Copyright: Public Domain

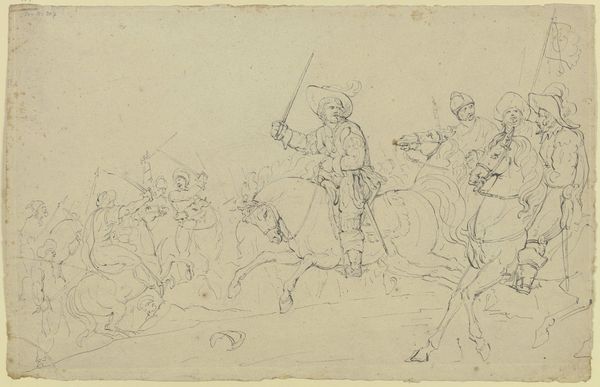

Curator: Georg Philipp Rugendas’s work, “Equestrian Combat,” likely made in 1705 based on the inscription at the lower left, is quite compelling, isn’t it? Editor: It’s chaotic, but controlled. Look at the layering of these quick ink strokes. It definitely gives the impression of the intensity of battle. Curator: Exactly. The application of ink is what immediately catches my eye, because Rugendas uses the line as both form and movement. The rapid, almost frantic, use of line mimics the tumult of warfare. It certainly reads as a scene full of both human and equine dynamism. What draws me in is trying to imagine how works such as these are circulated, perhaps to political actors or publishers during the era of these frequent and violent conflicts across the continent. Editor: Yes, the ink medium does allow for a quick replication. It is certainly reproducible for disseminating imagery tied to social conflicts in early 18th century Europe. Do you think he directly observed warfare firsthand or maybe gleaned imagery of social conflict from popular media? The fact it’s on paper, and not a grand canvas, brings this event to the public on a more intimate level. It’s almost as if he wanted the viewer to understand the brutal process that constitutes these so-called epic struggles. Curator: That's insightful. We should consider the public's hunger for news, imagery, and validation about violent disputes between royal lineages during this period. Editor: Perhaps what fascinates me most is how he renders these dramatic confrontations, these highly material encounters with ink and paper, to address conflicts during the War of Spanish Succession. Curator: Indeed, the baroque era clearly lent itself to such grandiose depictions, even within the constraints of ink drawing on paper. Rugendas appears to skillfully manipulate the relatively immediate nature of ink, with its wide dissemination, for significant historic episodes. Editor: Precisely. In examining the lines, their chaotic dance across the paper, we grasp not just a scene, but a sense of the societal and political quagmire consuming early 18th-century Europe. Curator: Well put. And a sobering reminder that even seemingly simple materials can transmit complex and brutal messages across generations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.