Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van mensen rond een bed van iemand die ziek is of sterft before 1884

0:00

0:00

print, intaglio, photography

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

# print

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

paper medium

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 199 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

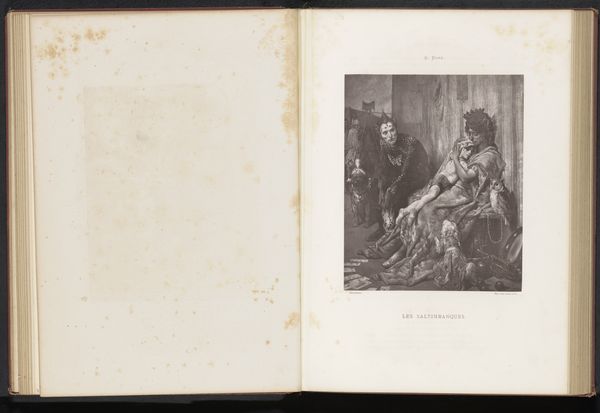

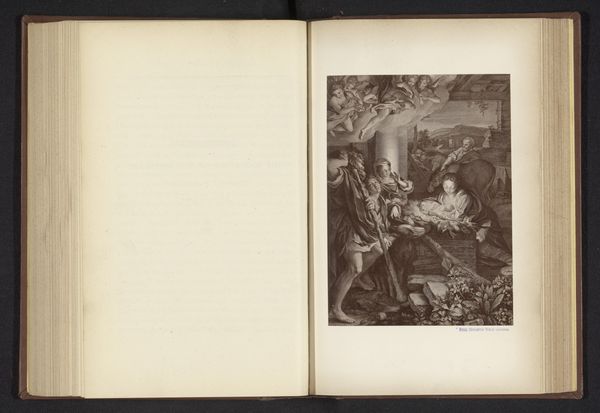

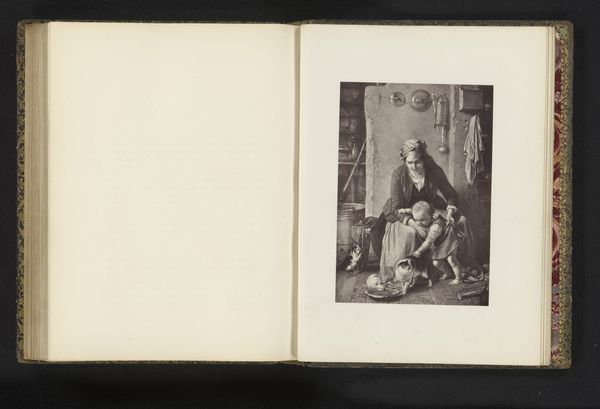

Curator: Here we have "Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van mensen rond een bed van iemand die ziek is of sterft"—a photo reproduction of a painting showing people surrounding the bedside of someone sick or dying—from before 1884. It is an intaglio print on paper. The original artist is, unfortunately, anonymous. Editor: Immediately striking. The gravity is heavy in this scene, everyone seems engulfed in quiet despair. There’s something profoundly intimate yet deeply performative about the grief on display. Curator: Notice how the figures cluster around the bed, drawn to it, but also positioned almost like witnesses to a public event. The visual vocabulary really highlights the societal weight placed upon death and mourning, the ritualised responses to such an event. The child at the foot of the bed almost seems to stand for a symbol of innocence confronted by mortality. Editor: Absolutely, and the academic style lends a sense of historical "truth", a reinforcement of these social scripts around death and illness. Consider the implied power dynamics: the adults towering over the possibly dying figure, embodying established hierarchies of care, gender, and age. There’s also a distinct religious sensibility— Curator: I see what you mean. On the upper right corner is indeed a cross. It emphasizes how death in the past had significant Christian cultural memory encoded in this event, with death a moment of transfiguration or transformation, with significant visual tropes: the mourners, the ill person in the cruciform pose, all point towards that culturally shared script. Editor: But let’s not ignore that child by the bedside again; doesn't it strike you as a stark commentary on inherited trauma and the cyclical nature of suffering through generations? Is the innocence of the youth an indication of some form of new possibilities emerging out of despair? Or that of learned behaviour, a reinforcement of certain belief systems that have dictated behaviour, tradition and hierarchy, over extended periods of time? Curator: You bring up fascinating points about the cultural undercurrents embedded in these visuals. It certainly complicates any simplistic reading of piety. The image offers a somber insight into 19th-century life, while still posing crucial questions relevant today: about the visibility of death, our performative and sincere responses to death, and how those collective experiences define communities and family lineages. Editor: A sobering work, yet one that prompts meaningful dialogues on culture, mortality, and the historical gaze. Curator: Precisely; symbols carry weight. I hope it sparks equally introspective discussions for you, the listener, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.