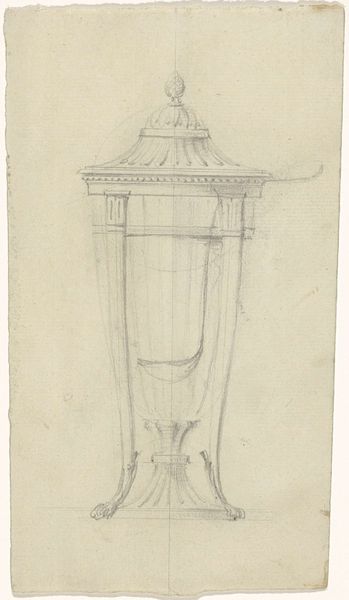

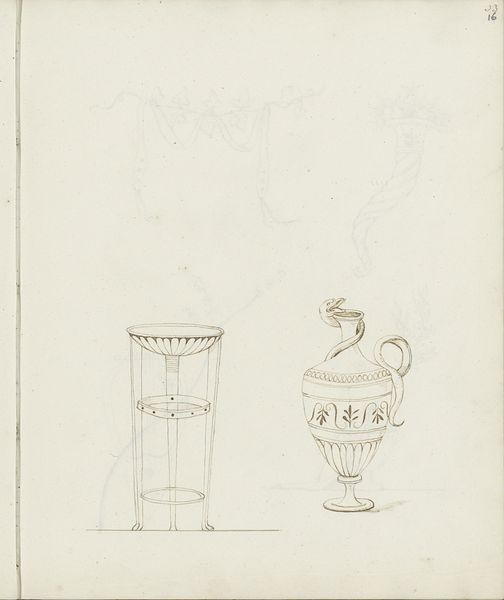

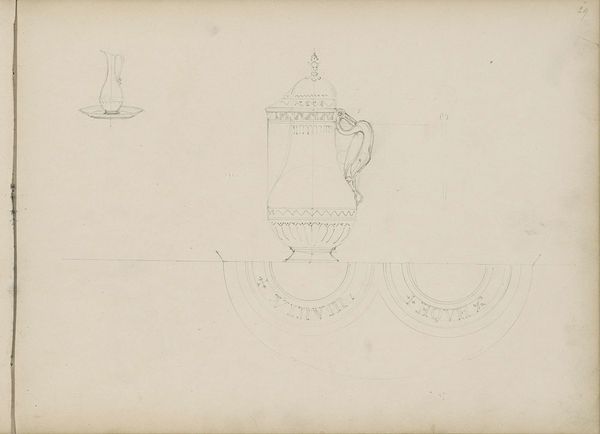

drawing, pencil

#

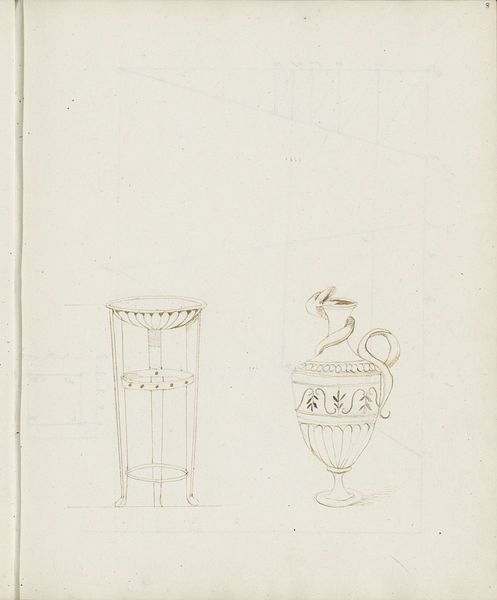

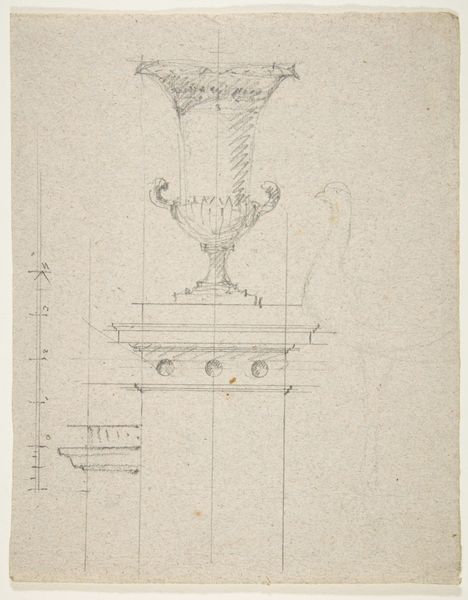

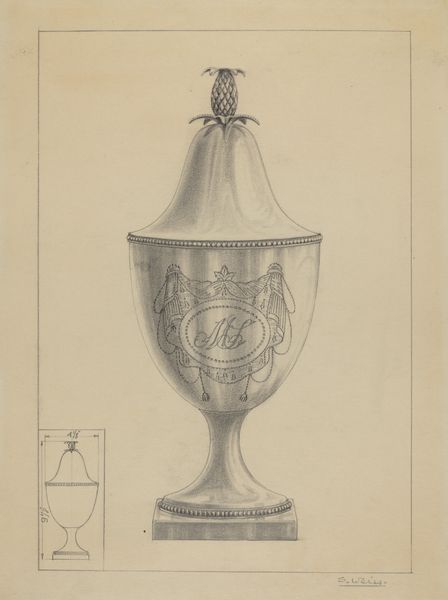

drawing

#

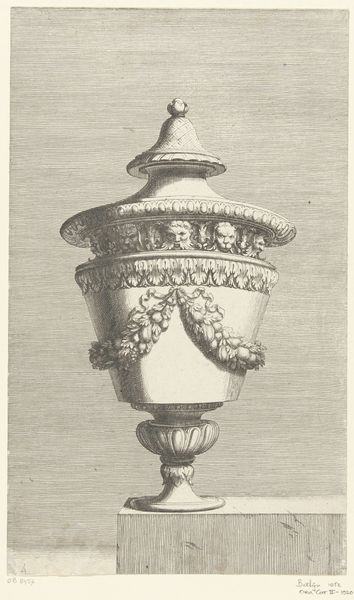

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

form

#

pencil

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 225 mm, width 127 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us we have, "Ontwerp voor een mosterdpot", a design for a mustard pot, rendered around 1780 to 1790 by Luigi Valadier. Editor: It's remarkably restrained for something that's supposed to hold...mustard. It has this subdued, almost academic quality about it. I find the delicate pencil work surprisingly moving. Curator: It is Neoclassical, after all. Restraint, balance, proportion—hallmarks of the age of reason imposed on even the most mundane objects. Valadier operated in Rome, during a time when the rediscovery of antiquity fueled a craze for classical forms. Editor: Look at the visible construction lines, though. This isn't just about aestheticizing power structures. The artist is openly displaying process and tools. I am struck by the interplay between the intended final product, most likely silver or porcelain, and this very unassuming medium—a pencil sketch on paper. Curator: The drawing provides insight into the world of luxury production, and the role designers played in shaping elite tastes and projecting status. Think of it in context, disseminated as patterns and ideas. Editor: Right, these designs acted as currency within craft networks. The subtle details, like the festoon drapery, demonstrate the designer's skill while simultaneously dictating the laborer's activity, as they tried to accurately copy the designs. How does that influence your interpretation of "value" as we look at it today? Curator: The history and taste around certain kinds of objects tell us more about how art is used in culture to indicate societal roles than we could see if this design weren't presented to the public, rather than hidden away for a craftsmen's private consumption. Editor: It pushes us to see both the ideal and the practice, not as oppositional but mutually reinforcing, always reliant on materials. The design elevates labor as part of art, which, frankly, gives more flavor than the mustard inside could offer. Curator: Perhaps its real value lies not just in the object it prefigures but in the insight it gives us into 18th-century design, taste, and social order. Editor: A perfect example of how art conceals and reveals the mechanisms of both its creation and its class implications, simultaneously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.