Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

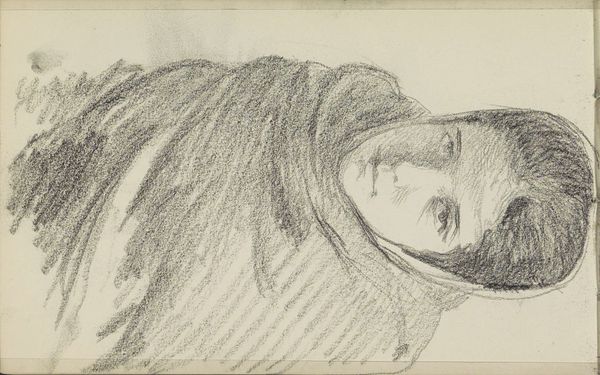

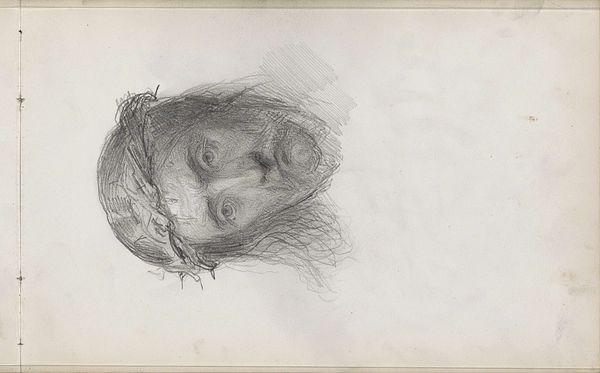

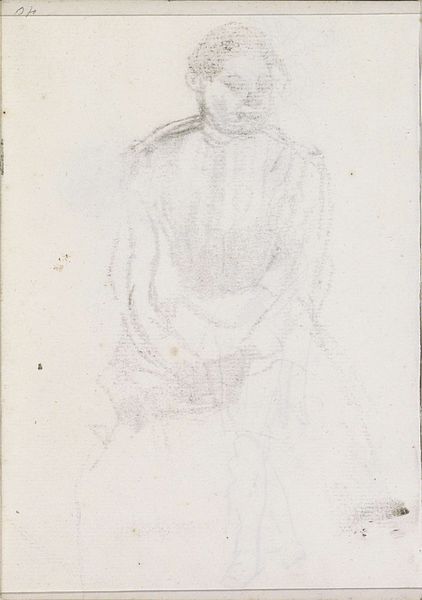

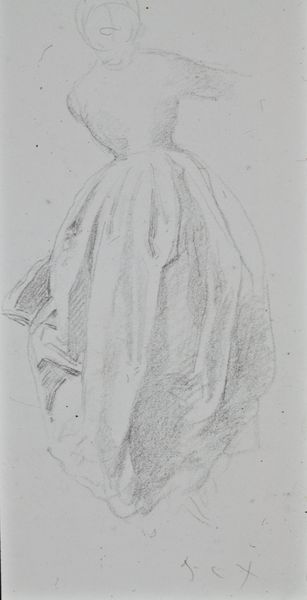

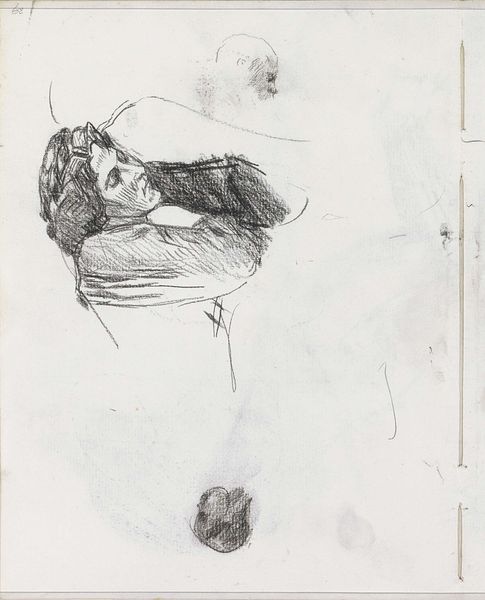

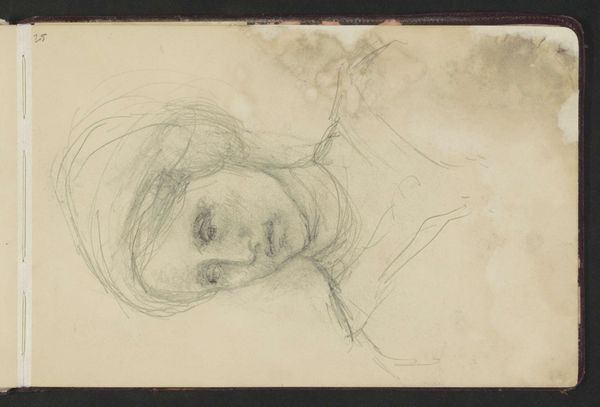

Curator: Before us is "Unfinished Sketch of Lady Haden," a pencil drawing created around 1895 by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. What's your immediate impression of it? Editor: Melancholy, I think. It feels almost spectral. The lines are so light, so ephemeral. It's like a memory fading on the page. Did Whistler usually work in this medium? Curator: While Whistler is best known for his paintings and etchings, this drawing is an exquisite example of his work with pencil. His connection to the subject—Lady Haden— adds a layer of depth. Whistler and Haden were related by marriage and, well, things were complicated. Haden publicly criticized Whistler’s painting style. Editor: So, a familial conflict, perhaps some artistic tension there? Could this unfinished nature speak to the fraught relationship? Maybe he lost interest, or maybe felt a bit conflicted about capturing her likeness. Curator: That's a compelling reading. It makes you wonder about the intent, doesn't it? Why stop here? The unfinished nature can also invite the viewer to complete the work in their imagination, to engage in a dialogue with the artist, even with Lady Haden herself. Editor: It definitely does. It feels like she's about to speak, to offer some bit of wisdom from behind those sketched lines. There's an incredible sense of intimacy, almost as if you're peering into a private moment. The way the soft pencil lines capture the delicate features—it's tender and insightful, particularly knowing their relationship may not have been the most harmonious. Curator: That intimacy highlights the complexities within portraiture itself. Is it about objective representation or something deeper—the portrayal of character, of emotion? Especially within Victorian society. Editor: Exactly. What secrets do you think Lady Haden held? Whistler captures her stillness in such a vulnerable light; it is haunting in a beautiful way. I could sit here contemplating her story for hours. Curator: And it's through these questions, through this contemplation, that the art truly comes alive. It encourages us to investigate the narrative, the nuances, and the intricate layers that shape art history. Editor: And in a way, our own stories, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.