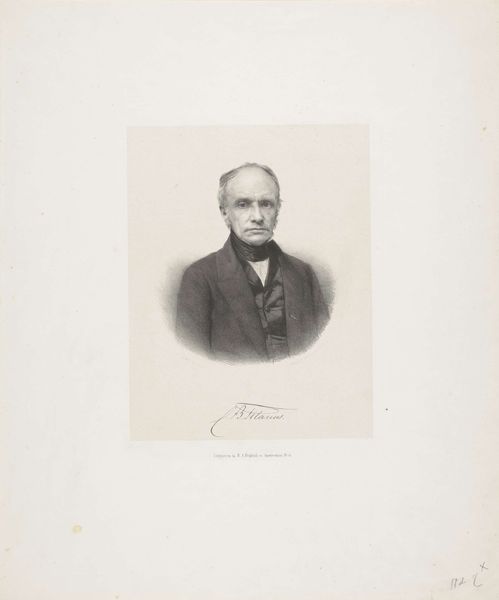

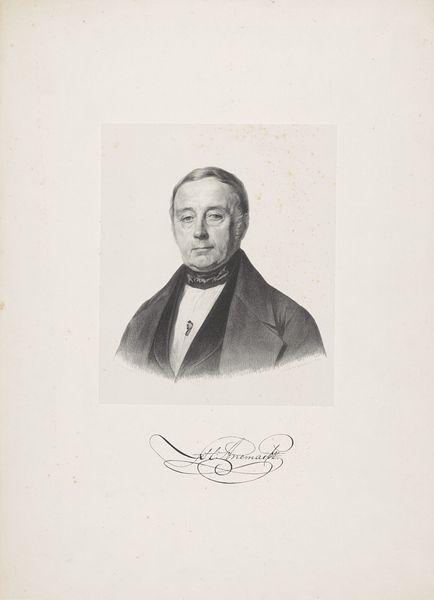

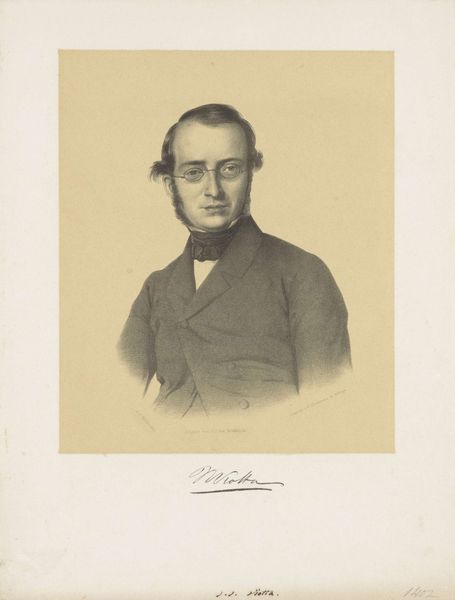

drawing, ink, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

realism

Dimensions: height 298 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re looking at “Portret van Jacques Cuylits,” a pencil drawing currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. The work dates to sometime between 1831 and 1890 and is attributed to Jean Baptiste Pierre Michiels. Editor: It feels… austere. Even with those meticulously rendered textures of the jacket, it’s so restrained. There's a very strong emphasis on the face, but there's something almost withholding in his expression, like he's observing but not revealing. Curator: Exactly. It is realist, but stripped down to its most elemental form. The material presence of the graphite and ink – look closely, it really is exquisite draftsmanship – feels almost like a commentary on the man himself, the way his inner character is translated. Editor: I wonder about the labor that went into this, how the materials themselves – graphite, paper, ink – were sourced and valued. You know, during that era, even the *making* of the materials, let alone the drawing, involved complex social and economic networks. Someone’s livelihood depended on crafting that graphite stick, processing the ink. The whole apparatus of drawing became increasingly mechanized at the end of the 19th century! Curator: It's a portrait intended to last, to solidify an image. Portraits served this critical purpose to remind the people for whom this portrait was intended of his importance. Does it feel lasting to you? Does this feel real in some deep way? I almost get a photographic feel to it, the stillness, do you think Michiels tried to capture more than likeness? Editor: Photography as process had great sway at the time, right? And portraiture democratized rapidly in the 19th C.! In thinking of its production as part of an economy – not a luxury – adds something that is less easily expressed. This era grappled with questions of accessibility in production methods, not only image capturing, where art had typically represented exclusively privileged classes. Curator: Perhaps the essence isn't found *only* in his features, but as much in the social realities in which this image comes to be and finds context. We should, as you propose, value equally not only the image as signifier but what it comes to reveal about his class status as well. Editor: Well, to look beyond the obvious portrait means engaging with an incredibly wide and textured historical landscape—something worth considering! Curator: Exactly! Perhaps one aspect we missed focusing on earlier to expand our appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.