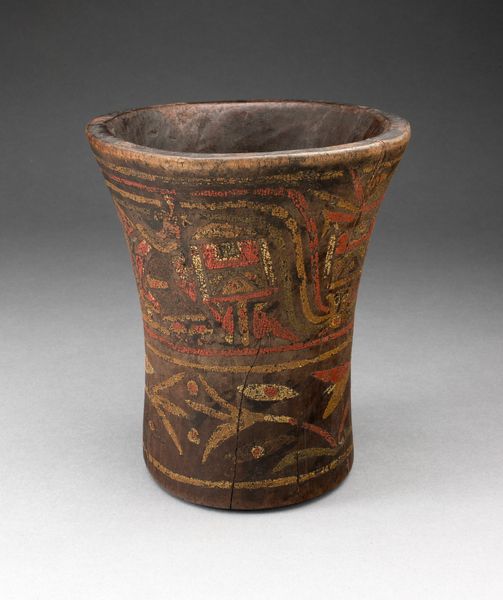

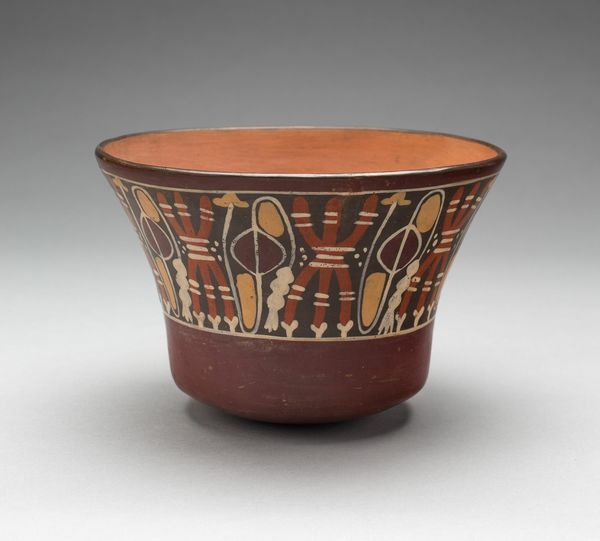

Beaker Depicting Decapitated Heads, Likely Trophy Heads c. 180 - 500

0:00

0:00

ceramic, terracotta

#

ceramic

#

figuration

#

geometric

#

ceramic

#

terracotta

#

indigenous-americas

Dimensions: 14.9 × 14.6 cm (5 7/8 × 5 3/4 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What catches my eye immediately is the striking red and white contrast, which brings a raw, visceral energy to this piece. Editor: Indeed. We’re looking at a ceramic beaker made by the Nazca people, likely sometime between 180 and 500 AD. What we’re seeing depicted here are what are believed to be decapitated heads, probably taken as trophies. Curator: The repetitive geometric motifs, juxtaposed with those graphic, narrative images—heads with faces that appear frozen in shock! It is incredibly unsettling, but so powerful. What's the resonance for you here? Editor: The faces themselves are rendered with an interesting mix of naturalism and abstraction. While recognizably human, they also bear stylized features that transform them into potent symbols. This likely connects with broader Mesoamerican beliefs concerning power, sacrifice, and the cyclical nature of life and death. Notice, too, the geometric elements below – they create a grounding layer, framing the more chaotic figures above. Curator: You're right. That geometric layer contains what appears to be a stepped motif – that visual repetition, particularly combined with the high-contrast, adds to the sense of both ritual and possibly social hierarchy. The Art Institute acquired this piece and it feels representative of a broader colonial narrative, doesn’t it? That ancient object taken far away from its original community and repurposed into museum setting is heavy for a little beaker. Editor: Absolutely. Beyond its intrinsic symbolic value for the Nazca people, this beaker’s current presence in a Western museum like the Art Institute is definitely a loaded subject, speaking to questions of cultural heritage, ownership, and the shifting meanings of objects across time and space. It invites critical contemplation. Curator: It’s fascinating how one small pot can be such a nexus of social dynamics. I look at it, and while my visceral reaction is what hits me first, I end up pondering what exactly we today choose to put on display, and who gets to decide. Editor: I completely agree. These graphic images prompt essential conversations, bridging the past and present. And for me, the strength lies in the emotional, primal impact of that imagery still managing to convey messages even after all this time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.