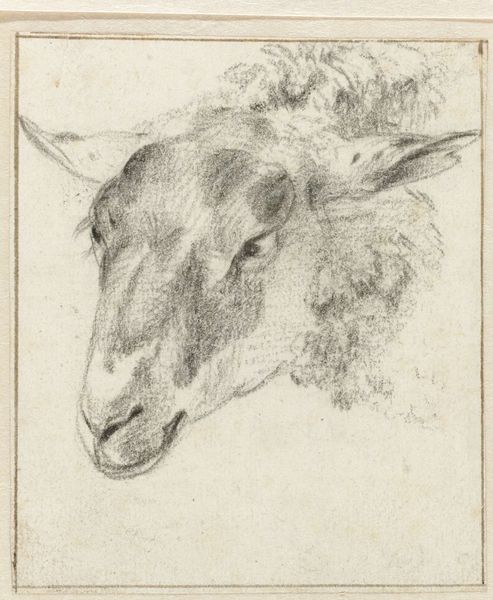

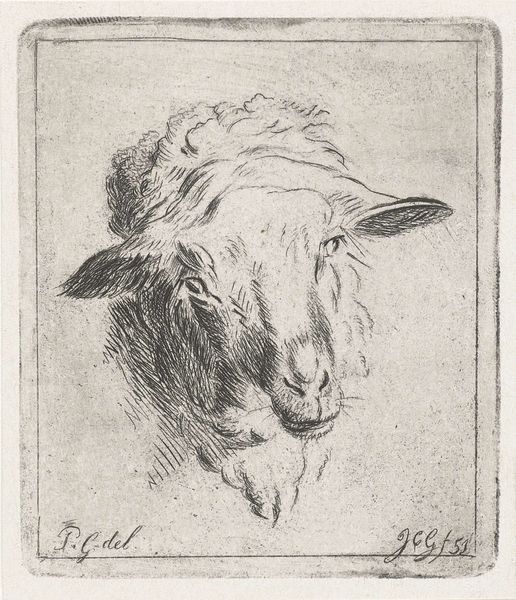

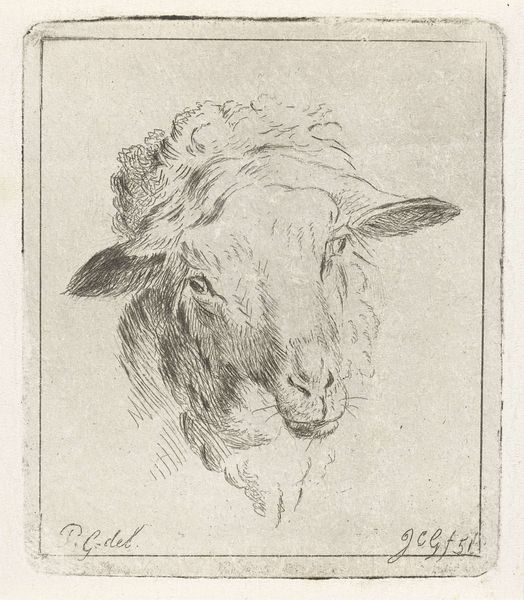

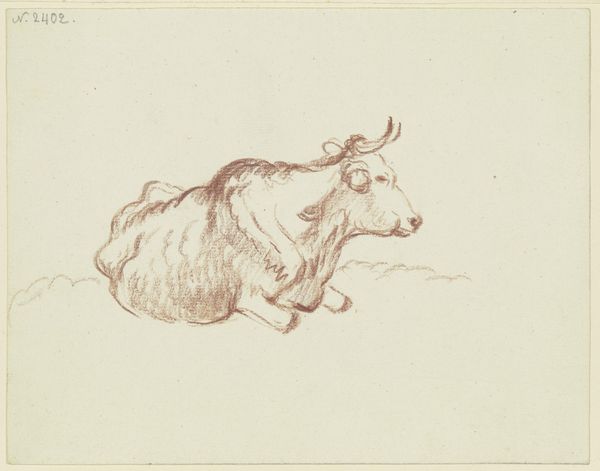

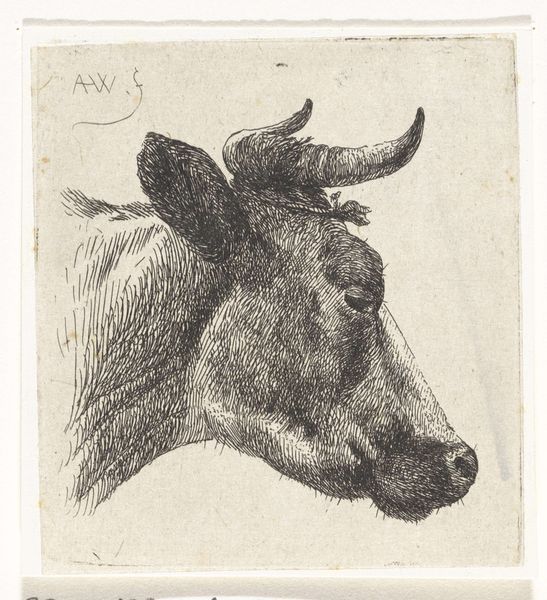

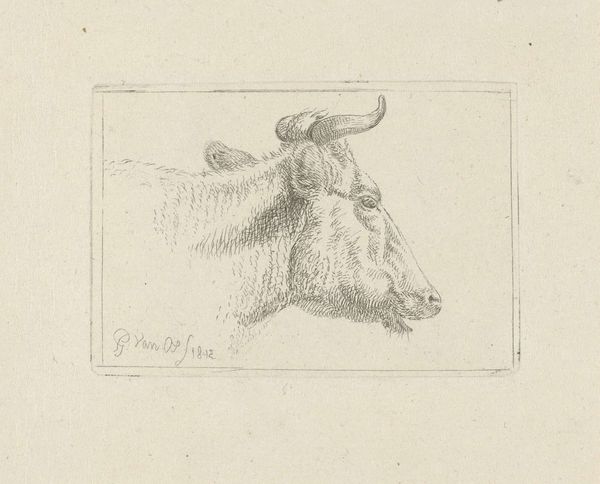

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

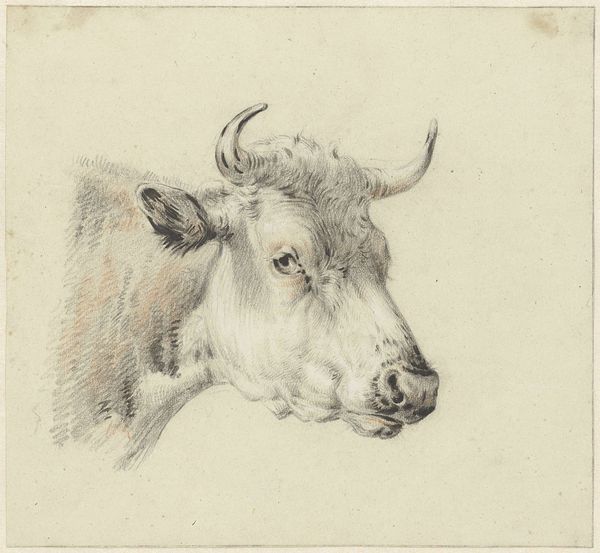

drawing

#

ink drawing

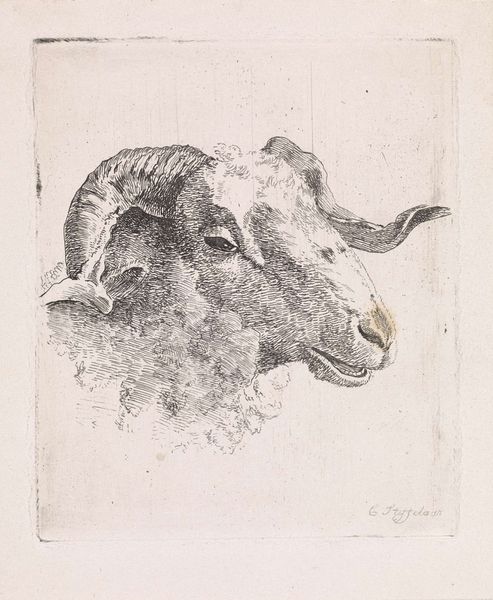

# print

#

etching

#

etching

Dimensions: height 44 mm, width 42 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this artwork, I feel a strange mix of curiosity and discomfort. It's stark, almost unnerving. Editor: Well, let’s contextualize that feeling. We are looking at “Twee geitenkoppen,” or “Two Goats' Heads,” an etching by Abraham Hendrik Winter, likely created sometime between 1815 and 1860. It’s a seemingly simple study, but etchings, particularly during this period, often carried deeper social and symbolic meanings. Curator: Exactly! And given the artist worked within a period grappling with rapid societal shifts—urbanization, industrialization, shifts in agricultural practices—it begs the question, what do goats represent in that moment? Are they stand-ins for something, a critique of the rural poor, a comment on bestiality taboos that often had political resonance? Editor: I appreciate that reading, although, in the absence of more contextual information, one also needs to recognize that artists may choose commonplace imagery simply because it allows them the opportunity to exercise skill and draftsmanship. Winter could simply have been honing his abilities with the etching technique by using readily accessible barnyard subjects. Curator: That said, there’s a undeniable crudeness, or, to put it differently, a brutal honesty in Winter's rendering, particularly of the goat facing us directly. Its expression seems almost confrontational, defiant, challenging any romanticized notions of rural life. We have to wonder how the emerging power structures in this period defined humanity versus bestiality—to think with Derrida, even—who and what has been historically pushed to the margins. Editor: From my perspective, the medium itself -- etching—also speaks volumes about accessibility. Prints allowed images to circulate widely, impacting popular sentiment and influencing perceptions on an unprecedented scale. Curator: That circulation meant this goat image entered existing cultural currents of animal representation, folklore, societal attitudes toward animals... perhaps disrupting, reinforcing, or somehow re-orienting people’s worldviews and values. It is important to also remember that some studies see the etching tradition in Northern Europe with gender; often seen as domestic craft or skill for middle-class women in the nineteenth century. This print allows us to have dialogues around gender and representation too. Editor: I think reflecting on our own emotional response to these goat faces serves a broader purpose. Curator: Definitely! To really ask: how do power structures play a role when we approach non-human and vulnerable beings?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.