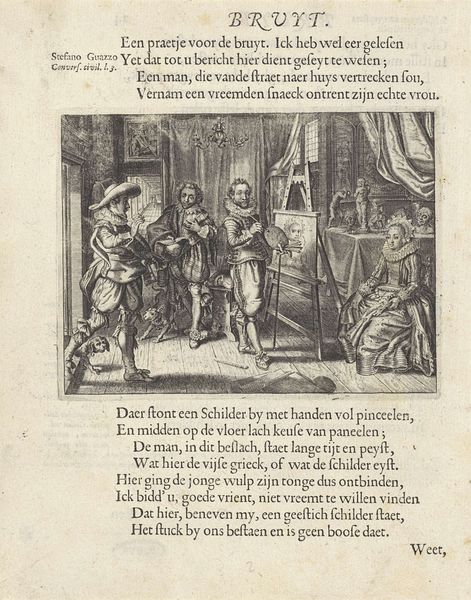

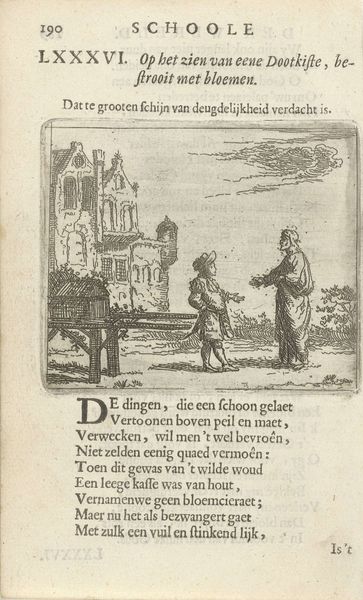

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 88 mm, height 66 mm, width 82 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

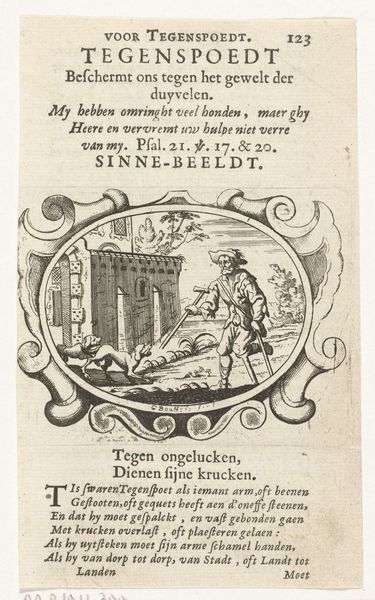

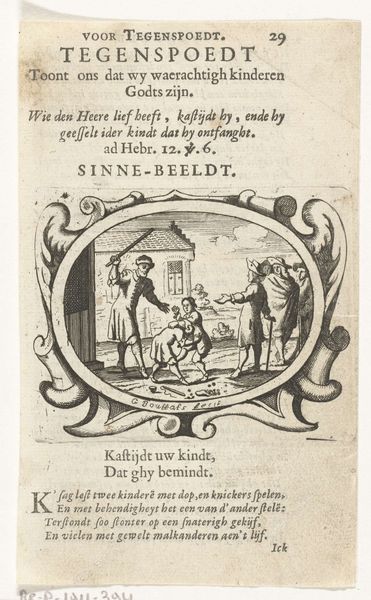

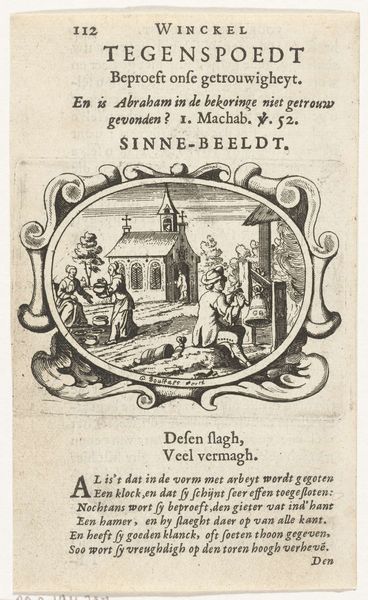

Curator: This is Gaspar Bouttats' engraving from 1679, "Tegenspoed wordt gezonden door God," or "Adversity is sent by God." It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first impression is of stark contrast and carefully delineated space. The frame really draws the eye in to the unsettling scene. Curator: Indeed. Note the balanced composition, bisected horizontally. Below, a packed crowd of spectators frames the main scene, with their gazes, drawing our eyes, toward the central subject matter. Above them is what seems like some sort of justice proceeding, perhaps. The stark contrasts are achieved through the engraving itself, and what we can deduce of its materiality in stark contrast with that dark central scene. Editor: Yes, the density of figures gives an almost claustrophobic sense to the print. The central figures on that scaffolding draw all of my attention: a man being whipped, the punishing officer with the reeds, the crouching figure with what appears to be a branding iron or perhaps cauterizing agent heating in a brazier. The title and accompanying text would suggest that it depicts earthly adversity being dispensed with divine permission? Curator: Precisely. The "SINNE-BEELDT," meaning something akin to emblematic picture, reinforces the message alongside the text. The architectural components further establish the structure of divine intent made physical on earth: Observe the symmetry, the lines repeating as they fade back into the perspectival space—its rigorous lines of organization speak to something like structure of thought itself. Editor: The symbols definitely carry weight. I read it as a commentary on social hierarchy and divine judgment. What's interesting to me is the emotional ambiguity captured within the composition: Do we sympathize with the figure being punished, or are we meant to see it as deserved divine retribution? The expressions on the faces of the figures around would tend toward reinforcing an expectation that such is deserved—social consent toward the justice. Curator: And look at the bordering frame itself. Ovoid, adorned with vegetation—the organic and classical—subscribing to the structures and ideas and forms circulating in Bouttats’ era. The engraving as a totality certainly achieves a synthesis, both visually and conceptually, creating an artwork whose lines work to reinforce the structure itself. Editor: Pondering how historical prints like these shaped understandings of morality and power is rather chilling. It forces us to confront how symbols are never neutral; they carry histories and influence our perceptions—an image is never merely formal, of course.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.