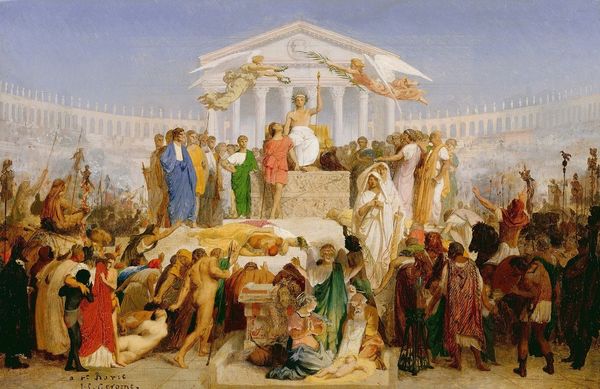

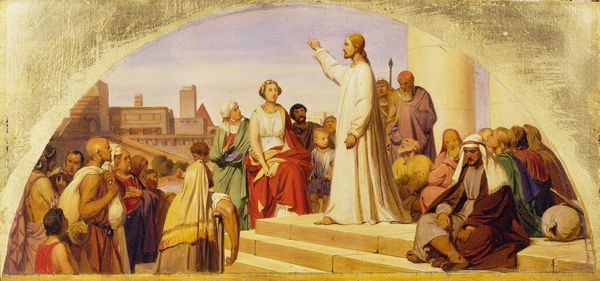

oil-paint

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

roman-mythology

#

classicism

#

mythology

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 386 x 515 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: Ingres’ "The Apotheosis of Homer," painted in 1827, is absolutely packed with figures! The sheer number of portraits is quite striking, creating a somewhat staged, theatrical feel, but there's clearly a story here, could you share your take on the piece? Curator: It's not just *a* story, but the *story* of art history, carefully constructed through materials, labor, and consumption. Look at the oil paint – a costly material at the time, signifying the wealth and patronage necessary for a project of this scale. How does the deliberate crafting of this image of "High Art" actually erase the physical and social conditions of its making? Editor: You mean like, who ground the pigments or prepared the canvas? Curator: Exactly! Consider the implications of depicting Homer enthroned within a classical temple. It’s made of stone, presumably marble; think about the quarrying, the transportation, the sculpting by artisans - all this physical work just to set the scene, and yet these hands are rendered invisible. And furthermore, who is depicted here and who is left out? How are power dynamics reproduced within this scene? Editor: It’s interesting that you point out the social and economic labour needed for its realisation. I was caught up in identifying the various figures! But, if we consider this as an art object produced in 1827, who was it *for*? Curator: A wealthy patron or a government, undoubtedly! Ingres crafted not just an image but a valuable commodity, reaffirming social hierarchies through both the *subject* – the elevation of Homer – and the *object* itself: the grand oil painting itself. Who had access to this kind of art? Editor: Thinking about who had access really shifts the emphasis from individual genius to something far more collaborative, and also unequal... It adds layers of meaning. Curator: Precisely. It reminds us to consider not only *what* is represented, but *how* the very materials and processes of creation contribute to its cultural power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.