Dimensions: height 91 mm, width 118 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

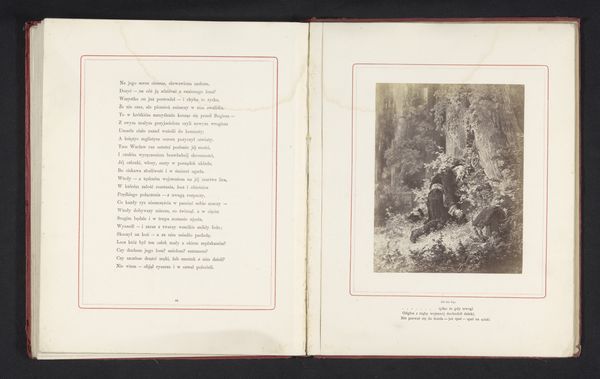

Curator: Here we have a photographic reproduction of a print, dating from before 1876. It’s titled “Fotoreproductie van een prent, voorstellende de val van Satan” which translates to “Photographic reproduction of a print, depicting the fall of Satan”. It looks like it comes from a book? Editor: My initial reaction? Intense. It feels almost claustrophobic, the way the light struggles against the darkness. It evokes a powerful sense of dramatic downfall and despair. Is that Satan, almost swallowed by the shadows? Curator: Precisely. Given the era and the subject matter, it’s safe to assume the source material for this reproduction was deeply influenced by Romanticism. Think about the late 18th and early 19th century. Revolutionaries began questioning existing power structures. They sought deeper meaning and drama in stories about heroes, outcasts and even fallen angels. Editor: Absolutely. You see that dramatic sweep of light; almost like divine condemnation crashing down on him? And yet, he's almost defiant, still grappling even as he falls. It mirrors that revolutionary sentiment you mentioned: resisting established authority, even in the face of inevitable defeat. The original image is tucked next to Milton's *Paradise Lost*; this historical positioning gives insight into understanding the original photographic commission. Curator: Note how photography, still relatively new, is being used to reproduce existing prints, making art accessible to a wider audience. The layered process speaks to how rapidly visual culture was changing. Think of how political cartoons gain a second life. We understand that art isn't passively viewed, its meaning shifts with socio-political and aesthetic tastes of the moment. Editor: It’s almost like a precursor to digital art today; constant reproductions, reposts, reframing. Except this time, a photograph, in itself claiming a space for modernity in 1876, is taking an older print into that contemporary light. The fall of Lucifer, romanticized by both Milton and the printmaker, now further mediated by an anonymous photographer. Curator: Precisely, and in doing so, it opens new avenues for how to read that fall from grace, and all of those different layers from myth to poem to image reflect our constant interpretation and reiteration of past symbols. Editor: So, in the end, even a fall, captured in an old book and through this copy, leaves us with a fresh interpretation about who we are now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.