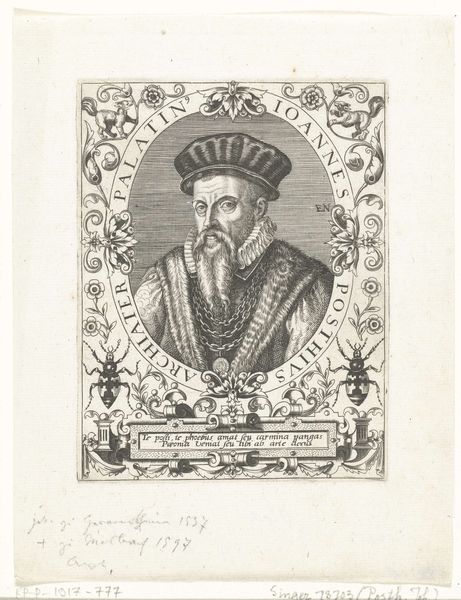

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 123 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

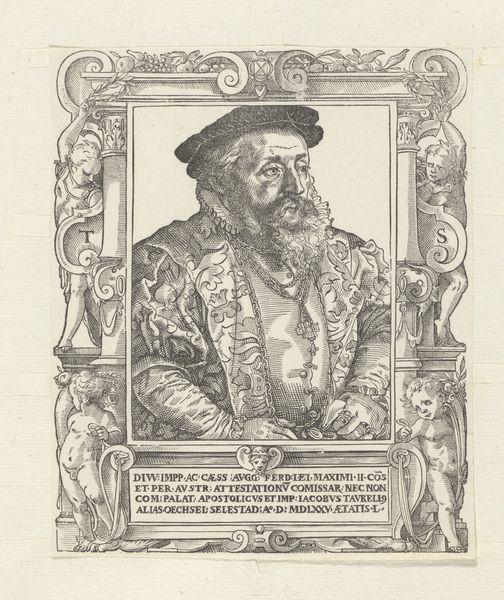

Editor: Here we have an engraving from 1577 titled "Portret van David Burglin in ornamenteel kader" – Portrait of David Burglin in an ornamental frame – made by an anonymous artist. The intricate details create a sense of formality and power. What strikes you when you look at this portrait? Curator: Well, first, the emphasis on David Burglin's social standing is unavoidable. Note the Latin inscription which explicitly describes him. This was intended for a specific audience deeply ingrained in a culture of classical learning and status recognition. How do you see the frame contributing to this message of social status? Editor: I guess the architectural elements – the columns, the figures – they kind of create a sense of grandeur and permanence, like Burglin himself is part of an established order. Curator: Exactly! It's also crucial to note the socio-political climate of the time. Renaissance portraiture served to legitimize authority, power, and lineage. Prints, such as this one, became more widely available, further shaping public perception and contributing to the construction of celebrity and reputation, even in localized settings. Why do you think portraits such as these became increasingly popular at the time? Editor: I suppose with the rise of humanism and the focus on the individual, people wanted to immortalize themselves and their accomplishments. Plus, printed images would allow for wider dissemination of power. Curator: Precisely. So, considering the historical context and the visual cues, how would you now describe this portrait's function beyond mere likeness? Editor: I see it now less as just a depiction and more as an active assertion of Burglin's place within a specific social and political structure. It's not just a portrait, it's a statement. Curator: Indeed! The study of art history reminds us that artworks don’t exist in a vacuum. By understanding the world in which they were made, we can decode the messages that they communicate, intended or unintended. Editor: I definitely learned so much more looking at the world around the work, rather than just the image itself. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.