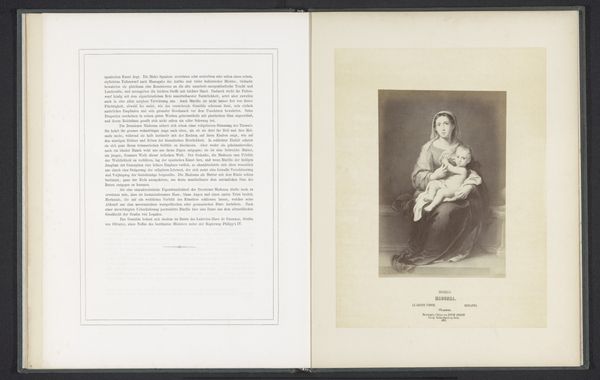

print, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

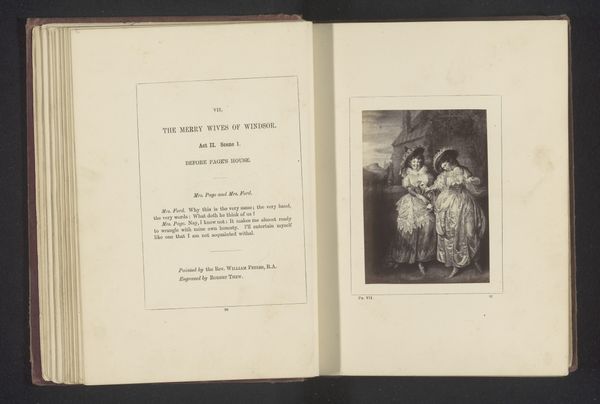

# print

#

photography

#

child

#

academic-art

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 94 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a print titled "Fotoreproductie van La soeur aînée door Adolphe Williams Bouguereau," dating from before 1883. It seems to be a photographic reproduction of a painting, depicting two young girls. I find the image quite sweet and sentimental, what's your take on this image? Curator: The sentimentality is precisely what Bouguereau was selling. But looking at it historically, these images weren’t just about domestic bliss. Consider the rise of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century and their aspiration toward established moral codes and societal expectations. The cult of domesticity idealized the mother, the family and home as places of warmth. How do images like this serve those broader social trends? Editor: So, you’re saying the sweetness is intentional, but maybe it's more like propaganda in a way? A message about what society *should* be. Curator: Precisely! Academic art like this affirmed bourgeois values but also cemented the roles of women and children within it. The photograph also raises the question of mechanical reproduction – making the art more accessible, spreading those values further. Was this photograph perhaps designed for distribution, as a print in a book? Editor: The print does seem to be part of a larger book, with text on the opposite page. I suppose it shows how art was starting to reach a broader audience than just the wealthy elite. Curator: Exactly. And think about how this contrasts with avant-garde movements that were developing at the same time, movements that challenged these bourgeois norms. Editor: So it becomes more than just a portrait; it's a social artifact reflecting the dominant values of the time. Thank you. Curator: My pleasure. Considering these social implications allows us to see how such art pieces played a dynamic role in shaping cultural attitudes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.