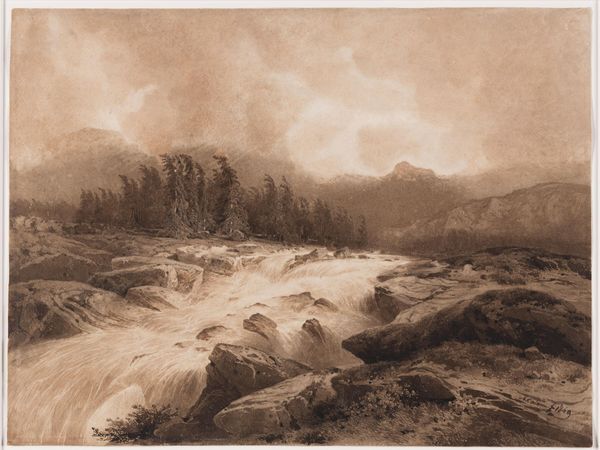

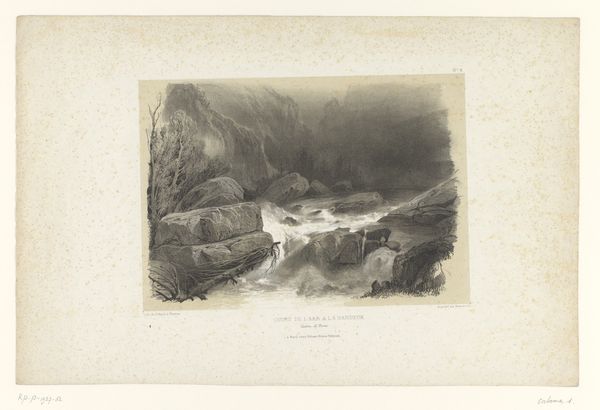

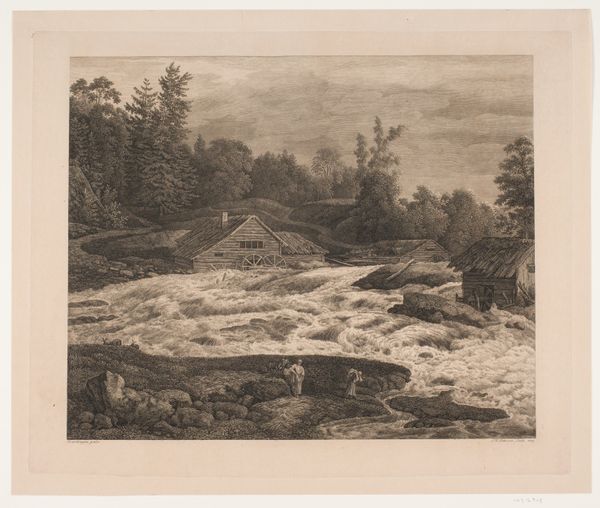

Dimensions: height 401 mm, width 517 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Alexandre Calame’s “Bergbeek in de Hautes-Alpes,” created between 1842 and 1863, using pencil, watercolor, tempera, drawing, and etching. The roaring water gives a palpable sense of nature's power. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see the embodiment of the sublime, the romantic ideal of nature as both awe-inspiring and terrifying. The cascading water, almost overwhelming in its energy, echoes the psychological turbulence explored by Romantic artists. Consider how the mountain, shrouded in mist, serves as a recurring symbol of transcendence. Do you notice the sharp contrast between the untamed torrent and the stoic rocks? Editor: Yes, the rocks provide a solid grounding amidst all the movement. It seems intentional, as if representing stability in a changing world. Curator: Precisely. That interplay speaks volumes. Think of how water often signifies purification, the cyclical nature of life, whereas rocks often symbolize enduring strength and time, which brings forth questions of existential concerns about humanity's place within it all. Also, what of the forest receding in the distance? It seems to hint at mystery, an unknown just beyond our grasp. Editor: I hadn't considered the forest in that way, but it makes perfect sense given the other symbolism present. Curator: This era yearned to connect to nature, viewing it as an untainted source of spiritual truth. Editor: It's fascinating how many layers of meaning can be found in what appears to be a simple landscape. Curator: Indeed! Calame invites us to delve deeper into our understanding of cultural memory tied to visual symbols. It reminds me of our place in time and our responsibility toward nature's bounty. Editor: Thanks for sharing those insights. It’s been very insightful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.