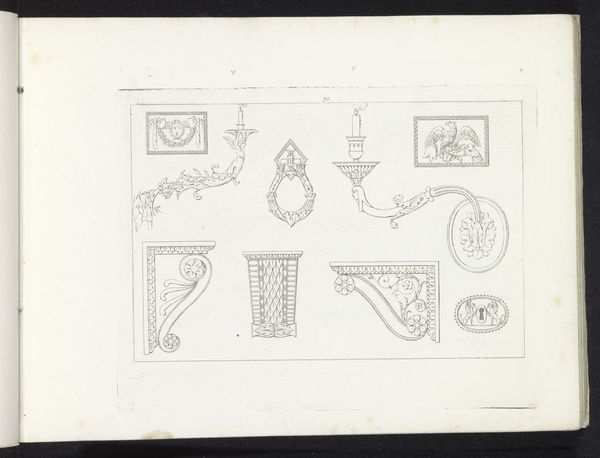

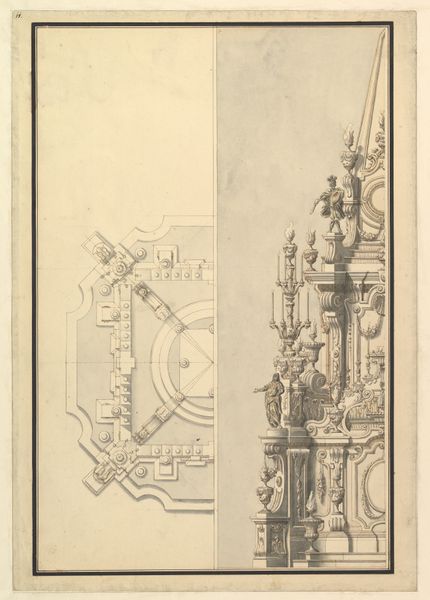

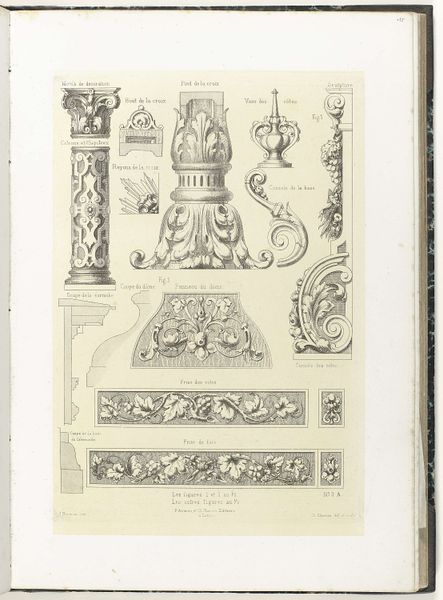

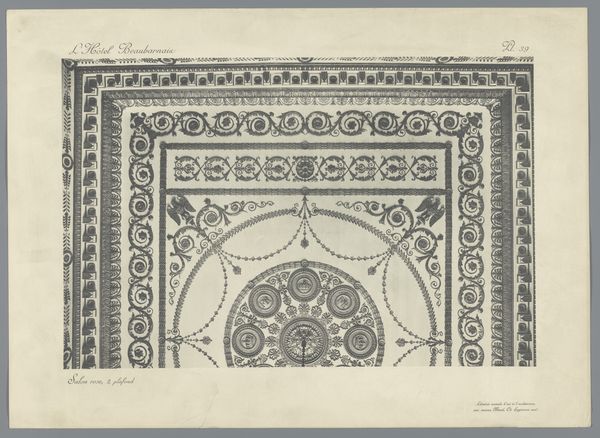

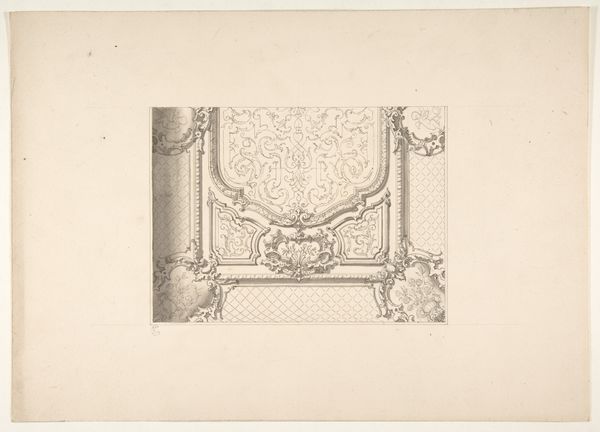

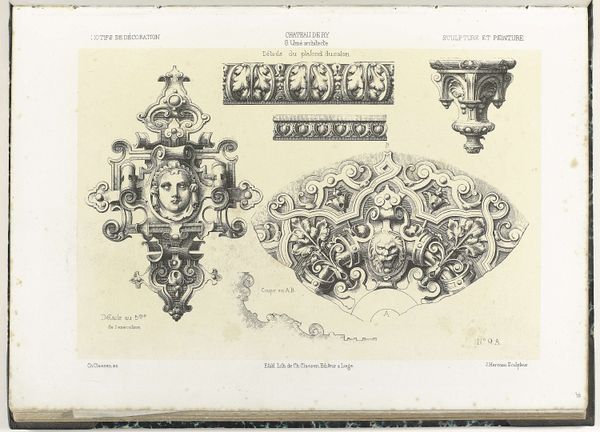

Overzicht van verschillende decoratieve elementen uit de eetzaal zoals kandelaars 1875 - 1930

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 323 mm, width 448 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

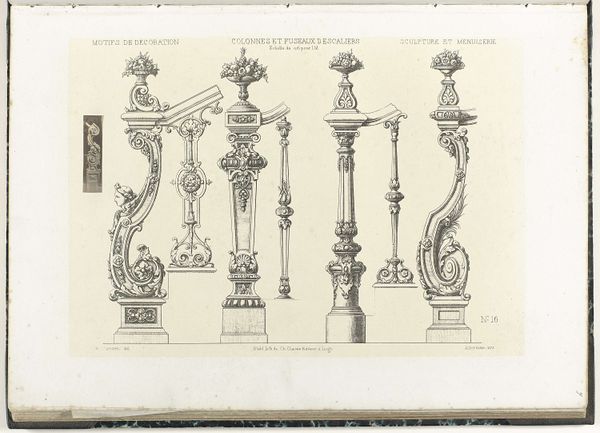

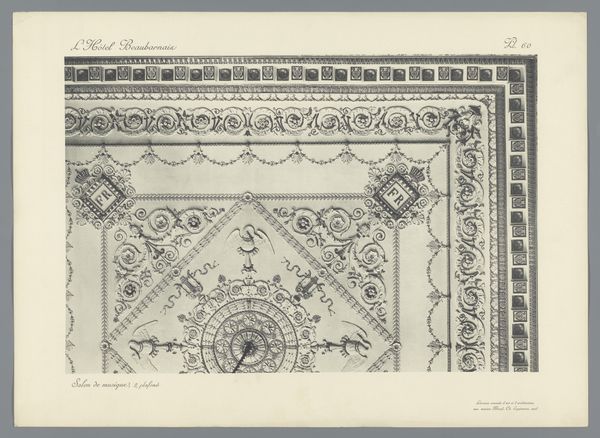

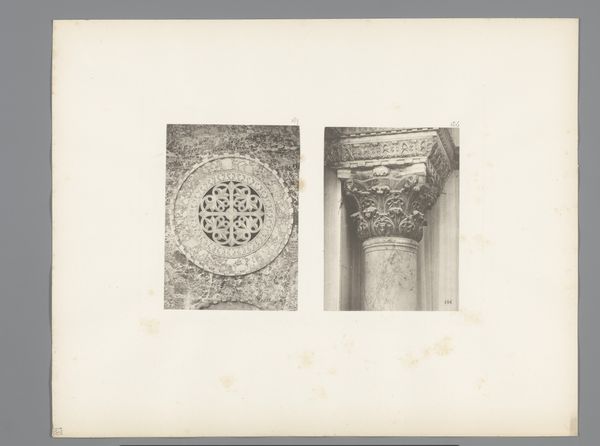

Curator: This print, dating from somewhere between 1875 and 1930, offers "Overzicht van verschillende decoratieve elementen uit de eetzaal zoals kandelaars"—an overview of various decorative elements from a dining room, such as chandeliers. It’s rendered in detailed line work. What strikes you initially? Editor: A pervasive sense of historical excess, particularly conveyed through the symmetry. Look at that elaborate archway detail in the upper left – meticulously patterned with flora motifs. The candelabras feature neoclassical heads, winged adornments, animalistic details—all rendered with intense symmetry and balance. Curator: Yes, balance is a core feature. Consider how the artist organizes the composition—multiple architectural and ornamental fragments laid out for comparative study. We can examine the candelabras as studies in lighting. Note how light would reflect off the metallic surfaces, and the way their placement might activate shadow and texture in the dining hall. Editor: Right. The function of light can signify hierarchy in the social order. The candelabras become powerful emblems of control when you place these design elements inside their social milieu. These aren't merely lighting devices, they perform power relations. Think about the labour conditions and the social strata necessary for the consumption of this gilded-age luxury. Curator: Certainly. Still, focusing strictly on composition, examine the variation across the surface ornamentation. The floral patterns are echoed on the pillars, albeit rendered more geometrically. Or how the column capitals are carved in classical motifs. Do you think these various iterations express hierarchy? Editor: The details illustrate status through ornamentation. However, consider that each emblem, motif, or form in this scene refers to a complex web of subjugation of resources, labour and life itself. We should ask—who benefitted from this meticulously ornamented setting, and at what cost? Curator: The question, in essence, speaks to the power of decorative art: its function is simultaneously to delight and to define. We can continue that inquiry while examining the interplay of symmetry and opulence—and how effectively those formal properties underscore the ideological meanings present in this period. Editor: Exactly. Appreciating these ornate details necessitates recognizing both their intrinsic artistic quality and their role in sustaining historical social orders. This is the paradox we bring with us into this drawing: delight, oppression, history and representation interlinked.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.