create such an atmosphere, wouldn’t you say? A certain quiet determination pervades. It speaks to the realities, the working conditions of these women... Curator: Absolutely. Note how Millet’s realism focuses on their roles. It highlights their contributions to a burgeoning economic system at the turn of the century. Were they adequately compensated? That’s an intersection of gender and economic agency which deserves scrutiny. Editor: The way the artist uses line and shadow is fascinating. Observe how the light falls on the fabric; that’s not simply visual. It is meant to indicate the painstaking detail required in their craft. Engraving allowed for mass production. Who was going to buy them? Curator: Considering the genre, we can't forget to examine the narratives inherent in portraying working-class women. We see echoes of similar images being disseminated across Europe in other countries as well, often through prints. These prints shaped the narrative about them. Were they a form of subjugation of female agency? Editor: We cannot also simply see them as simply passive recipients in an unjust economic arrangement. Look at how their physical gestures illustrate collaboration. Perhaps through this work, the artisan can achieve a degree of self-autonomy that wasn’t granted any other way? Curator: Perhaps this artwork invites a necessary re-examination of their role. It's more nuanced, though it is not unproblematic, of course. Editor: Looking closely has really opened up new ways of considering the nature of working women. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.