painting

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

painting

#

men

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. (364 x 260 mm)

Copyright: Public Domain

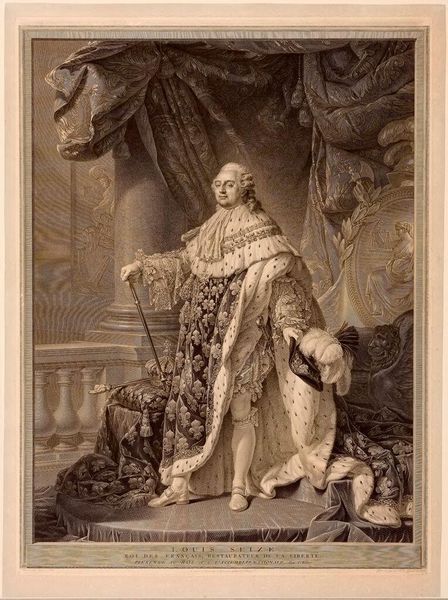

Editor: So, here we have Henry Bone's "Charles X, King of France, after Gérard," painted in 1829. It strikes me as…well, overtly royal. What symbols jump out at you? Curator: The symbols practically shout, don't they? Consider the lion-headed throne – a direct connection to regality, power, and perhaps even divine right. But it's the scepter, the crown, the ermine-trimmed robes – these aren't just emblems of status; they’re carefully chosen devices of a restored Bourbon monarchy seeking to re-establish its cultural legitimacy after years of revolution and empire. Editor: Restored, yes! It feels like Charles X is consciously trying to appear strong and legitimate. How would this image play into that goal? Curator: Indeed. Bone, through Gérard's image, aims to anchor Charles within a visual language of power. Ask yourself, what did French citizens associate with this kind of representation? It's a calculated appeal to a specific memory, and simultaneously, a desire to shape a new one. Consider the echoes of Louis XIV, the Sun King, in the overall composition. It is no coincidence. Editor: That makes so much sense! So, it’s less about an individual portrait, and more about continuing a specific image of the monarchy? Curator: Precisely. Every element carries meaning, designed to evoke a sense of continuity, tradition, and divinely ordained rule. Do you think it resonated with the public at the time, given the shifting political landscape? Editor: Probably not, knowing a bit of French history, which perhaps is what makes the symbolism even more pointed and deliberate. Curator: It certainly adds layers to its interpretation. Symbols never exist in a vacuum; they're always in dialogue with their historical context and the cultural memory they attempt to manipulate. Editor: I’ll definitely look at portraiture differently now, thinking about the memory that the symbolism carries within it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.