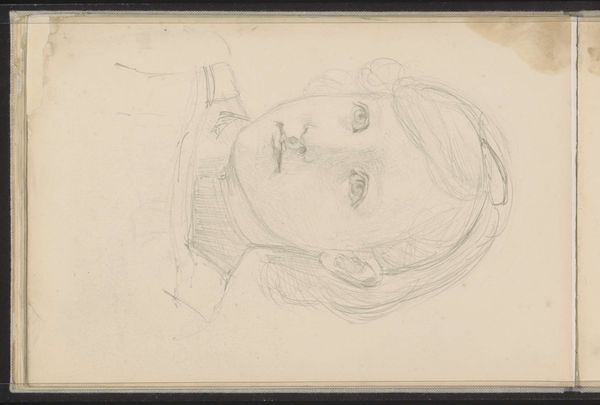

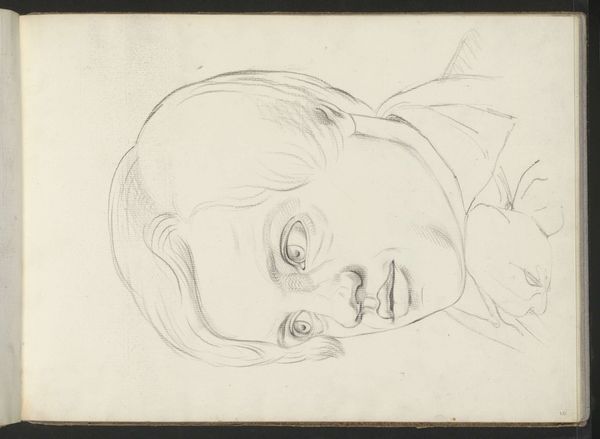

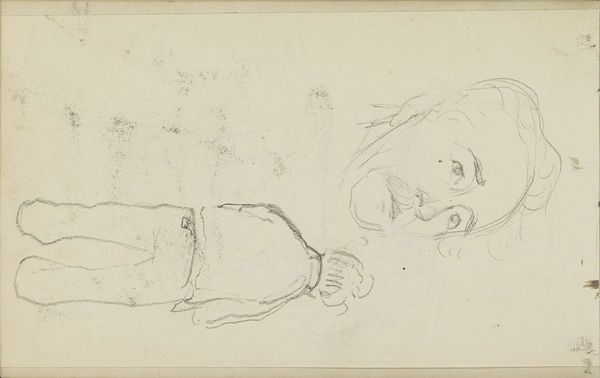

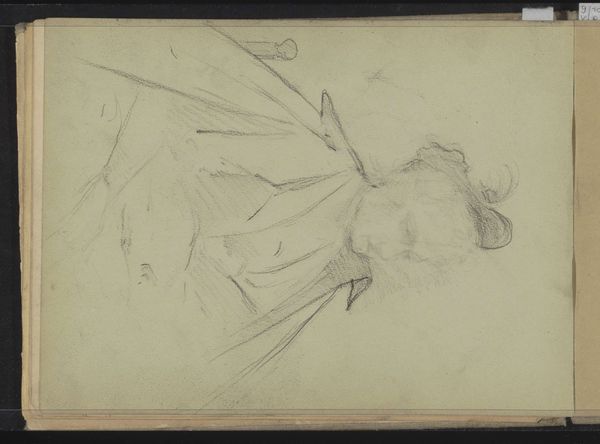

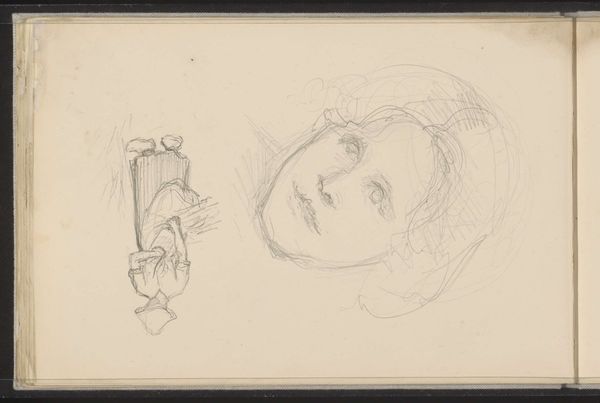

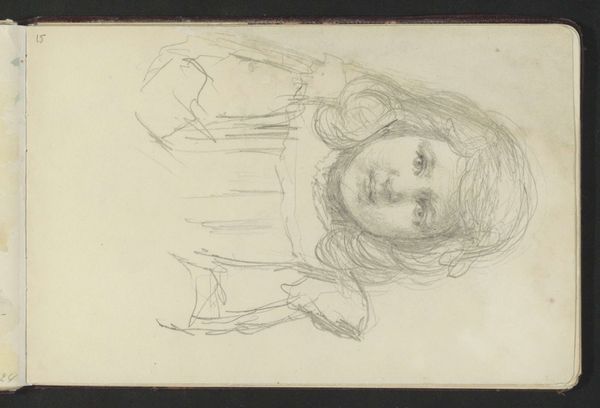

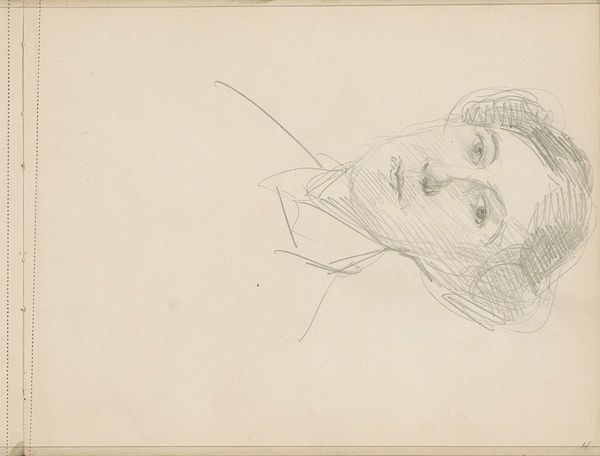

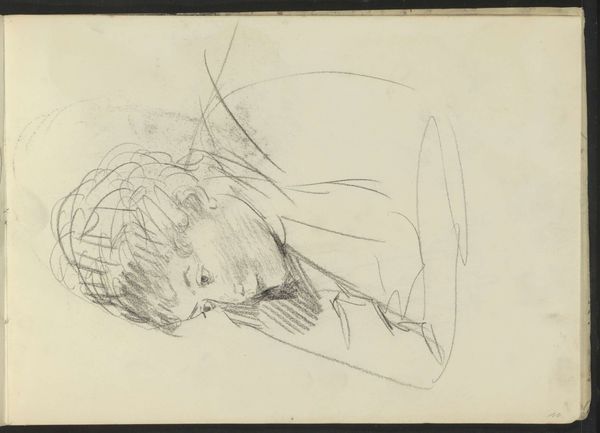

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

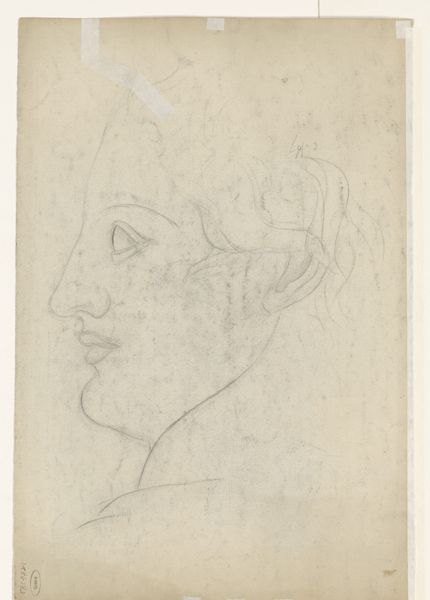

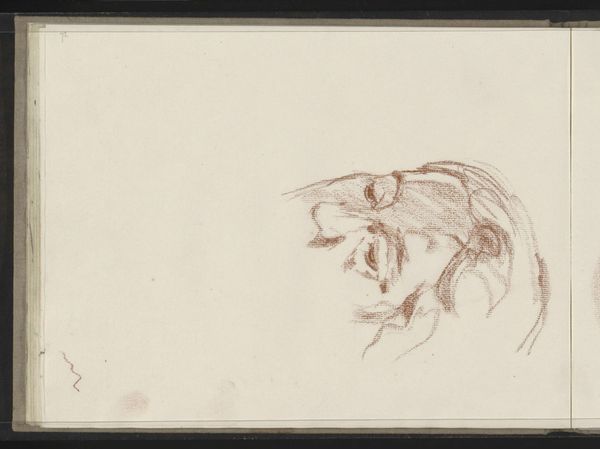

Curator: Welcome. Before us we have “Meisjeskop,” or “Head of a Girl,” a pencil drawing on paper created by Jozef Israëls sometime between 1834 and 1911. Editor: There's an arresting directness to this sketch. Her eyes, wide and a little unfocused, create an almost unsettling sense of intimacy with the viewer. It has a quiet, almost melancholic mood. Curator: It's interesting to consider Israëls’ approach to materials here. The quick, almost hesitant pencil strokes reveal the process itself. We're seeing not just a finished portrait but also the very act of its creation. This immediacy was undoubtedly valued at the time. Editor: And looking at the social context, this piece invites consideration of gender and childhood within 19th-century Dutch society. The girl’s apparent innocence and vulnerability – captured so candidly – might reflect societal views about female fragility. Was it a depiction, perhaps romanticized, of purity? Curator: The loose lines also hint at Israëls’ broader involvement in the Hague School, an artistic movement focused on realism and scenes of everyday life. Was this study part of a larger project focused on depicting working-class families and individuals? This could elevate those previously invisible lives to the canvas. Editor: Indeed. Given Israëls' focus on Jewish life and subjects of poverty, it’s difficult not to read her gaze through the lens of vulnerability experienced by marginalized communities in that era. How does the artwork make visible certain power dynamics? Does her slightly tilted head function as passive surrender, or something else? Curator: Those are compelling observations! Understanding the availability of materials also offers insights. Pencil and paper were easily accessible, which allowed artists a new type of portability and quick study; this contrasts greatly with more laborious mediums such as oils or even bronze sculpture. Perhaps this drawing existed only as preparation for a final piece rendered in oil paint on canvas. Editor: It’s equally important to ponder upon these drawings not just as preparatory studies but also as art objects in their own right. We're left to question their emotional resonance independent of function, to acknowledge the girl as a singular, sentient subject worthy of empathy, or outrage, regardless of completion or polish. Curator: That’s a key point to reflect on, ultimately. Examining the materials and modes of production leads us back to consider how it represents individuals within complex power structures and social milieus. Editor: Absolutely. And thinking about who had access to create, display, or collect images like these prompts us to question established historical canons and consider inclusivity more consciously.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.