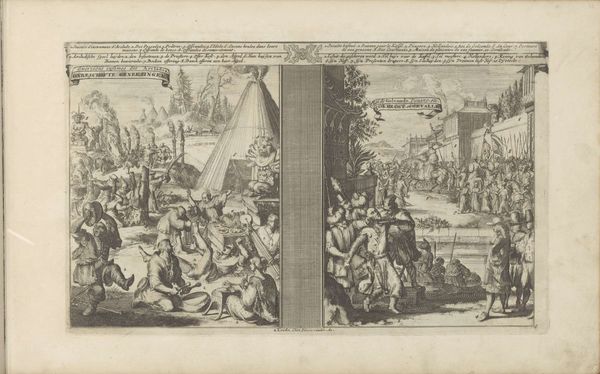

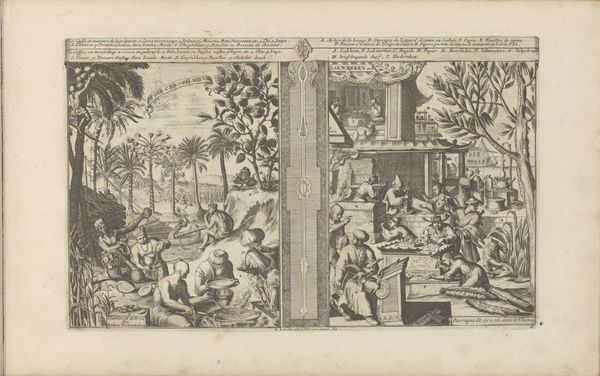

Hof van de Tartaarse keizer; Braziliaanse Tapoeiers bereiden hun voedsel 1682 - 1733

0:00

0:00

romeyndehooghe

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

orientalism

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 339 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

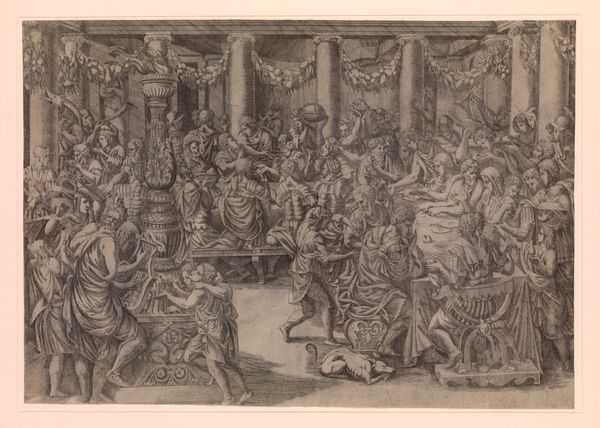

Curator: This print, dating from between 1682 and 1733, is titled "Hof van de Tartaarse keizer; Braziliaanse Tapoeiers bereiden hun voedsel", or "Court of the Tartar Emperor; Brazilian Tapuias Preparing Food", and it comes to us from the hand of Romeyn de Hooghe. The printmaking medium used here is engraving. Editor: Oh, this is striking! I'm immediately drawn to the sharp contrast, visually, and then how…jarring the two halves feel when juxtaposed. A sumptuous court on one side, and what appears to be, well, a scene of Indigenous life, maybe slightly caricatured, on the other? It makes me instantly wonder about power dynamics. Curator: Indeed, the division is quite deliberate. De Hooghe crafted this as a commentary on cultural difference, playing on European fascination with the exotic. The "Tartar Court" section would have resonated with the contemporary interest in far-off lands and rulers, while the Brazilian scene—depicting the Tapuias— catered to the burgeoning market for ethnographic imagery. Editor: I find myself lingering over the faces. The Emperor’s court seems quite still and proper, the figures rigidly upright, while the Brazilian Tapuias preparing their meals have dynamism to them. Is this deliberate do you think? Is De Hooghe trying to tell us more with their placement? Curator: That’s a very perceptive observation! And very possible. It's fascinating how De Hooghe utilizes composition to create a narrative – almost a primitive vs. civilised binary – typical of European perspectives from the period. He certainly frames it in the language of orientalism and othering that's present in a lot of art from this era. The way he depicts clothing, architectural style, the rituals around food preparation… It's all designed to emphasize difference. Editor: Right, I notice how both sections are busy and bustling, but the sense of space and the level of implied violence set very different moods, which are in turn a sharp critique of how Baroque era royalty functioned at the time and their perspective of the colonized. There is also the slight possibility that De Hooghe felt conflicted here – given he was Dutch, he must have felt keenly about colonialism versus supporting the lives and values of the Brazilian Tapuias? Curator: A really astute point to bring up: conflict. Perhaps not internal so much for De Hooghe himself but absolutely indicative of broader anxieties playing out in Dutch society at this time! I mean the two panels speak to how the social contract could fracture depending on the location or cultural circumstance, I would suggest. Editor: It's a fascinating window, if an uncomfortable one. Curator: Absolutely, a glimpse not just into how others were seen, but how a culture perceived itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.