drawing, print, textile, paper

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

textile

#

paper

#

calligraphy

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

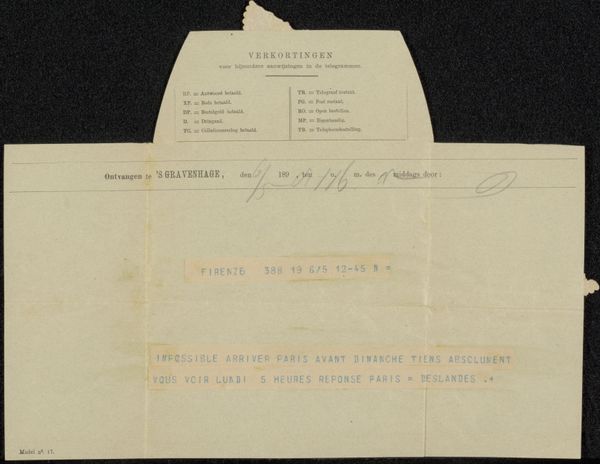

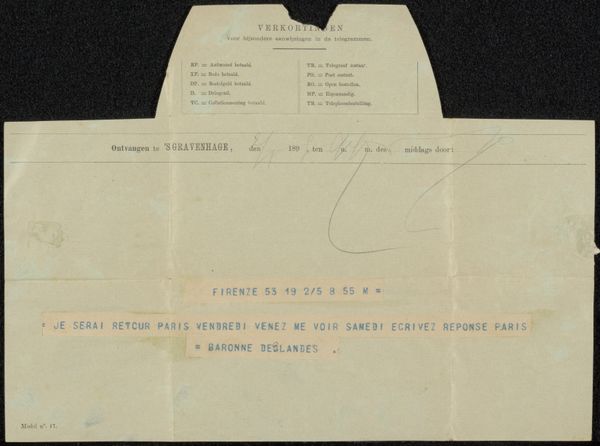

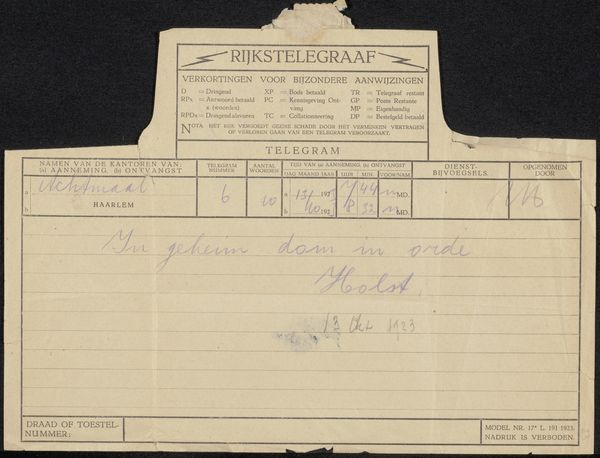

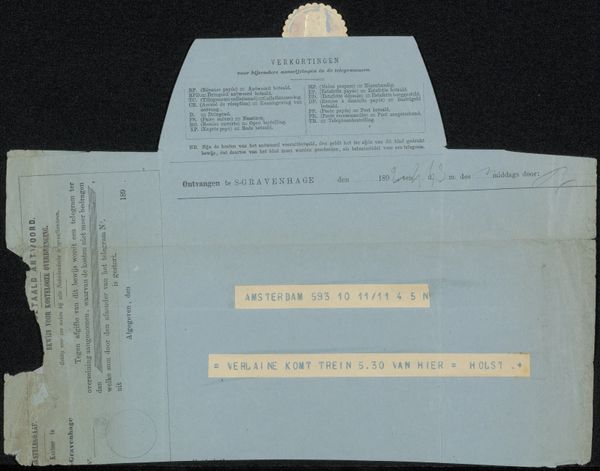

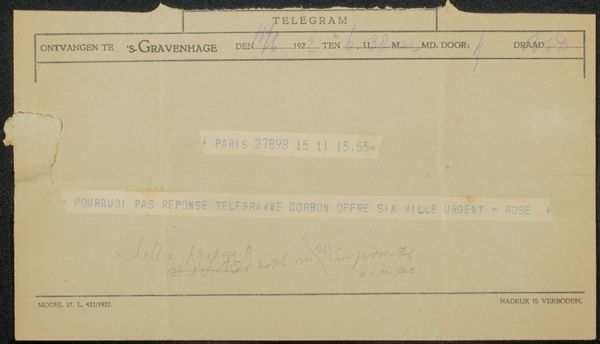

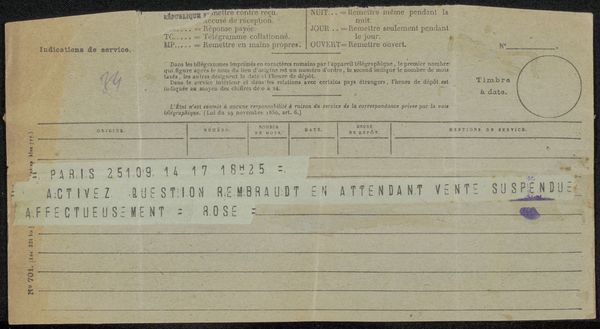

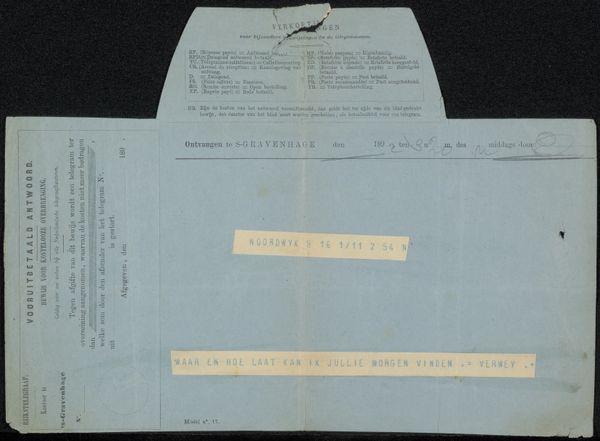

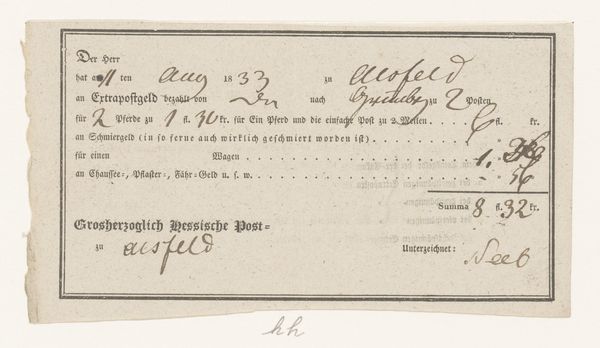

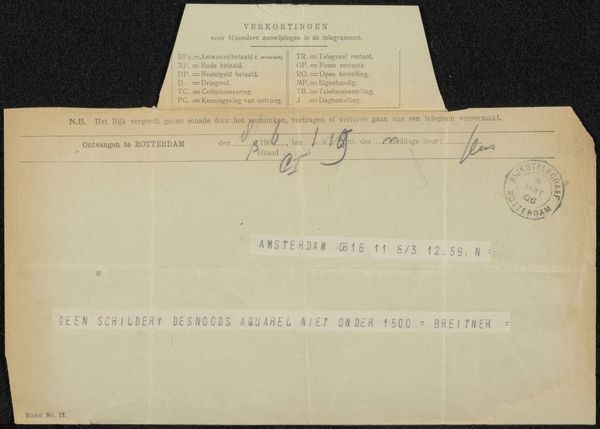

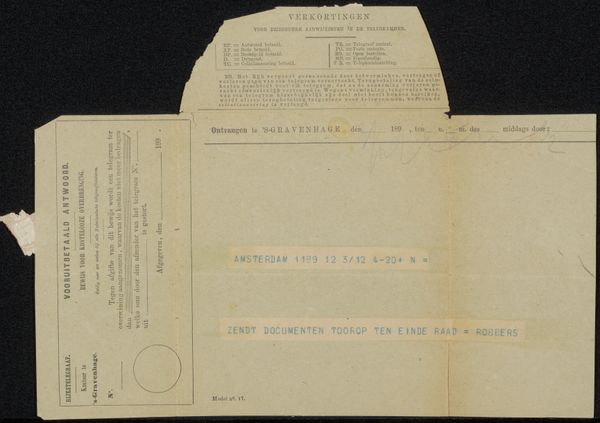

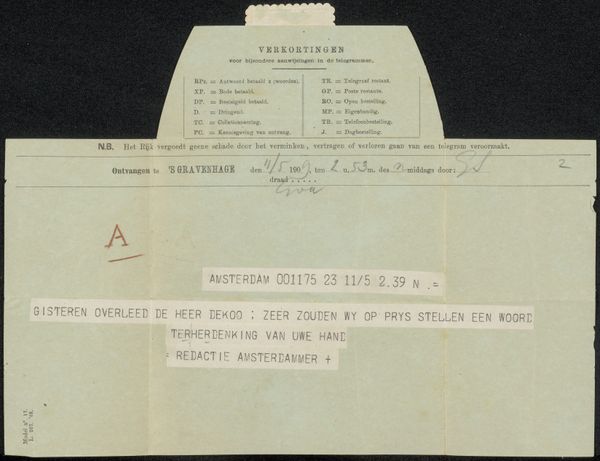

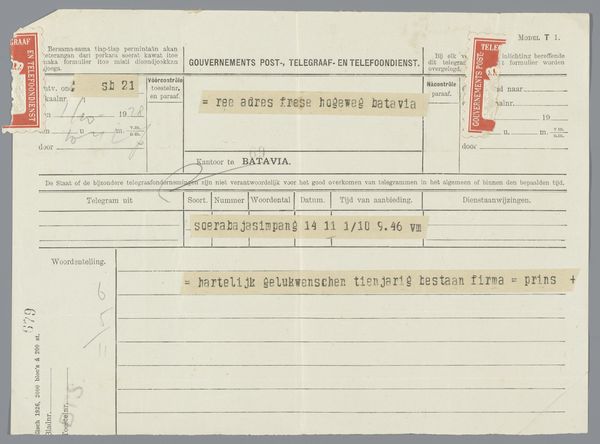

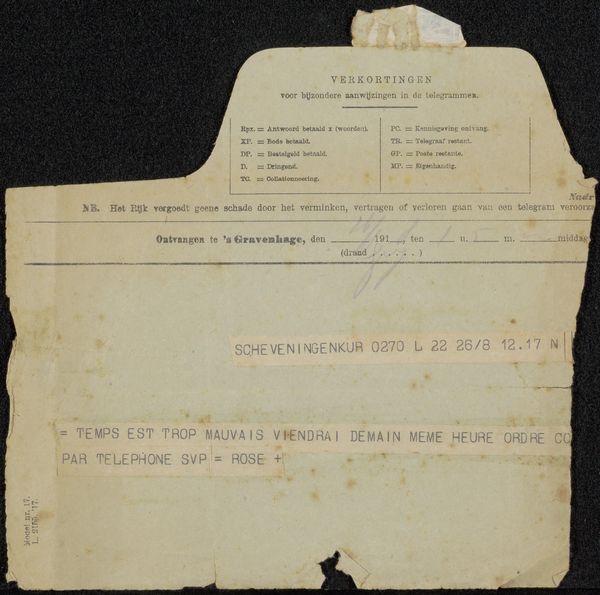

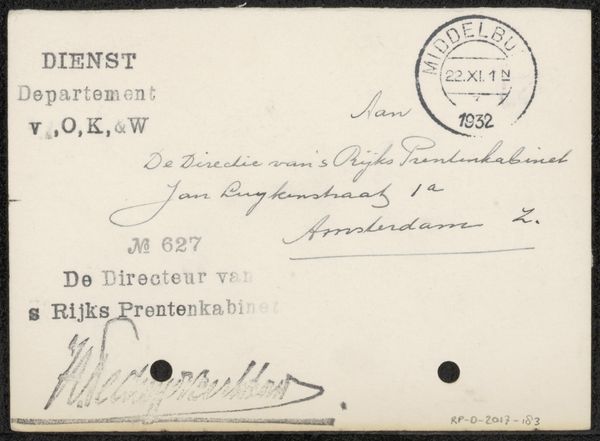

Editor: We're looking at "Telegram aan Willem Bogtman," possibly from 1922, by Richard Nicolaüs Roland Holst. It’s a paper telegram, with handwriting and printed text. It feels almost…fragile, a whisper from the past. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a powerful artifact that speaks to the intersection of art and communication during a pivotal period. The telegram, a rapid form of correspondence in its time, embodies urgency. Holst, known for his socialist ideals, likely understood the inherent class implications of telegrams. Who had access to this technology? What does its use by an artist like Holst, sending a message about "both windows can be placed," suggest about artistic patronage and production in the early 20th century? Editor: So it’s not just a simple message, but also a commentary on society? Curator: Precisely. Consider the tension between the official, bureaucratic language of the "Rijkstelegraaf," and Holst’s personal message. What’s implied? The telegram format itself is part of the artwork's message. Were artists during this period co-opting technologies for art-making or maybe the recipient was commissioning windows in their house? And what’s at stake if we do not preserve a work with a material like paper, in relationship to the original urgency of its message? Editor: I never thought about it that way. It's like the medium itself becomes a statement. Curator: Absolutely. It challenges us to consider how technology shapes not just artistic expression but also societal structures. It begs questions of privilege, access, and the democratizing potential of art, don’t you think? Editor: I do. I’ll never look at a telegram the same way again. This really puts art history into a whole new light. Curator: Agreed. Seeing art as embedded within these complex networks is critical.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.