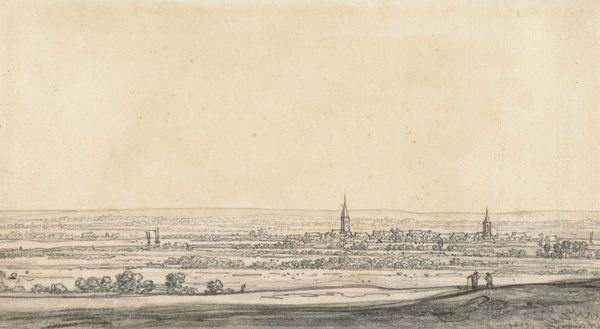

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this delicate rendering of a distant cityscape, one almost forgets how politically charged landscape imagery was during the Dutch Golden Age. Aelbert Cuyp, likely sometime between 1630 and 1691, captured this panoramic view of Kleef using pencil. Editor: The hazy atmosphere gives it such a removed feeling, almost as if you're observing a miniature world. The pencil work is incredible, so fine and yet descriptive. I'm immediately drawn to the details he manages to render, especially with that tonal range. Curator: Indeed, drawings like these provided more than just visual pleasure; they were crucial in establishing Dutch identity and solidifying claims over territory, projecting an image of cultivated land and civic pride to an increasingly engaged public audience for imagery. The very act of representing the land was an act of asserting control. Editor: You see, I am curious as to where Cuyp sourced his materials. What type of pencils were they, who made them? Because of the specificity of line, they must be crafted and of good quality, revealing complex economies behind this seemingly straightforward depiction. And what did it mean for an artist to be investing time and skill in something as quotidian as pencil drawing during a period marked by new painting innovations? Curator: Fascinating points! It’s easy to overlook the networks of craftsmanship, especially when thinking about the final image circulating in a gallery context as part of artistic "high society". The imagery reflects back to this upper echelons, a reminder of property, social stratification, even. Editor: And those lines aren't just lines, they signify labor, access to resources. Even this perceived effortless atmospheric effect—was this achieved with particular pigments incorporated into the drawing tools? Curator: Considering how art became increasingly intertwined with the growing merchant class, drawings such as this provide us insight into social status and the relationship with landscape as something both aesthetic and economic. Editor: It truly demonstrates how every material detail of the piece, including its production and the labor that sustains the scene it depicts, tells us much more about the place of image production in a society. Curator: A poignant reminder that viewing landscape, and really any image from this historical context, means reading a detailed network of cultural and material meaning. Editor: Yes, and a reminder that even the seemingly simple is entangled with layers of practice, labor, and means of material engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.