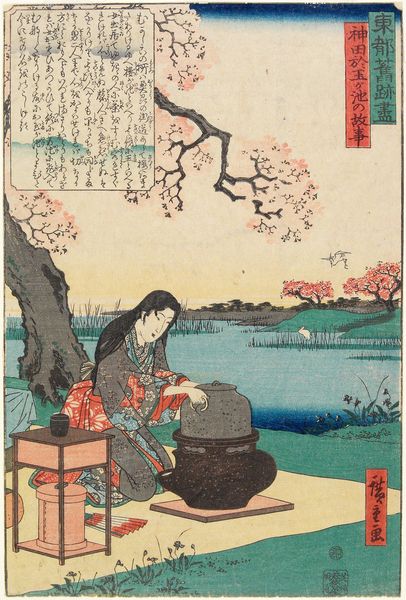

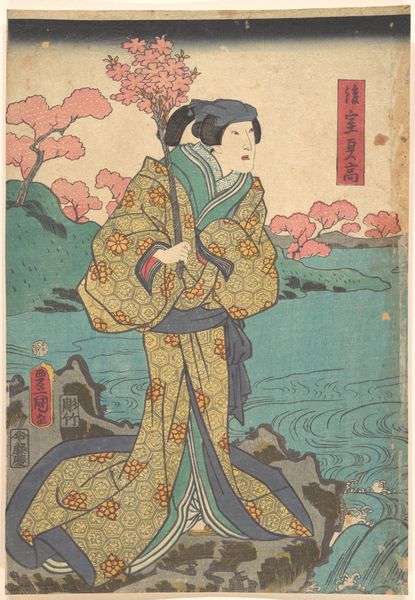

print, ink, woodblock-print

# print

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 14 x 9 3/16 in. (35.5 x 23.3 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Utagawa Hiroshige's "Old Story of the Otama Pond in Kanda," a woodblock print from the 1840s currently residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: My initial impression is one of serenity. The muted colors, the lone figure by the water... It’s a scene of quiet contemplation. Curator: It’s fascinating to consider the process of ukiyo-e prints. Multiple blocks of wood would each be carved and inked separately to create this range of color and depth. How does understanding the labour involved change our perception? Editor: It contextualizes the work within the broader social landscape. This image would have been widely reproduced, making art accessible. Was this idealized vision of nature available to everyone, or was it consumed more by specific social classes? The labor involved would largely fall on craftspeople with restricted status in the era. Curator: Precisely! And the materials, too—paper, ink, wood, all sourced, processed, distributed. We must also think about what kinds of labor were being outsourced in Japan's interaction with the West at the time. Editor: Looking at the central figure, what can we interpret from her positioning in the landscape? The blossoming cherry tree, her clothing, and the act of preparing tea contribute to our interpretation of Japanese femininity in the 19th century. But whose interpretation, really? What assumptions are baked into the visual codes for “femininity?" How might class or lived experience shift this depiction? Curator: Her gesture, leaning over the pot, implies the labor of producing a cup of tea and caring for one's guests. I can almost feel the textures, like the coarse clay of that pot contrasted with the delicate blossom petals above her. The labor to mine and fire those materials is easy to ignore at a distance. Editor: Indeed, so many layers of social meaning tied into something as seemingly simple as tea preparation. We shouldn't forget the power of prints to shape and disseminate narratives. What were these stories, and whom did they serve? Curator: I'll certainly think about the consumption and circulation of prints, the work involved, and what processes can go unobserved the next time I come across a beautiful woodblock. Editor: Absolutely. Understanding how art functions as a form of visual storytelling is always vital, and images like this give us clues into what was seen, and therefore valued.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.